Someone stole the Whirpletons Cashews last night. Now, during morning vittles, Numb Nuts the former Whirpletons flying squirrel ain’t got a clue what to do. He flings himself off my yellow Stetson and takes to the aerial currents, but instead of pelting us with cashews like usual, the little varmint starts clawing at our heads. At least those of us who got heads. Nurse Nice snares the little critter in a pillowcase and whisks him off to the infirmary, and then calls concourse. We circle our chairs around the nursing station.

“We are not human,” she says in a sexy, raspy voice. “We are F.O.O.D. Food objects overcoming displacement.”

Nurse Nice ain’t nothing but a crude charcoal drawing with a voice like Marilyn Monroe. But she’s one sassy cartoon sketch. Insists we call ourselves food “objects” instead of “mascots” or “characters.” Says we were created by our respective food companies to be objectified, to market food products and no more and that we’ve been sent here because our companies are done with us. This is her usual speech. Ain’t news to us. But we still can’t wrap our heads around it. Around displacement. Around no longer being able to fulfill our duties.

“We’re here because we no longer satisfy our companies’ needs,” she says. “We’re here to find a way to accept displacement and ready ourselves for the next phase of our journey.”

Ding O’Ling the former Noodle O’s court jester executes a painful “Ew! Eee! Ah! Ew! Eee!” dance in his chair to signify this kind of thinking don’t sit right with him. Zonkers the former ZAP! Cola puppet triggers a nebulae of blue sparks from the toy ZAP! gun sewn to his hand to suggest this logic don’t wash with him neither. I hurl a chain of yodels at her, indicating with varied pitches that we only got one purpose and that’s to represent what we were created for.

Nurse Nice looks at me. “Big Clump,” she says. “You should know better. You’re a cowboy. You ought to be the hero of this place.”

Then the dayroom fills with a crimson glow, and Ding O’Ling’s body stiffens.

“Oh God. Oh. My. God!” Za Za the former Pizza Barn pizza slice says through his pepperoni lips.

The bells of Ding O’Ling’s jester’s hat tinkle violently as the red beam of light ensnares him, lifts him up, whisks him off to Sam Hill knows where.

We all fall under the label of “animated” in some form or another. I’m a cartoon cowboy. Sir Gregory Twistleton III is a cartoon Englishman. Also Za Za, Numb Nuts, and the five Kablooey Kernel boogers—Rude Loog, Nasal Drip, Sizzle Chest, Lock Jaw and Pickle Puss. I reckon Nurse Nice is the least developed cartoon on account of her sketched-out appearance, but she’s been at the facility longer than all of us. Used to be the food mascot for Cardiac Carl’s, a Midwest grease pit where cooks gowned up like surgeons and “patients” got wheelchaired to and from the privy. But I reckon by the way she comports herself she’s as whole as any flesh and blood human.

The facility ponies up the elementals we need to get through each day. Vittles are how we connect with our food mascot pasts. Three times a day, Nurse Nice dispenses the necessaries from the storage room for us to carry out our former TV commercial routines. Zonkers opens a can of cola to an explosion of sticky brown fizz that catches him in his googly eyes, causing him to fly off his chair. Sir Gregory sits on his top hat and dunks Twisty Whips into his tea. I slop Clump Crunch cereal from a yellow Stetson hat the size of a wagon wheel. Sally Slice, a pimple-faced teenager on roller skates, rolls towards Za Za with the spinning disk of her pizza slicer raised as he screams through his pepperoni lips: “Oh God. Oh. My. God! Not again!” After the five Kablooey Kernel radioactive boogers each pop the carbonated rock candy into their mouths, their booger bodies fizz, shiver and jerk before a giant finger appears and flicks each of them against the wall where they detonate in a concussion of snot before rematerializing and exclaiming together: “What the Kablooey?!?”

Without Whirpletons to fling at us during vittles, Numb Nuts has taken to gnawing the fiberglass ping pong table till his gums bleed. Won’t be another delivery of Whirpletons by virtue of the white beam of light for at least a month.

Displacement from a food company can occur for a whole mess of reasons. I got put out to pasture when Clump Crunch Cereal abandoned the Western look and went with Cassius Clump, a rhyming boxer who bonks adversarial mascots on the head with gloves made of puffed corn. Zonkers got his pink slip after parents complained his zapper promoted gun violence. And Nurse Nice? A little bird told me that Cardiac Carl’s was buzzard food after one of their “patients” chowed down three Coronary Burger Baskets in one sitting and then suffered an actual coronary while trying to cash in his “eat three and get it free” rebate.

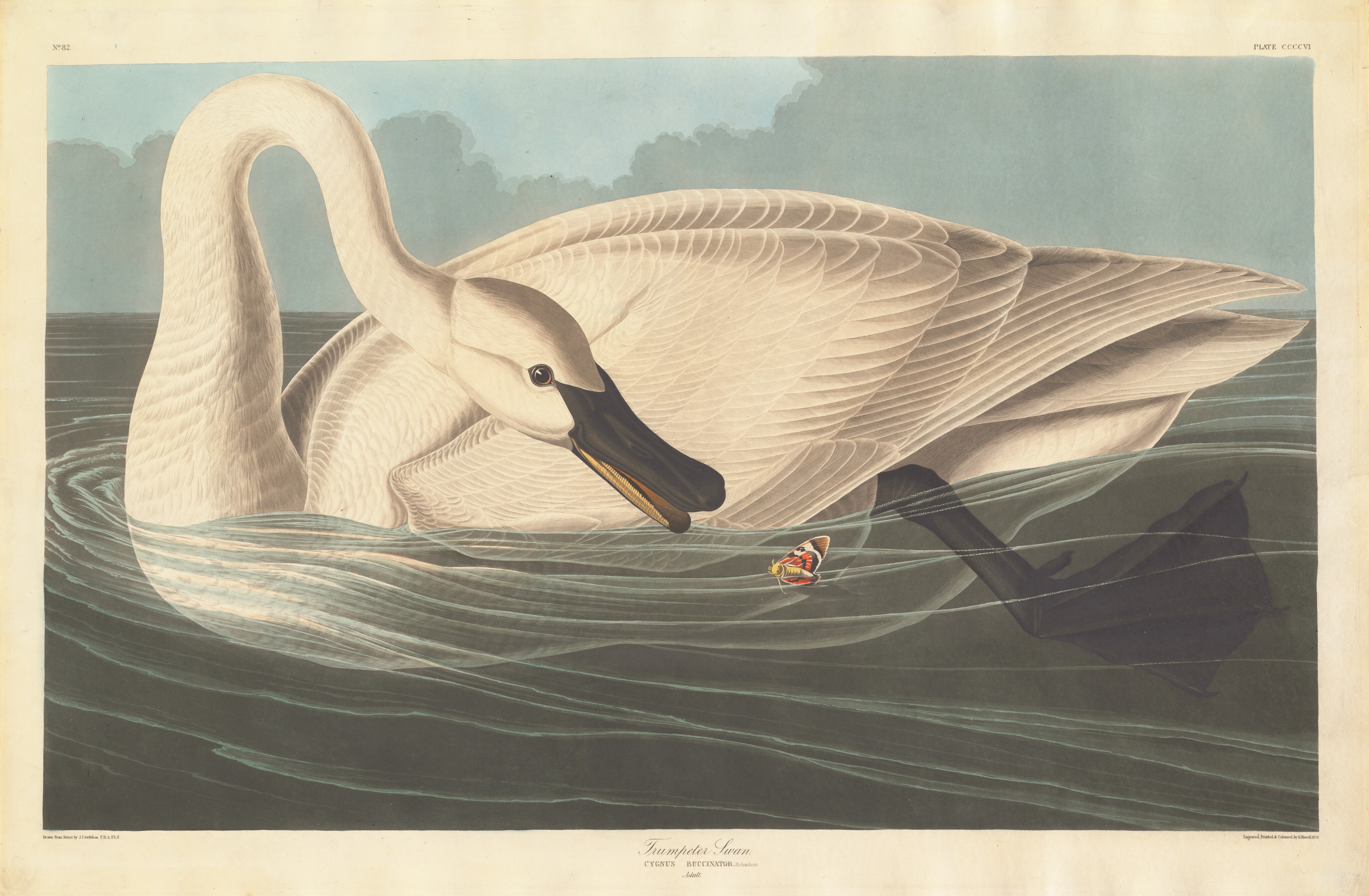

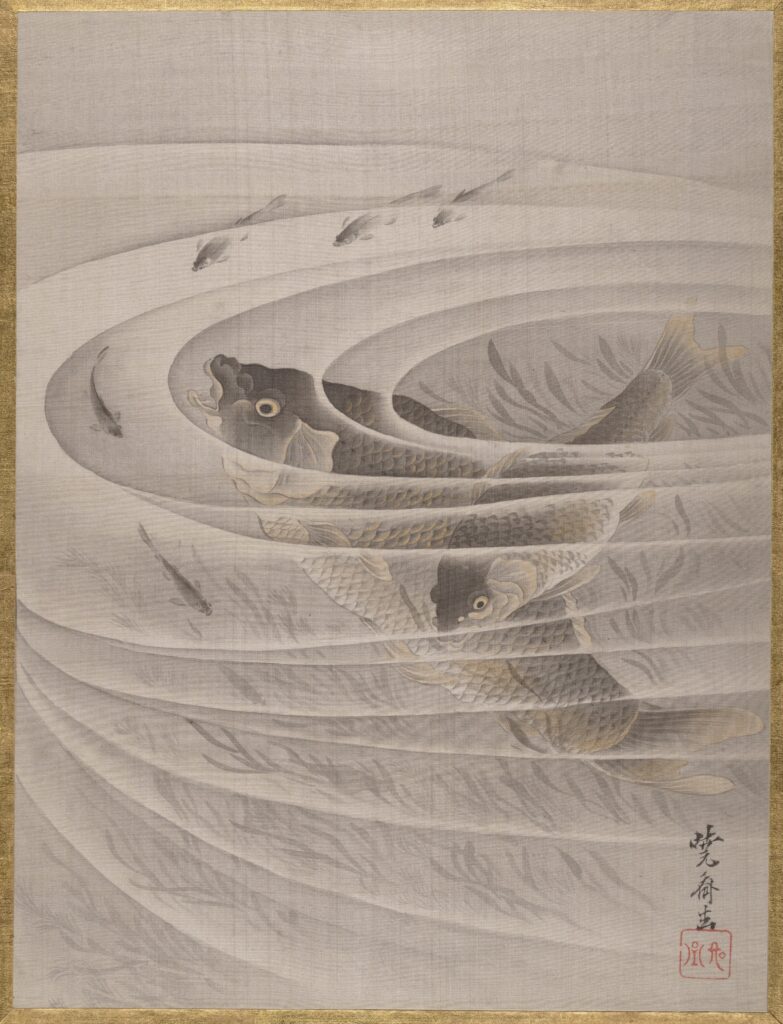

In between concourse and vittles, we occupy time with avocations. In front of the garbage chute, Sir Gregory acts out Hamlet; “To be or not to be.” Za Za works on his watercolors of colored water. Zonkers writes poetry while Numb Nuts, when he ain’t gnawing at the ping pong table, practices interpretive dance. Lately, the Kablooey Kernel boogers have been arranging the dayroom furniture “to honor Feng Shui.”

And me? My avocation is of the hush hush type. Dead of night shenanigans during bunk time, or de-animation, as Nurse Nice calls it.

“One can only be awake if one is alive,” she says. “And we are no such thing.”

Sir Gregory’s Twisty Whips have gone missing. Same M.O. as the Whirpletons. Nurse Nice says our thief is getting bold. At morning vittles, Sir Gregory splashes his face with scalding cups of tea. He throws a conniption and explodes a Kablooey Kernel booger against a wall. Nurse Nice pumps him full of Xanax and OJ and then wheelchairs him to the infirmary, wiggling them charcoal hips of hers.

Later at concourse, she tells us this is an opportunity from which we can all learn.

“Losing our connection to our past can expedite acceptance,” she says.

She gets us to chant in our individual vocalizations that only by accepting displacement can we transcend what we were and prepare for what is to come. Only then can we be at peace with ourselves before our eventual departure by virtue of the red beam of light.

A new food object turns up by virtue of the white beam of light. Pits, the bruised peach for Belly Acre Farms’ canned fruit. The white light giveth. The red light taketh away. I reckon that’s about as businesslike a system as it gets.

Pits corkscrews the upper half of his peach body, spots a brown dapple on his backside, and states his catchphrase: “Oh, dear. Did that leave a bruise?”

Numb Nuts lays a paw on his peach shoulder and whistles that life as Pits knows it is over. Nurse Nice proceeds to orient him, explaining the rules for the three vittles times, the need for avocations, the bunk arrangements; that this is merely a rest stop on the way to the next whatever. At evening concourse, Zonkers triggers an indigo nebula asking Nurse Nice if the red beam of light only comes for those who are at peace with their displacement.

“Acceptance of one’s station is irrelevant to the timing of their departure,” she says. “It comes whether you’re ready or not.”

She says Ding O’Ling didn’t have the cajones to accept his displacement. A ways back when we lost Phyllis the Freezer Barn Ice Cream Parlour Lips, Nurse Nice told us she never got nowhere on account she never shut her pie hole. But that’s all Phyllis was: nothing but a pair of lips with teeth. A big floating pie hole.

“Harrumph!” Sir Gregory says, acquainting Pits on Ding O’Ling’s fate—the red beam of light, what’ll happen to us all eventually.

“Oh, dear… oh dear…” Pits says.

Nurse Nice gets us to reckon a life that don’t include our former calling. No food product. No company.

“I want you to just ‘be.’”

But all I think about are the flocks of corn puff clumps I used to herd back at Clump Ranch, the yodels dancing off my tongue like firecrackers.

That was the simon-pure existence. Yessir. Everything in apple pie order.

De-animation don’t affect me like my compadres. Ain’t sure why. At bunk time, the others satisfy some notion of sleep. Sir Gregory cradles his top hat like a baby. Numb Nuts dangles upside down like a bat. Zonkers can’t lie down, something about his inner foam ear equilibrium, so he leans against the bunk post and fixes his googly eyes on the wall. I drop my hat over my face. But that’s all cock and bull. Back home at Clump Ranch, I’d roam the range for days without de-animating.

I mosey over to Nurse Nice. De-animated, her charcoal curves go as horizontal as a flapjack. Just lines on a mattress. The key to the storage room rests on a chain around her de-animated neck.

The light clicks on as you open the door. Atop the shelves lie boxes of Clump Crunch Cereal, Kablooey Kernels, ZAP! Cola, and the new crates of peaches for Pits. Sally Slice lies in a corner, de-animated. She’s a prop and not an actual food object, so she only animates during vittles. I realize for the first time Nurse Nice ain’t got no routine. There should be a shelf primed with Cardiac Carl’s chow: juicy cuts of buttermilk chicken deep fried and tied with bacon. I reckon this says something about why she runs the place. Maybe it’s got something to do with why she ain’t yet gone with the red beam of light.

The boxes of ZAP! Cola are closest to the hallway. I prop the door open with my yellow hat, wrassle each box one by one over to the trash chute.

With a soft yodel, I slot them in. Down they go.

When Zonkers gets wind of his missing ZAP! colas at morning vittles, he blames Nurse Nice. He sparks his zapper with a cluster of reds and purples, indicating she’s the thief and is doing this out of spite. The others grow as prickly as a bag of nails. Sir Gregory chest bumps Nurse Nice. Numb Nuts unleashes an accusatory whistle. Za Za screams though his pepperoni lips:

“Oh God. Oh. My. God! Not you!”

The Kablooey Kernel boogers lift the ping pong table over their heads and smash it against the wall. Pits rolls behind the nursing station and showers the room with thumb tacks and sharpened pencils. Nurse Nice tosses me a look: “See what you done?”

She knows I’m the culprit. I don’t know how, but she knows.

Numb Nuts takes flight, leaping onto those of us with heads and gouging at our eyes. Sir Gregory takes Zonkers by the puppet legs and spins him like a weapon. Sally Slice roller skates around the hallway, whipping infirmary scalpels into the walls.

Something whomps me on the head, and I de-animate.

I re-animate to a corolla of blue sparks. Zonkers is beside me in the infirmary, zapping he’s sorry I got hurt. Says one of the Kablooey Kernels accidentally hit me with a chair. His googly eyes rattle. He zaps that Nurse Nice is a lowdown dirty sneaking polecat and she won’t deny the deviltry she done. I yodel for him not to be too judgemental, that Nurse Nice is the best we got when it comes to figuring out what our time here means. Zonkers zaps that without his cola, he don’t know who he is no more. I yodel that I got hope something good will come of all this.

Later, Nurse Nice wiggles in. I yodel why didn’t she tell the others it was me.

“You need to be their hero, Big Clump,” she says, and she holds my hand for a moment. Then she wiggles out, and I cover my face with my hat.

She lies de-animated on her bunk. The key slides over her snaky hair. Zonkers jolts against his post and my cartoon heart bucks like a spooked colt. I freeze in place, watch him. Some kind of de-animated sleep jerk. I take a final gander at Nurse Nice, ironed flat on the sheets. She deserves better than she’s gotten. I don’t care what she says. She’s more than just some object. We all are, in one way or another.

Sally Slice proves most troublesome. But once her feet are over the lip of the garbage chute, she slides down lickety split. The peaches are the dickens. I drop a heap and spend a quarter hour chasing them down. The boxes of Kablooey Kernels eat up a fat slice of the night. I reckon that the Clump Crunch Cereal will be the hair in the butter, but it ain’t. With each box I fire down the chute, I grow lighter.

By daylight the storage shelves are bare. I got no intention of letting Nurse Nice take the fall this time. I stand beside the chute, holding my yellow hat over my heart, yodeling, waiting for the others to re-animate. I’ll tell them this is for the best, that Nurse Nice is right: we need to get out in front of the herd, to move beyond what we were and embrace what we are, what we are to become.

Nurse Nice is the first to enter the dayroom. Zonkers and Sir Gregory follow close behind. The others trail: the five Kablooey Kernel boogers, Za Za, Numb Nuts, Pits. They’re all looking at me, wondering what in Sam Hill I’m doing in front the garbage chute, yodeling. I’m about to yodel what I done when the room fills with a crimson light. Nurse Nice’s charcoal body locks, captured within. I yodel for her to stay, that we need her, but I know it’s hopeless. As she rises off the floor, I realize the light ain’t as crimson as I thought. It’s softer. The color of sweet tea or sour mash whiskey.

I take a final gander at her doodled face. The thin charcoal lines reveal a serenity, a calmness. She’s good. She looks like she’s ready to cash in her chips.

It’s a look we’re all aiming to acquire.

G. S. Arnold has an MA in English in the Field of Creative Writing from the University of Toronto and works at a career college in Toronto, Canada. His work has appeared in The Malahat Review, Echolocation, Event Magazine, Ninth Letter, Asia Literary Review, Glimmer Train, Prairie Fire, The Puritan, and The Master’s Review. His short story collection Pagodas of the Sun has been a finalist for the AWP Grace Paley Prize for Short Fiction and the Prairie Schooner Book Prize, and he has received numerous Toronto, Ontario and Canada Arts Council grants. Along with a Pushcart and a Journey Prize nomination, his stories have been short or long listed in contests such as the Writer’s Union of Canada Short Prose competition, the 2019 CBC short story award, and the Master’s Review Short Story Anthology Volume XI contest. He has recently finished his debut novel Sea of Clouds, set during the 1923 Tokyo earthquake.