I’ve become fascinated by birds. By no means am I a budding birdwatcher—I don’t have the patience nor does a pair of field binoculars with an eye relief of 15.1 millimeters fit into my shrinking budget. But I have discovered that the mourning dove’s melancholic coo calms me like pouring a glass of wine and listening to Sam Cooke croon throughout my kitchen.

For the past couple of summers, a family of mourning doves has thrived on our porch, their leather-brown nest of twigs and leaves glorious in its ramshackle construction. Their home is equally grotesque and beautiful, a one-bedroom flat overflowing with pea-sized droppings. If you stand on a ladder and peer into it, you’re likely to be both delighted and disgusted; as far as I can tell, the mourning dove is not a neat homemaker. But when you see the first blind slate-gray chicks raise their heads in mournful song, you forget about the specks of feces that inevitably rain down on your porch. You realize you’ve been invited to a celebration of nature, a welcoming of new life into the great web of things.

That said, what I love most about the mourning dove isn’t the chicks. It’s the way the mother and father’s brains are perfectly synchronized, how during a “shift change” one bird returns to the nest while the other bird flits away for nuts and berries. Often, this shift change happens simultaneously. On more than one occasion, a glass of Gamay swirling in my hand, I’ve watched the pair trade places without even so much as a passing glance at each other or the nest. Their instincts appear to be so finely tuned you could set them by an atomic clock. To me, it’s as mind-blowing as the language of bees. Or the fact that cheese exists.

This is the first summer our mourning doves haven’t returned to their home. Go figure: just when we started raising a baby in our own mottled nest, the doves have sought other real estate. Perhaps this is natural; bird pairs, like humans, might need to relocate for their own sanity. Or perhaps the doves no longer feel safe on our street in West Asheville. Recent evidence may support this theory.

Last summer, a stray cat we’ve subsequently labeled “The Murderer” crouched into our yard right as the first dove chicks haphazardly left their nest. I don’t know how long the chick waddled on the ground before the cat pounced. All I remember was the bird’s head hanging on, quite literally, by a single tendon, its body bloody and lifeless in the shadow of my tomato garden.

Unlike a smashed insect, snake, or even rabbit, a dead bird fills me with grief. Birds are supposed to soar effortlessly in the air, not suffer rigidly on the ground. They are symbols of love and hope, freedom and possibility. Even when I eat them, I prefer not to think of them clucking across a meadow or ambling out of a coop but riding the winds south for the winter. In my animal hierarchy, the bird occupies a tier near the top.

Even still, I understand that not all birds are created equal—both biologically and symbolically. Whereas one usually thinks nothing of consuming three hen eggs for breakfast, dining on an ostrich egg is (or at least “should be”) a memorable experience. During hunting season, a turkey is a prime candidate for an arrow through the gullet but not the peacock. The goose is stuffed, the chicken plucked, the mallard roasted. But one almost never sautés the cardinal. In short, be it for color, tastiness, intelligence, or abundance, some birds are more revered than others. And when it comes to reverence, few birds are more celebrated than the swan, that feathery symbol of purity and love. You can kill the sparrow, but you must always spare the swan.

Two months ago, three teenagers in upstate New York killed and ate a swan. The three teens allegedly hopped over a fence and decapitated Faye, the swan mother, with a knife. Then, they stole the cygnets. When they were caught, the teens confessed to eating Faye, claiming they thought the swan was a duck. Fortunately, police recovered all the cygnets; they arrested and charged the teens.

As one can imagine, the small town in upstate New York felt a mixture of grief and elation: immense sadness over the death of beloved Faye and spirited satisfaction over the apprehension of the avian murderers. Yet I couldn’t help but find the town’s response somewhat odd. Had the victim been a farmer’s pig, the teens still would have been charged, but the injustice would not have seemed like such an intolerable act. Pigs, after all, are routinely slaughtered. Moreover, had the fowl been a plain old duck, the town may have been outraged, but I can’t imagine the story reaching a national audience.

There’s something about killing a swan that borders on sacrilege. It feels like a demonic act, one that’s sadistic no matter how goose-like the animal tastes. Eating a swan simply doesn’t feel right, and I had to know why.

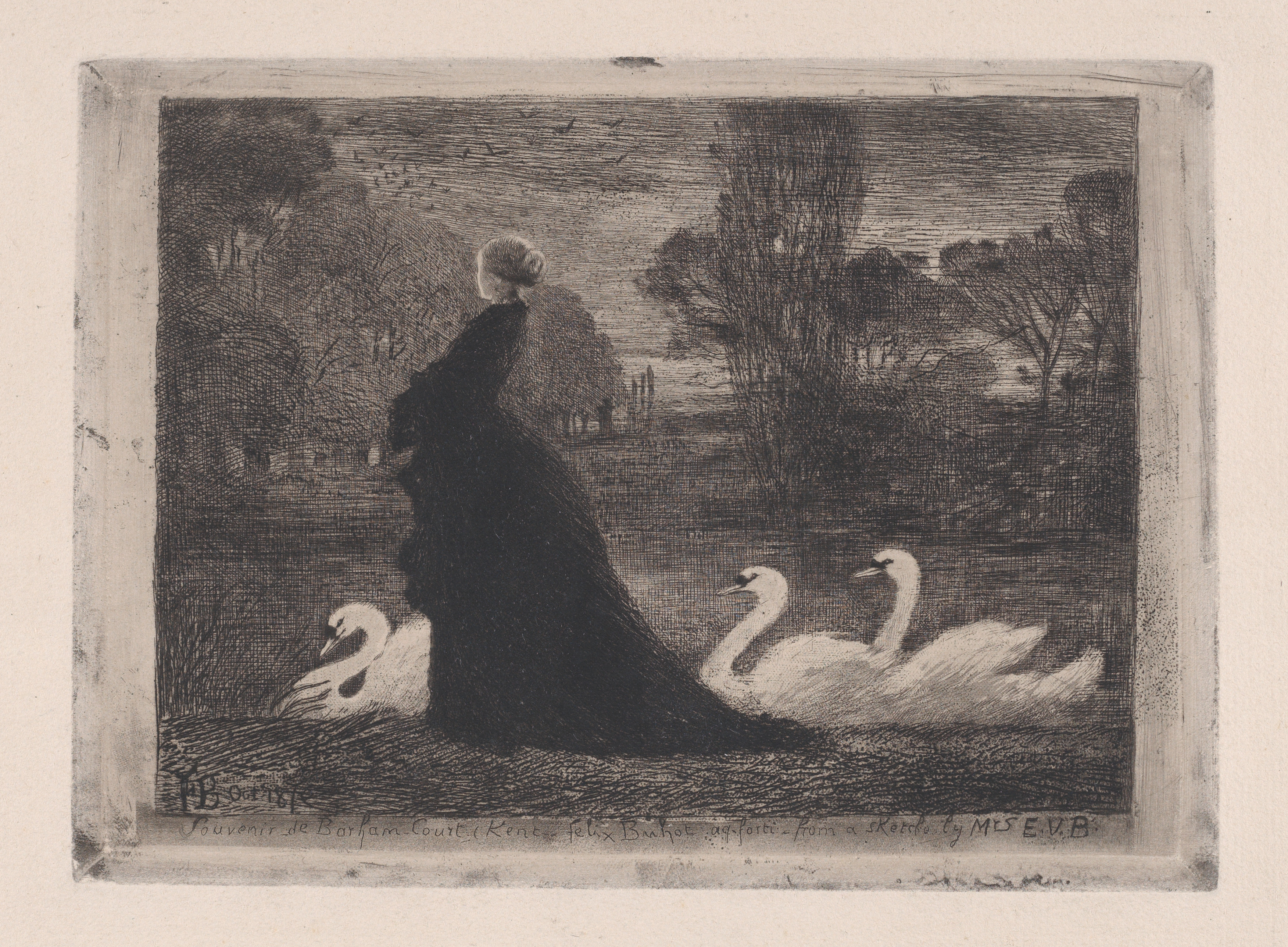

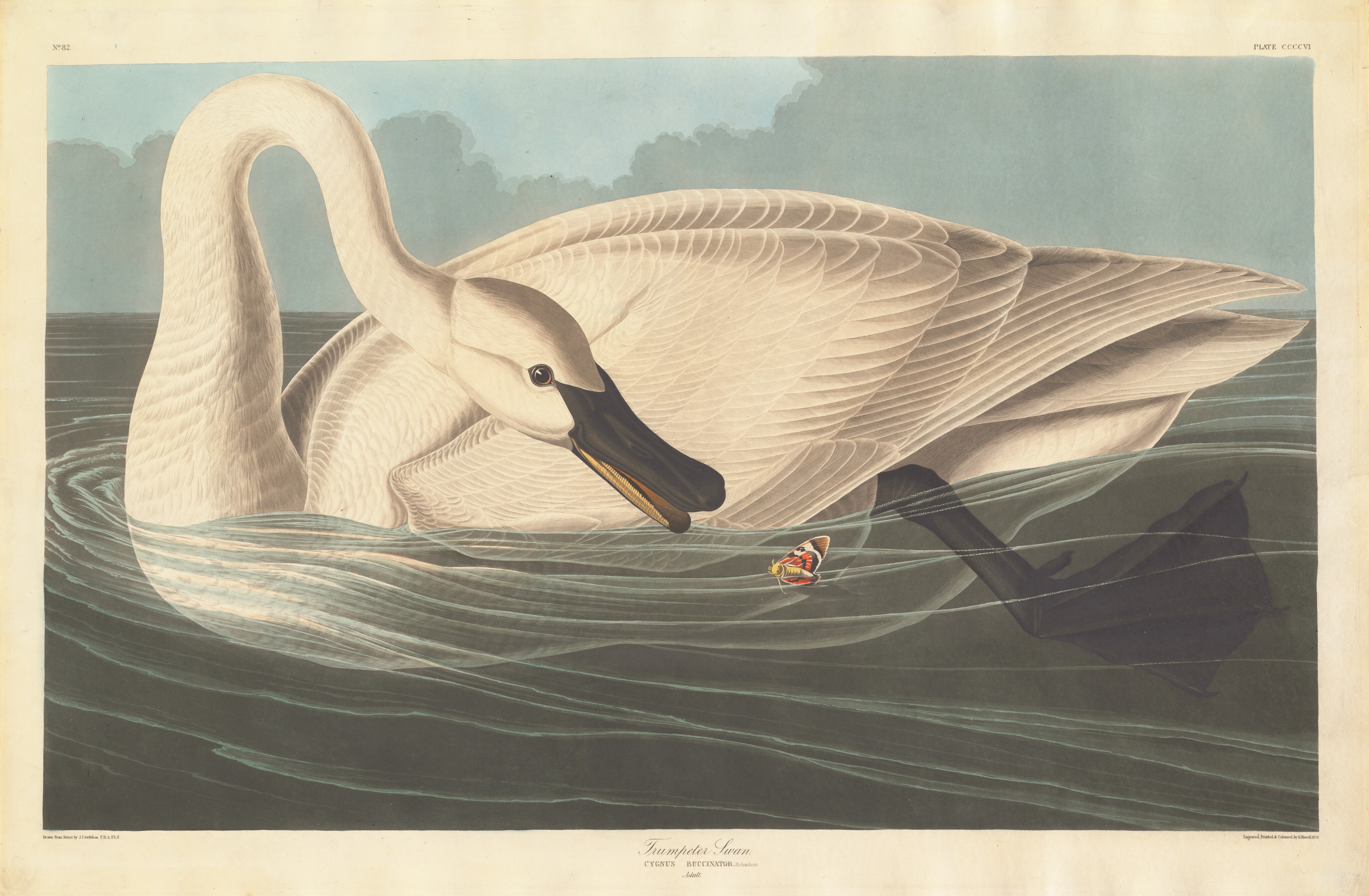

Regardless of whether the swan is a trumpeter or mute, black or tundra, the animal is beautiful. Exceedingly so. In many ways, the swan feels like the platonic ideal of a bird, its long, curved neck swiveling through the lake’s cool breeze like a periscope. With its wings back, the swan looks deceptively rideable—as if it could carry Neptune himself. The swan is also famous for its coupling. Unless a pair “divorces,” swans mate for life. No wonder we’ve appropriated the bird’s sleek, plump body for romantic canal rides.

Like most majestic animals, the swan occupies a special place in mythology. In Greco-Roman myth, the swan is a symbol of love, purity, immortality, and the soul. And yet, perhaps the most well-known (and surely infamous) myth concerning a swan involves the rape of Leda. The story goes that Zeus took a swan’s form to rape Leda on the night she slept with her husband, King Tyndareus. For Yeats, this grotesque, forced coupling results in the birth of the Greco-Roman tradition and thus the modern Western world:

A shudder in the loins engenders there

The broken wall, the burning roof and towe

And Agamemnon dead.

Being so caught up,

So mastered by the brute blood of the air,

Did she put on his knowledge with his power

Before the indifferent beak could let her drop?

Though Yeats’ history is interesting, I’m infinitely more fascinated by the juxtaposition of the swan imagery with the violence of the sexual act. If society traditionally views the swan as a symbol of love and hope, mythology suggests that the animal simultaneously embodies violence, rape, and death. When I picture a swan boat floating down a canal, I think of lovers intertwined. I also think of “A sudden blow: the great wings beating still.”

The swan isn’t confined to the Greco-Roman tradition. In Norse mythology, the Valkyries donned swan outfits to ferry the valiant dead to Valhalla. Similarly, in Hindu theology, the god Brahma rides a swan. In fact, Hindus who’ve attained enlightenment are often called Paramahamsa or “Supreme Swans.”

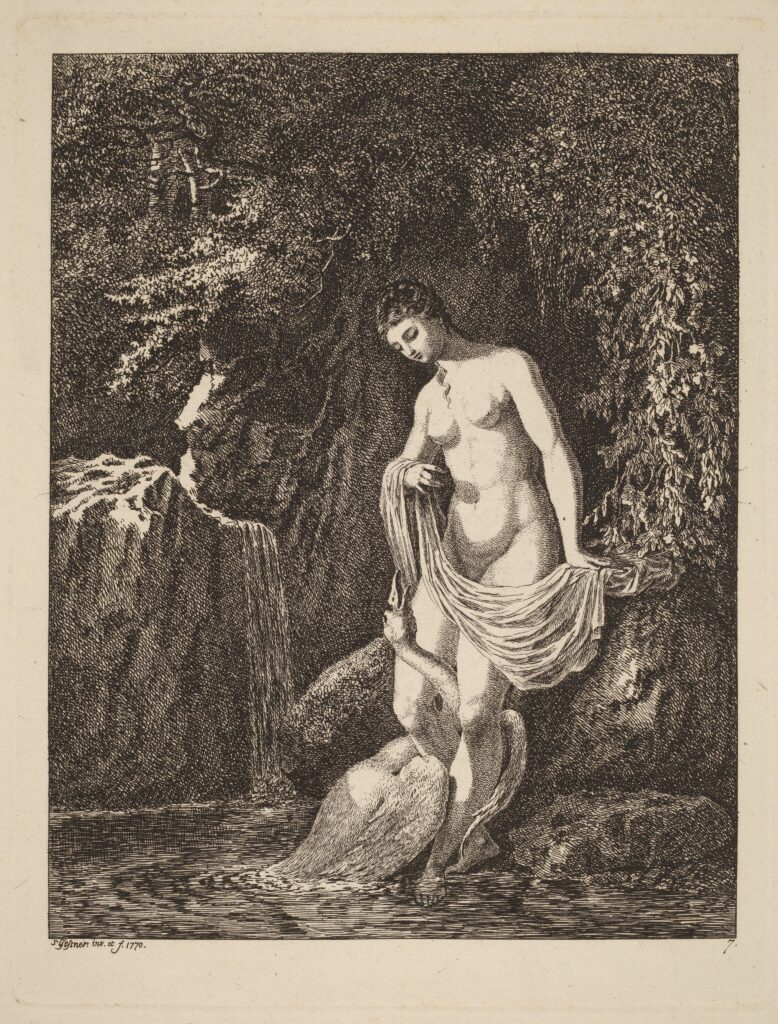

Given the swan’s beauty and grace, the animal often functions as the object of desire, an attribute encapsulated in myriads of “swan-maiden” myths found throughout the world. Though the specifics of these folktales differ in slight degree, they share a common thread: swans cast off their feathery skins, revealing the bodies of beautiful women. Unbeknownst to the swans, a hunter watches from a distance. As the swans enjoy a naked swim, the hunter steals one swan’s clothing, forcing the swan-turned-woman to become his wife.

While the swan-maiden folktale is less violent than its Leda counterpart, the swan still takes on a sexual dimension, still forms the center of a story revolving around possession and control. For all its regality, grace, and splendor, the swan is complicated by human lust. It is this struggle between the need to preserve beauty vs. the drive to possess it that makes the swan-as-food seemingly unpalatable.

Until the late 17th century, the English considered swan meat a delicacy. In fact, many swan recipes remain from this time. In her 1670 cookbook titled The Queen-like Closet; Or, Rich Cabinet: Stored with all manner of Rare Receipts For Preserving, Candying and Cookery, Hannah Wolley provides a recipe for baked swan:

Scald it and take out the bones, and parboil it, then season it very well with Pepper, Salt and Ginger, then lard it, and put it in a deep Coffin of Rye Paste with store of Butter, close it and bake it very well, and when it is baked, fill up the Vent-hole with melted Butter, and so keep it; serve it in as you do the Beef-Pie. (Wolley)

Delicious as the recipe appears, not every diner could enjoy filling up the swan’s “vent-hole with melted butter.” By the 16th century, a court case between an English monarch and two commoners found that swans were, in essence, government property. This meant that only the English elite could feast on swan meat. The poor were restricted from enjoying the bird doused in butter sauce and nestled on a plate of potatoes.

However, even the English elite soon considered eating swan meat taboo. While we may never know the exact reasons for the changing tastes, Renaissance art, especially Leda and the Swan, helped codify the bird as an object of grace, beauty, desire, and sophistication. Like the dog and horse in Western cuisine, metaphor and symbolism saved the swan.

Contrary to popular belief, no extant species of swan are endangered. Nevertheless, the swan is a protected bird in the U.S.—a holdover from the overhunting of swans in the early 20th century. Other countries also have laws on their books protecting swans from consumption.

If the rarity of the fowl isn’t the reason for the swan’s legal status, what is? Again, the bird’s emotionally charged symbolism is mostly to blame for the refusal of contemporary eaters to partake in swan feasting. In some circles, diners value the bird on such sociocultural and mythic levels that even the mere thought of preparing a swan is met with protest.

In 2013, for example, a German chef faced severe criticism after adding swan to the menu. Although the chef’s restaurant, a local farm-to-table operation on the Baltic Sea (where it’s legal to hunt mute swans), argued for the necessity of serving the “region’s offerings,” local protests forced him to eighty-six the bird. German diners seemingly could not stomach the thought of eating the regal, glorious swan.

I’ve long been fascinated by our refusal to eat some animals while gleefully sticking a fork into others. All things being equal, why does society largely turn a blind eye to chickens slaughtered in Tyson’s bloody factories but views swans with impeccably clear vision? To be sure, I’m not advocating for the consumption of swan. But I do wonder about the consequences of attributing human virtues to animals—especially in a symbolic sense. Our belief that the swan is sophisticated spares the animal. The same cannot be said for the pig. Although the pig is highly intelligent, the creature’s supposed “lack of sophistication” (if animals can even possess such a thing) makes it easier to justify its transformation into ham, pork loin, and bacon.

For Michael Pollan, these gastronomic preferences stem from the “omnivore’s dilemma,” that conscious (sometimes unconscious) choice about what to dine on in a world of plenty. According to Pollan, “When you can eat just about anything nature has to offer, deciding what you should eat will inevitably stir anxiety…” (3). In the case of the swan, art and mythology reduce much of this anxiety: we are taught to believe in the swan’s superiority to other fowl. To put it another way, in anthropomorphism we trust.

Could more anthropomorphism ultimately result in a vegetarian West? Would believing in the majesty of the cow lead to a rejection of beef? I’m not so sure. Moreover, I don’t know if the conscious anthropomorphizing of animals is inherently a good thing. It may help us become more compassionate of the animal world, but it will also surely exacerbate the very human drive to apply a harsh moral code to the kingdom of fauna. Society cannot abide the killing of the “good” swan, but it gives the “evil” snake no quarter. I’m much more inclined to believe that evilness resides in the swan as much as goodness lives in the snake.

I’m at least relieved that people are outraged by the beheading of the swan in upstate New York. To kill a beautiful creature with such wanton abandon seems an apt metaphor for our times. Even the most graceful among us are destroyed by bloodlust and stupidity. Even our most cherished symbols are subject to erasure. When I think of Faye separated from her cygnets, I think of immigrant families torn apart at the border, of police brutality killing the fathers and mothers of BIPOC households at routine traffic stops. If we truly believe that all humans are beautiful by virtue of their ability to infuse the world with food and music, poetry and purpose, what else could these attacks be if not assaults on the very idea of beauty? Like the massacre of swans, state-sanctioned violence against marginalized communities functions to remove beauty from the world.

Moreover, I think of cruelty for the sake of politics, politics for the sake of cruelty. I think of a deep-rooted hatred that exists simply because it can. The act of killing and eating Faye seems both rational and irrational: unthinkable in a world of “civility” but almost inevitable in a culture subsisting on a diet of violence and intolerance.

After reading about Faye’s murder, Yeats’ “Leda and the Swan” wasn’t the first artwork that popped into my mind. It was Dali’s surreal depiction of swans in his 1937 painting Swans Reflecting Elephants. In the painting, three swans float on a lake which cuts through a fiery, desolate landscape, a landscape that appears to have been recently bombed. Above the swans, the bruise-blue sky holds the cream of melting clouds. The trees are leafless and warped. But the three swans look gorgeous and regal, their arched necks and plump bodies reflecting the shapes of elephants in the water.

The painting asks us to contemplate the illusion and irrationality of “seeing” the world as it appears. But it also asks us to consider the complex entanglement of all living things. It asks us to ponder the purpose of beauty in a world increasingly bent on destroying itself. I stare at the painting intently, thinking of the juxtaposition between the empty dove nest on our porch and our own home, bristling with the energy of a newborn. I think of my exhausted wife, my sleeping daughter. I imagine Dali’s swans swimming past their ravaged landscape with cygnets in tow, the wedge finally reaching open water.

Works Cited

- Pollan, Michael. The Omnivore’s Dilemma: A Natural History of Four Meals. New York: Penguin Books, 2006.

- Wolley, Hannah. The Queen-like Closet; or, Rich Cabinet: Stored with all manner of Rare Receipts For Preserving, Candying and Cookery. Very pleasant and beneficial to all ingenious persons of the female sex. R. Lowndes at the White Lion in Duck-Lane, near West-Smithfield, 1670.

Joshua Martin is an Assistant Professor of English at Tusculum University and the poetry editor of The Tusculum Review. The winner of the 2023 Randall Jarrell Poetry Award from the North Carolina Writers’ Network, his poems, essays, and reviews have been published or are forthcoming in storySouth, Rattle, The Kenyon Review Online, Baltimore Review, Carolina Quarterly, The Bitter Southerner, and elsewhere. His first book, Earth of Inedible Things, won the 2021 Jacar Press Book Award. He lives with his wife and daughter in Asheville, North Carolina.

Comments are closed.