On Karen Pinchin’s

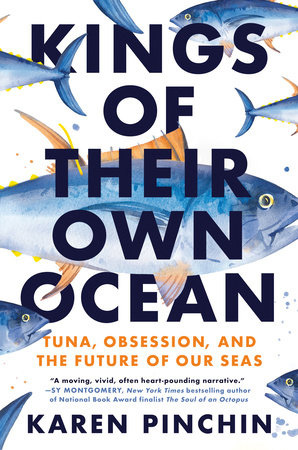

Kings of Their Own Ocean

(Dutton, 2023)

The art of effective misinformation always contains a grain of truth.

Recently, I was listening to climate skeptic Anthony Watts spew off flaws in climate science methodology, attributing rising temperatures to changes in measurements. He explained that “weather stations have been slowly encroached upon by urbanization and siting issues over the last century, meaning that our urbanization affected the temperature… Anyone who’s ever stood next to a building in the summertime at night, a brick building that’s been out in the summer sun, you stand next to it at night, you can feel the heat radiating off of it.”1 While this is a true phenomenon called the Urban Heat Island Effect, he didn’t explain that climate scientists carefully correct for this in their measurements, and that places untouched by pavement, such as the middle of the ocean, are still experiencing increased temperatures; how is a listener supposed to contextualize his authoritative statements?

In an age when information is shared at the speed of light, where fake news can be deliberately crafted to mimic the style and format of legitimate news sources, distinguishing between credible and misleading information is increasingly challenging. As a researcher myself, I feel compelled to defend the scientific method and uphold the value of expertise and credentials as pillars of reliable knowledge. But by nature of defining communities and defining the haves and have nots of expertise, there is the flip side that definition necessitates exclusion.

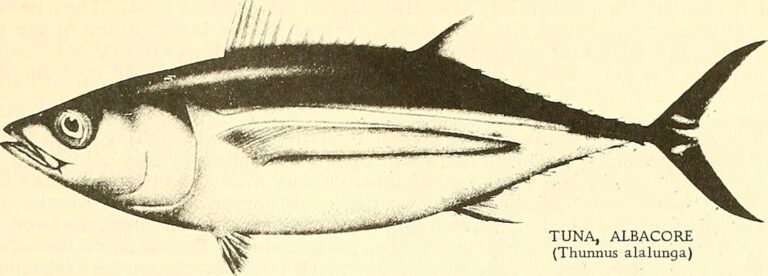

The complex role of scientists is a touchstone in the book Kings of Their Own Ocean: Tuna, Obsession, and the Future of Our Seas. The king in question is the bluefin tuna, a sleek torpedo-like creature that can shoot through the water at speeds up to 40 miles-per-hour. They are also one of the ocean’s apex predators, influencing and controlling their entire food chain. In this book, journalist Karen Pinchin tells a specific but familiar story, taking a long view spanning several centuries, from the tuna’s initial abundance to the alarming decline and subsequent efforts to implement sustainable fishing practices in the face of growing sushi demand. Early in the book though, Pinchin already hints at the unique lens through which this story will be told: a story where the role of science is continuously challenged, revered, and redefined throughout the book, highlighting science’s ability to educate, whilst maintaining a critical eye to vulnerability to exploitation.

A prime example comes early in the book. Pinchin describes the monumental 1981 meeting in Spain, where scientists and policymakers gathered to respond to the heavy fishing pressures the sushi industry has put on the bluefin stock. Facing a stalemate between North Americans who wanted catch limits to preserve the tuna population and Europeans who refused quotas, the delegates agreed to draw a line at 45° west longitude. This line supposedly reflected scientific belief that bluefin tuna tended to stick to the coasts without significant migration, but nature rarely births straight lines. As early as the 1970s, there was growing evidence that the powerful bluefin tuna, a warm-blooded powerhouse with exceptional speed and vision, simply did not respect this imaginary boundary line and was highly migratory. Regardless, this line gave North American policymakers the claim that they could ostensibly control their half of the fish stock.

I am an environmental researcher, albeit very different from the types described in the book (I’m mostly click-clacking on my computer rather than chasing magnificent sea creatures). But ultimately all researchers are like cold case detectives, interpreting clues to piece together a truth that no one will ever tell you is right or wrong. Acknowledging uncertainty is integral to the scientific process, but it doesn’t always make for a straightforward headline. Pinchin is keenly aware of this, of the scientific uncertainty that can slide easily into manipulation. As a researcher, I live with scientific uncertainty every day, but also fear the growing distrust of scientific expertise. How do we know if the policymakers in Spain were bad actors? They certainly feel far from the climate deniers running rampant today. How can I distinguish between scientific uncertainty versus scientific manipulation?

Pinchin’s answer to this comes in the form of Rhode Island boat captain Al Anderson, lifelong fisherman and bluefin enthusiast. Enduring a difficult childhood and born with a clear hunger to learn, fishing offered solace and fascination. His love and curiosity for the bluefin tuna in particular led him to abandon the notion that to be a fisherman meant you had to kill. Al “extolled the satisfaction and karmic virtues of bluefin tagging” and eventually made a living taking clients out to catch, tag, and release fish. In his lifetime, Al managed to tag and release more than 60,000 fish, contributing immensely to early data on the bluefin population, and redefining the capacity of citizen scientists. At times, I felt his resolve approached the point of disorientation, illustrating a level of dedication akin to religious fervor. Al’s method embodies an Edenic vision of the scientific process: a yearning to understand the natural order and a collection of data in service of that curiosity—pure and untainted, an ideal of what we hope for in scientific endeavor. But inevitably, science must engage with bureaucracy, must swim through the social structures that often mire it in murky, politicized waters.

Zeroing in further, Pinchin’s book is woven around one particular bluefin tagged by Al, dubbed Amelia, who was caught three times. The first time in 2004 Narragansett, Rhode Island, by Al. The second time, Amelia was caught in Cape Cod by Molly Lutcavage, a scientist using advanced satellite tagging techniques to break open the data uncertainty that plagues fish science. Pinchin gives us a deeper look at Lutcavage’s career: in particular, her rivalry with Carl Safina, a conservationist. Whereas Lutcavage directly engages fishermen in her research, Safina aims to fight against the industry. Their rivalry encapsulates the difficult contradictions in science; even two people with good intentions can come to vastly different conclusions.

A decade later, Amelia is caught a third and final time, all the way in the Mediterranean—a testament to the strength of the bluefin whilst directly challenging the 45° line. But as much as this is a story about the fallibility of science, it is also a case study of a messy, nonlinear scientific process that is working. The true test of the scientific method is not how often it gets things right, which is inherently unknowable. The true test is the ability for our social structures to take in new evidence and reincarnate existing knowledge. Amelia’s journeys and Al’s obsession were part of a reincarnation of bluefin expertise, pushing shifts in fisheries’ management policy.

Pinchin nicely summarizes this idea in her last chapter, writing that, “Science doesn’t hold abstract authority. It is a practice and a profession incrementally built by trial and error over generations, and I am always wary when any one person or institution claims power or authority over its gradual, deeply human process.” Her final thoughts offer comfort for our present predicaments, reminding us that just because there are climate deniers does not mean science is not working; rather, it underscores that science is functioning in a society fraught with power struggles. We should listen to scientists because they do have specific expertise, but in the wrong hands, expertise can look a lot like a power grab. Amelia and Al are a reminder that scrutinizing expertise and expanding the pool of knowledge creators leads to a richer catch of insights.

- “Why the Global Warming Crowd Oversells Its Message,” Spencer Michels with Anthony Watts, PBS News Hour, September, 2012. ↩︎

Yixin Sun is an environmental researcher, currently pursuing a PhD on environmental and development economics at the University of Chicago. She loves a good story and a good dataset, and especially loves it when you combine the two.