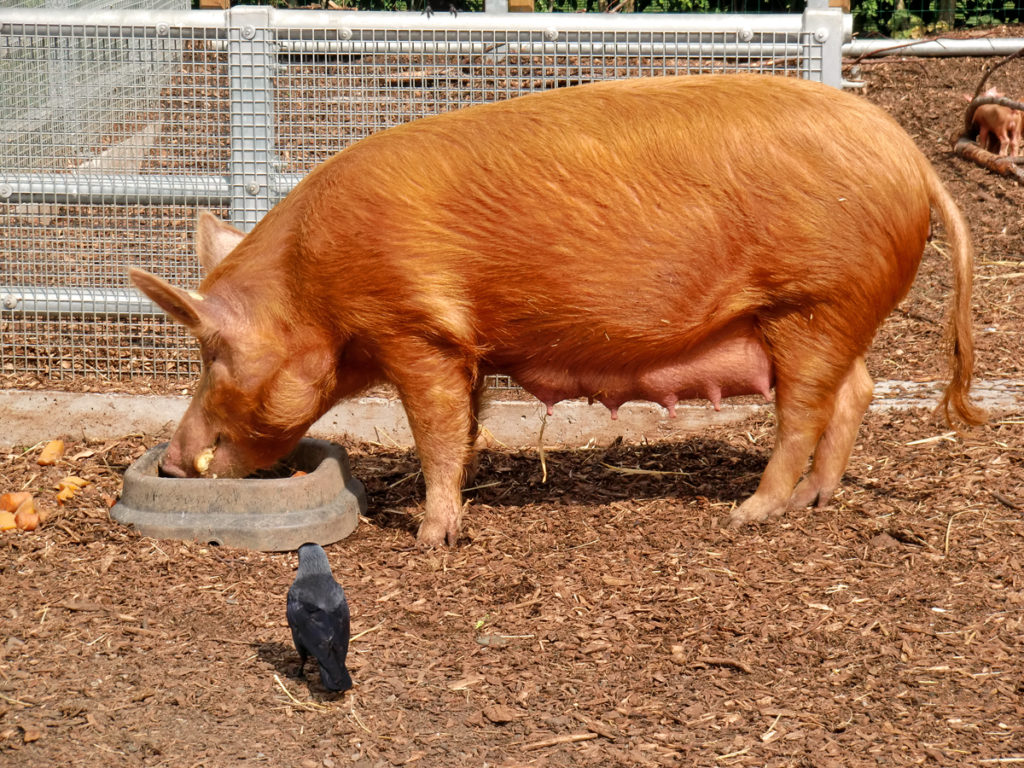

The border fence, the Rio Grande (or Río Bravo) and “La Mojada” (by Mark Clark). Seen from Brownsville, Texas. Photograph by Virginia Ramos (Hope Park, 2010-).

The border fence, the Rio Grande (or Río Bravo) and “La Mojada” (by Mark Clark). Seen from Brownsville, Texas. Photograph by Virginia Ramos (Hope Park, 2010-).

He was drunk by late morning, as usual.

Toni watched from the kitchen. She constantly worried about where she would go, where she would live after having spent her whole life caring for that family, cooking for them, cleaning for them, and being the Mexican nanny of the boy kings, man-kings in the Southmost part of Texas. Toni had only been 16 when she decided to cross that big river as a mojada, escaping from her ghosts and from the hopelessness of her homeland. She had given that family the best years of her life.

Now that Los Señores had died, it was only her, her kitchen and that drunken man-king she helped to raise. He was once her consentido, her favorite one, and now he was her only hope. She should have left just after Don Eduardo had died. But Toni had nowhere to go. She couldn’t go back to Mexico and live in the countryside, en el ejido, on the other side. She couldn’t go back to the poverty, the place where her relatives hurt her.

“You’ve ruined my life,” Norma screamed at him. “Look at yourself, you look like a fool. Bobo, pendejo, pinche borracho! I’d rather go back and teach at the community college or at the new “Rio Grande University” and take care of my former students; they need me more than you do: so much potential, so much promise in a place that finally hires bilingual BA’s.”

“I need you mamita,” he said in his usual Spanglish. “No me dejes solo. Te amo, te necesito [Do not leave me alone. I love you, I need you]. Please Mamita, please”. He almost cried, but instead swallowed his drink very fast. “We are made for each other. You know we have good times together. And I’ve been able to hold the liquor better. People hardly notice the drinking. Casi ni se nota!”

Norma shook her head in disbelief. “Don’t notice? Of course they notice. Can’t you tell their disrespect? Their disgust? I think their thoughts for you are beginning to rub off on me. My friends ask me what I’m still doing with you.”

“You could move in with me, Mamita, permanent. Tu y yo juntos, tu y yo aquí. My brothers have their own homes; they don’t need the house; this house is your house, yours and Toni’s house.”

Although blurry, his eyes showed some panic in that once handsome face deteriorated by a life of craziness, unhappiness, and excess. This argument seemed worse than all the others. Mamita was determined to leave this time. He was on his last legs with this woman too: no job, but outstanding tickets for what should have been DUI’s written by those friendly cops for whom his surname went a long way.

Toni loved living in that big house, her home for almost five decades, una hacienda in this little border town near the big river. In the back of the house, a resaca flowed from the river that was connected to the Gulf of Mexico. It was like living in a park, with palm trees all around the place, flocks of noisy and shiny green parrots, and flowers of different colors bursting from bushes all year around. She had been lucky all these years. Al otro lado, things would have been very different, and not in a good way.

Toni had nine sisters and brothers, a stupid mother and a drunken father. She used to take care of her siblings while her older sisters worked as maids with rich families in Matamoros or on the other side—and they sent money, but they never came back. And Toni did the same. But before she left, Toni used to cook for her brothers and sisters, for her drunken father and for her stupid mother. There she became the best cook among the best. There she learned to make tortillas a mano [from scratch], and also enchiladas, burritos, frijoles charros, tamales fronterizos, and also salsas of different types.

Toni remembered the dusty, dry brown scorched earth where she and her siblings were raised. Her parents could barely scratch a living for their big family from that piece of land, unproductive and dry. Her father worked at a ranch part of the year. Her mother spent the whole day raising kids, hauling water to the house, keeping everyone clean. Water there was always hard to find and heavy to carry.

Norma, in exasperation, shot back at him. “This house? I don’t need to live here. I have money too. My apartment suits me well. It’s a place to escape from you, borracho infeliz. And I’ve stayed with you, supporting you, and seeing you falling at this house. I don’t need you or your house. I’m out of here.”

Toni had nowhere to go. She had no papers, no education certificates, no youth, no pride, and no land. She was old; her energy was spent. She rarely went out except to shop at that small and smelly HEB located in old downtown, where only Mexicans shopped. She had given this family everything. She was entitled to something—at least a nice place to live her remaining years. If Norma didn’t stay here, keep that drunken fool alive, and justify this big house as a home, Toni’s living arrangements would be in jeopardy.

Toni thought about her childhood, or the little childhood she had before she grew up to work and bring the little money from her job as a maid. She went to school, but didn’t even finish la escuela primaria. Toni vaguely remembered learning about history, but there was a topic she remembered relatively well: the U.S. invasion of Mexico—or when her country lost half of its territory that ended up being gringoland, or part of the United States. Many fronterizos like Toni had learned, since elementary school, that lesson really well. That topic fed her resentment; a resentment against that family, against drunken men, against successful women like Norma, and against the United States. Toni still remembered at times her history textbook that talked about El Coloso del Norte—the country that had to steal and cheat to take more than a half of Mexico’s land. For Mexicans this was an “invasion;” and for los gringos it was a war: the Mexican-American war. With talk of war, los gringos thought they could justify the looting, or a very, very unfair deal to get Mexico’s land.

Toni chuckled to herself with resentment, but the words came out. “This very house and land, once part of Mexico.” She felt entitled to it for that reason too.

“What’s that noise,” he and Norma both asked together. “Is Toni around?” he asked. “We’d better lower our voices. She lives here too. Let’s have Toni make a good meal for us. We’ll feel better after some food is in our stomachs. Then we can talk about it again later. You know I need you. Mamita, please.”

Sighing, Norma said, “Well, okay. I’ll shower and then let’s eat.”

Toni would cook for Norma to make her stay. Toni began planning the meal, its ingredients and special herbs. Toni wanted to make something that Norma would love. Norma was vegetarian, but loved Toni’s spices, her salsas. Toni would prepare calabacitas rellenas, and enchiladas verdes; no meat, only cheese, salsa roja for calabacitas, salsa verde for enchiladas. This lunch would be especial–pico de gallo, guacamole, frijoles charros and hand-made blue corn tortillas.

Toni’s kitchen was full of jars, with all types of herbs and roots: oregano, ruda, chamomile, eucalypt, cola de caballo, ginger, tomillo, lavender, tila, mate, dandelion, ginkgo biloba, you name it. If someone has a headache or a stomach pain, Toni what to give. And Toni also knew the best herbs and roots for love spells, Eve roots, Adam roots, hibiscus, jalap root, patchouli, rose, rosemary, and toloache.

She kept the toloache hidden. Toni knew toloache could be dangerous: if a person sweats too much, if her heart beats too fast, if she wants to vomit, if she’s dizzy, she’s taken too much. Toni heard of someone even hallucinating or dying from toloache.

A special meal for Norma, she thought, while she took out the ingredients. Y un ingrediente más, un ingrediente especial. She opened the magic drawer, singing to herself about the herb to add. “Toloache para Normita, toloache para la Mamacita.” Toloache, the love poison, would make Norma forget, make her love the man, maybe just for a while, but for a while she will not leave. One dose as needed. But this was not the first time.

“Porque el amor cuando no muere mata, porque amores que matan nunca mueren.” When love does not die it kills, and loves that kills never die, Toni sang. “Toloache can make you love, but Toloache can also kill,” Toni remembered her grandmother’s words.

When the meal was ready, Toni served it, watching as Norma bit into the one of the calabacitas rellenas. Norma smiled.

“We’ll always be together. Don’t worry,” she said to the man.

Guadalupe Correa-Cabrera

Guadalupe Correa-Cabrera

Guadalupe Correa-Cabrera (Ph.D. in Political Science, The New School for Social Research) is Associate Professor at the Schar School of Policy and Government, George Mason University. Her areas of expertise are Mexico-US relations, organized crime, immigration, border security, and human trafficking. Her newest book is titled Los Zetas Inc.: Criminal Corporations, Energy, and Civil War in Mexico (University of Texas Press, 2017; Spanish version: Planeta, 2018). She was recently the Principal Investigator of a research grant to study organized crime and trafficking in persons in Central America and along Mexico’s eastern migration routes, supported by the Department of State’s Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons. She is now working on a new book project that analyzes the main political, cultural, and ideological aspects of Mexican irregular immigration in the United States and US immigration policy entitled “Illegal Aliens”: The Human Problem of Mexican Undocumented Migration. At the same time, she is co-editing a volume titled North American Borders in Comparative Perspective: Re-Bordering Canada, The United States of America and Mexico in the 21st Century (in contract with University of Arizona Press, forthcoming Spring 2020). Dr. Correa-Cabrera is Past President of the Association for Borderlands Studies (ABS). She is also Global Fellow at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars and Non-resident Scholar at the Baker Institute’s Mexico Center (Rice University).

Kathleen Staudt

Kathleen Staudt

Kathleen (Kathy) Staudt, Professor Emerita, recently retired from the University of Texas at El Paso where she taught courses on borders, women, and politics for forty years and became an adopted fronteriza. Active in social justice community and women’s organizations, her latest of twenty books is Border Politics in a Global Era: Comparative Perspectives.

Guadalupe Correa-Cabrera

Guadalupe Correa-Cabrera Kathleen Staudt

Kathleen Staudt