The morning after the election I made three batches of soup. And then, on the back of a piece of scratch paper, I wrote a poem.

I did all this before thinking. I did this as immediate coping. I had not slept well, had had nightmares, the kind many of us are continuing to have, maybe will keep having. And I was hung over, fuzzy headed. Like many of us, I’d been drinking too much in the weeks leading up to the vote. Like many of us, I’d been drinking through it.

In the morning, my first thought was of anger and hurt but also of needing to work and work hard. Of needing to clean house. I know myself well: I know that even though Descartes says “I think therefore I am” I myself can’t think until I build up the very base of my being. I am, yes, but I have to work to think, and I know that my body frames my thought: My mind is securely lodged in my body. My body doesn’t work unless I feed it.

That morning, even before the coffee was made, I had the broth and the sweet potatoes and the quinoa on the table. I shredded the chicken scraps. I went out in the cold air and picked our chard. I washed it. I smashed up garlic. The kids weren’t up yet. Hitting the board felt good. The board held my anger. I wanted to make the biggest meal possible out of all the odds and ends we had around the house. And I wanted the dirt on my fingers. I wanted to feel that even if the world might be collapsing inward on some angry toxic axis of hatred, there would still be people working to feed other people and that I would be one of them.

I cook because it helps me think not with my mind but with my hands, my body, my grief. I cook because you can gather the food and lay it out and prepare it and make do with what you have—water, salt, bones, a few dry potatoes, whatever survived the rain— and then you can move around the kitchen and in a few hours have something real: a meal, which can be served at a table, at which people can gather themselves. Cooking is cheap pleasure with high rewards. You can pass time making something everyone needs: food.

Cooking, when done right, is unfussy, steadying, and necessarily hopeful—it imitates and partakes in the efforts of making art but promises something immediately tangible—a meal, a gift, a jar of jam, some cake. You can make something out of even your lemon rinds. You can give what you made to someone and it will make their life better too. I love my poems, but I have to be honest: I cannot always say that of my poems.

I loved the cold feel of dirt on my hands that morning. It was sobering to be at the level of osmosis and humus and clay, of the minerals that we are made of and which will outlast us— even if we are destroying our own time on the planet. These are the minerals we will each one day become, maybe sooner than we wish. I was grateful again that the chard seemed to be going on getting bushy despite the blistering idiot who may now take power and the raw rotten stink of hate on the table of this broken America.

I was grateful to be in my body, to have a body.

I cook because I commit again to belonging to the gathering I hope for. I commit to the idea of nourishing and being nourished and coming to the big table. And I commit to being part of a chain of interdependence, one that says “because others are, I am, and because I am, I can think and work and pray.” Food reminds me that I am not alone: none of us is alone. Because none of us is only ourselves, we are our food and the planet that grew it. We are sunlight and soil. And we are not mere demographies or representations: we are real. Each of our bodies can build a house or feed a body or stage a protest or sing a song.

That morning I chopped potatoes, and I didn’t think exactly. But what I think my body was trying to craft even then was not just soup but hope: hope not only that we all be fed, but also that the hands building the meal might also build a poem, a room, more justice. My hands were telling me as I chopped not to despair. I believe in food. I believe in art. I heard my knife hitting and hitting the board.

Tess Taylor’s chapbook, The Misremembered World, was selected by Eavan Boland for the Poetry Society of America’s inaugural chapbook fellowship. The San Francisco Chronicle called her first book, The Forage House, “stunning” and it was a finalist for the Believer Poetry Award. Her second book is Work & Days, which Stephen Burt called “our moment’s Georgic.” Her work has appeared in The Atlantic, Boston Review, Harvard Review, The Times Literary Supplement, and other places. Taylor chairs the poetry committee of the National Book Critics Circle, is currently the on-air poetry reviewer for NPR’s All Things Considered, and was most recently visiting professor of English and creative writing at Whittier College. Taylor has received awards and fellowships from MacDowell, Headlands Center for the Arts, and The International Center for Jefferson Studies. Taylor recently was awarded a Fulbright US Scholar Award to study and lecture at Queen’s University Belfast, in Northern Ireland, for six months in 2017.

Tess Taylor’s chapbook, The Misremembered World, was selected by Eavan Boland for the Poetry Society of America’s inaugural chapbook fellowship. The San Francisco Chronicle called her first book, The Forage House, “stunning” and it was a finalist for the Believer Poetry Award. Her second book is Work & Days, which Stephen Burt called “our moment’s Georgic.” Her work has appeared in The Atlantic, Boston Review, Harvard Review, The Times Literary Supplement, and other places. Taylor chairs the poetry committee of the National Book Critics Circle, is currently the on-air poetry reviewer for NPR’s All Things Considered, and was most recently visiting professor of English and creative writing at Whittier College. Taylor has received awards and fellowships from MacDowell, Headlands Center for the Arts, and The International Center for Jefferson Studies. Taylor recently was awarded a Fulbright US Scholar Award to study and lecture at Queen’s University Belfast, in Northern Ireland, for six months in 2017.

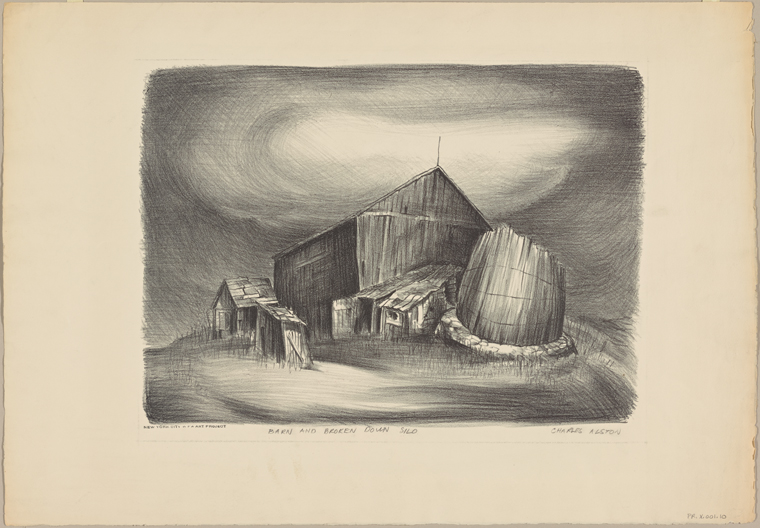

featured image via Marjan Lazarevski on Flickr.

Fabrice Poussin teaches French and English at Shorter University. Author of novels and poetry, his work has appeared in Kestrel, Symposium, The Chimes, and dozens of other magazines. His photography has been published in The Front Porch Review, the San Pedro River Review and more than 170 other publications.

Fabrice Poussin teaches French and English at Shorter University. Author of novels and poetry, his work has appeared in Kestrel, Symposium, The Chimes, and dozens of other magazines. His photography has been published in The Front Porch Review, the San Pedro River Review and more than 170 other publications.

Justin Marks’ books are,

Justin Marks’ books are,

Leah Umansky’s The Barbarous Century is forthcoming from Eyewear Publishing in 2018. She is also the author of the dystopian-themed Straight Away the Emptied World (Kattywompus Press, 2016), the Mad-Men inspired chapbook, Don Dreams and I Dream (Kattywompus Press, 2014), and the full length, Domestic Uncertainties (BlazeVOX, 2012). Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in POETRY, Boston Review, The Journal, and Thrush Poetry Journal. She is a graduate of the MFA Program in Poetry at Sarah Lawrence College and teaches middle and high school English in New York City. More at

Leah Umansky’s The Barbarous Century is forthcoming from Eyewear Publishing in 2018. She is also the author of the dystopian-themed Straight Away the Emptied World (Kattywompus Press, 2016), the Mad-Men inspired chapbook, Don Dreams and I Dream (Kattywompus Press, 2014), and the full length, Domestic Uncertainties (BlazeVOX, 2012). Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in POETRY, Boston Review, The Journal, and Thrush Poetry Journal. She is a graduate of the MFA Program in Poetry at Sarah Lawrence College and teaches middle and high school English in New York City. More at

Tess Taylor’s chapbook, The Misremembered World, was selected by Eavan Boland for the Poetry Society of America’s inaugural chapbook fellowship. The San Francisco Chronicle called her first book, The Forage House, “stunning” and it was a finalist for the Believer Poetry Award. Her second book is Work & Days, which Stephen Burt called “our moment’s Georgic.” Her work has appeared in The Atlantic, Boston Review, Harvard Review, The Times Literary Supplement, and other places. Taylor chairs the poetry committee of the National Book Critics Circle, is currently the on-air poetry reviewer for NPR’s All Things Considered, and was most recently visiting professor of English and creative writing at Whittier College. Taylor has received awards and fellowships from MacDowell, Headlands Center for the Arts, and The International Center for Jefferson Studies. Taylor recently was awarded a Fulbright US Scholar Award to study and lecture at Queen’s University Belfast, in Northern Ireland, for six months in 2017.

Tess Taylor’s chapbook, The Misremembered World, was selected by Eavan Boland for the Poetry Society of America’s inaugural chapbook fellowship. The San Francisco Chronicle called her first book, The Forage House, “stunning” and it was a finalist for the Believer Poetry Award. Her second book is Work & Days, which Stephen Burt called “our moment’s Georgic.” Her work has appeared in The Atlantic, Boston Review, Harvard Review, The Times Literary Supplement, and other places. Taylor chairs the poetry committee of the National Book Critics Circle, is currently the on-air poetry reviewer for NPR’s All Things Considered, and was most recently visiting professor of English and creative writing at Whittier College. Taylor has received awards and fellowships from MacDowell, Headlands Center for the Arts, and The International Center for Jefferson Studies. Taylor recently was awarded a Fulbright US Scholar Award to study and lecture at Queen’s University Belfast, in Northern Ireland, for six months in 2017.