I was an earthy kid. I had no compunction about draining dregs from beer cans thrown into the ditch near my kindergarten bus stop. On warm days, I loved to kneel and feel the gritty, hot asphalt dig into my knees as I scraped the tough air-dried layer off an oozing bubblegum wad that someone had spit out. Once past the top layer, the gum would still be day-glo pink, green, or purple and emit a most luscious aroma. Sour green apple was my favorite.

Five was a rough year. My mother died of brain cancer the same month (January) my legs had been locked into braces to keep me from walking pigeon-toed. It was the year my kindergarten teacher tied down my left hand to keep me from becoming the “spawn of Satan.” Daddy was a state representative, away from home Monday through Thursday in Jefferson City. His small salary meant hiring the cheapest caretaker he could find. Perhaps you can forgive a girl some of the sensory eccentricities that punctuated her early life.

Because the truth of it was, my reality was miserable, save for fleeting magical weekends when Daddy was my own. Weekends when my sister and I would accompany Daddy on his date night over to Cathy Miller’s where we could try out Cathy’s array of false eyelashes, lipsticks, and eyeshadows. It meant falling asleep on Cathy’s Barcalounger while watching soft gobs in the blue-green lava lamp float up and sink down. But most of all, it meant utterly delicious, fun food.

Cathy often indulged us with fondue. We sat cross-legged on her shag carpet in front of the fireplace while we dipped hot dog chunks, bread cubes, asparagus spears, and fat button mushrooms into the fondue pot’s boiling oil, listening to Lou Rawls croon on the eight-track. Or, if not fondue, it would be Daddy bringing over filet mignon to grill out on Cathy’s tiny deck, sometimes even allowing me to eat the bacon off his, when they came sizzling off the grill. Or his newest creation: a fat minced steak patty “doctored up” with Lawry’s Seasoning Salt, perched on an English muffin half. Once the patties registered medium rare under the broiler, Daddy removed the pan and covered the patties with thick beefsteak tomato slices and crowned them with liberal dollops of Marie’s Blue Cheese Salad Dressing. Five more minutes, and the patties emerged as works of art, bubbling, oozing, juicy, with the English muffin sponging up all that glorious fat. Whatever was on the menu, it was delicious, and not only would we have a fantastic dinner with Cathy, but we would also have Saturday lunch and Sunday breakfast before the reality returned Sunday afternoon in the form of our houskeeper-nanny-cook, Dorothy.

The patties emerged as works of art, bubbling, oozing, juicy, with the English muffin sponging up all that glorious fat.

It was around age ten that I became scared of Dorothy, who took care of my sister and me during the week. I became increasingly disgusted with her, even with my love of beer dregs and the aroma of discarded gum. From a child’s eyes, she was the incarnation of Roald Dahl’s Mrs. Twit. Wiry, greasy, salt-and-pepper hair, a twitching mouth and constantly dripping nose, a dirty bra strap hanging perpetually over her ham hock arm, a fanny that hung over the sides of the kitchen table chairs, a voice that sounded like she ate gravel, and worst of all, an utter lack of skills in the culinary department made Dorothy our daily nightmare.

Sometimes, starvation was better than eating what Dorothy cooked. I dreaded her fried whiting. When I chose this golden brown, flaky gorgeous white fish and a side of baked macaroni and cheese at the Forum Cafeteria after church on Sunday, the meal convinced me that there was a God in heaven. But when confronted with the same dish from Dorothy? It left me identifying with Job and his travails as God and Satan subjected the poor man to a game of faith. Dorothy’s rendition of fried whiting was riddled with bones that stuck in my throat as I tried to get it down, usually burned on one side and raw on the other, and always swimming in a puddle of rancid bacon fat. Inevitably, the burned-raw whiting would be served with my least favorite accompaniment of all, canned peas.

I had few memories of my beloved mother, but sadly the most prominent involved a day when I was around four years old, perched on the kitchen stepping stool and helping Mother cook. She opened a can of peas, and floating lazily on top of the brine was a dead mayfly. The horror of peering at that bloated, drowned insect resulted in immediate nausea. After that, the thought of canned peas made the bile and acid rise up in my throat. Thank goodness for our dachshund Bismarck, stationed as a sentinel underneath the dinner table, eagerly awaiting scraps. With a great show of politeness, I would spoon up a mouthful of Dorothy’s fish along with it some of the puke-colored peas, tip it into my mouth and appear to chew. I would then take my napkin, carefully empty the whole mess from my mouth into it, and take it to my lap where said peas and fish emptied onto the floor and down Bismarck’s gullet. Yes, I would go to bed hungry, but at least I had my insides intact.

It left me identifying with Job and his travails as God and Satan subjected the poor man to a game of faith.

In Dorothy’s culinary repertoire there was one dish that I could tolerate and if hungry enough, find the wherewithal to actually enjoy: chili. Because it could be thrown together quickly and left to simmer, she made it often, given that her main activity was watching reruns of the Beverly Hillbillies, I Love Lucy, the Dick Van Dyke Show, Green Acres, and Petticoat Junction on Channel 41 while embroidering and eating a candy-like dietary supplement known as Ayds. Throwing a pound of hamburger in the aluminum stockpot, browning it with some sliced onion, adding a can of kidney beans, a couple of cans of tomatoes, and a packet of Williams Chili Seasoning was all there was to it, then back to the La-Z-boy until supper time.

One late afternoon, Dorothy and I found ourselves in an unusually social mood after the ending of Petticoat Junction put us both in good spirits. At any rate, I found myself in the kitchen with Dorothy as she began the process of making chili, asking her if she would show me how it was done. I was still small enough physically that I needed to stand on that same footstool that my mother had used when we opened the can of peas with the dead mayfly. Taking my post, Dorothy showed me how to brown the hamburger, as she nibbled it raw from time to time, how to use all the grease from the hamburger to soften the onion, how to add the Williams Chili Seasoning, which in turn soaked up a lot of the grease, and how to add the cans of beans and tomatoes. I was hungry watching her work, as the pot started to simmer. The pools of remaining grease coalesced on top like an oil slick, and the aroma started to waft through the air.

Then, Dorothy got some chili seasoning up her nose and let out a gigantic sneeze, reaching at the same time for her well-used Kleenex knotted up in her bra shelf where she always kept it. The sneeze caused her to fumble her hold on the Kleenex, just as Bismarck came trotting into the kitchen, causing Dorothy to unwittingly drop the Kleenex into the chili. She kept on stirring with no thought to anything other than the dachshund. The Kleenex got caught in the whirlpool of the motion, sinking out of sight into the depths of the chili and then like a drowning man trying to save himself, popped up to the top of the pot before being dragged down again to the bottom.

I found myself in the kitchen with Dorothy as she began the process of making chili, asking her if she would show me how it was done.

In horror and disgust, I shouted out, “Dorothy! You dropped your Kleenex into the chili!” I was devastated that we would have to throw out the pot and start again, or—God forbid—have to eat the week-old pork chops burned on one side and raw on the other that were lodged in the refrigerator. Startled by my shout, Dorothy turned her attention back to the stove, scooped up the now disintegrating Kleenex and quickly plucked it off the spoon, throwing it, dripping grease and tomato sauce along the way, into the trash.

“No harm done,” she muttered as she continued to stir.

Oh dear lord! Suddenly, even the week-old burned-raw pork chop moldering in the refrigerator seemed appetizing. Feeling like I was going to be sick, I jumped off the stool and ran upstairs to my bedroom.

I sat on my bed holding my stomach, trying to imagine sitting down to supper as if nothing was wrong. Leah was nowhere to be found, or I would have shared my information with her.

Soon enough, it was time for supper. Dorothy liked to organize the meal so that we could watch Bowling for Dollars, which was a huge favorite for all of us.

“Andrea! Leah!” she bellowed. “Time to eat!” Knowing that I had no choice but to go downstairs, and also knowing that if I protested the unsanitary nature of the meal, she would force me to eat two portions as punishment for being too “bloody fine-mouthed,” I started my journey down the hallway. I decided that my only option was to feign the flu. I would enter the kitchen doubled over and complaining of a severe tummy ache.

I came down the stairs and entered the kitchen to see the sleeve of saltines on the table and Dorothy ladling the dinner into our decorative Parkay margarine bowls that we usually ate out of. Leah was already at the table turning on the television.

“Dorothy,” I moaned, clutching my stomach and doing the most important acting job of my young life. “I’m not feeling too good! Is it okay if I skip dinner?” Hungry herself and anxious not to miss Fred Browski’s opening moment on Bowling for Dollars, Dorothy was blessedly distracted. Having entirely forgotten about the Kleenex in the chili, given that it was “no matter,” she muttered, “What’s wrong? You eat a bunch of candy after school? Go on upstairs, and I’ll be up in a while to give you some medicine.” Relieved but anguished that my poor sister, Leah, was going to ingest that chili, I turned from the table and made my way upstairs.

'Dorothy's Chili' is The Inquisitive Eater's Essay of the Month for March 2018.

Andrea Broomfield, Ph.D., is Professor of English at Johnson County Community College in Overland Park, Kansas, USA. She is author of Food and Cooking in Victorian England: A History, and Kansas City: A Food Biography. She is currently at work on a new book, “The Atlantic Celts: A Gastronomic Memoir from Ireland to Iberia” with co-author, Beebe Bahrami. This is Andrea’s first foray into creative nonfiction.

Andrea Broomfield, Ph.D., is Professor of English at Johnson County Community College in Overland Park, Kansas, USA. She is author of Food and Cooking in Victorian England: A History, and Kansas City: A Food Biography. She is currently at work on a new book, “The Atlantic Celts: A Gastronomic Memoir from Ireland to Iberia” with co-author, Beebe Bahrami. This is Andrea’s first foray into creative nonfiction.

Featured image via Flickr.

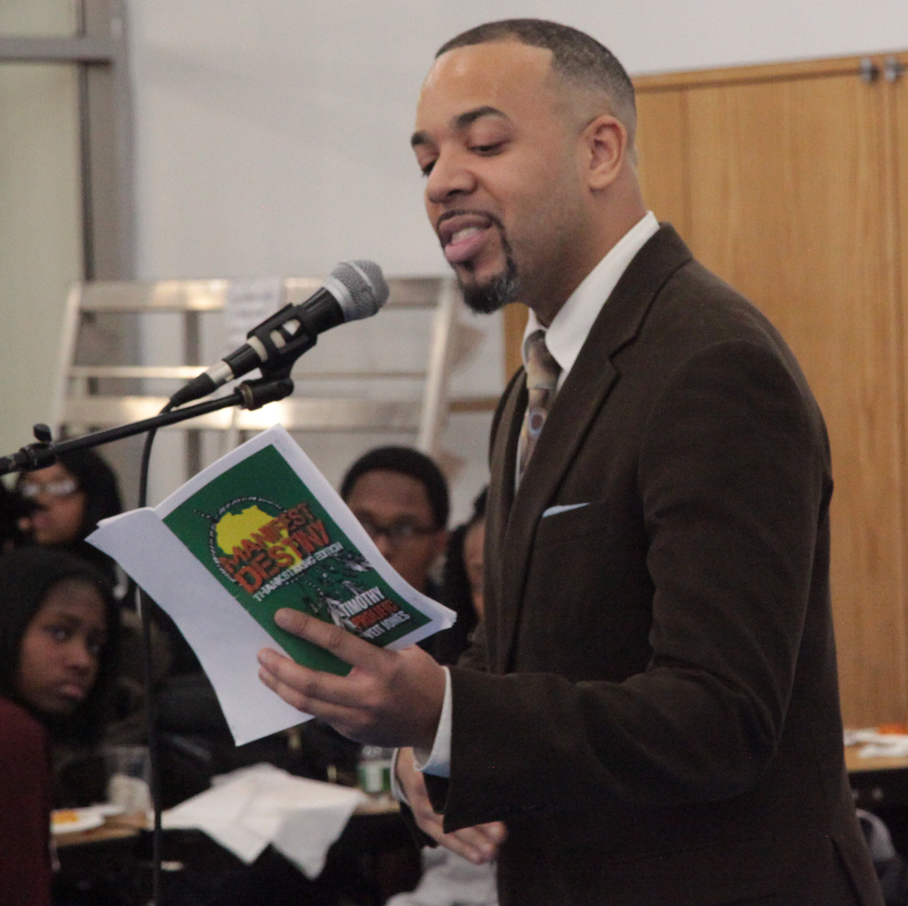

Timothy Prolific Veit Jones a poet, educator, and organizer whose creative work operates in the continuum of the Black Arts Movement, using a multi-disciplinary approach rooted in Hip-Hop culture as an African Diasporic folkloric praxis. He has performed his poetry at a diverse variety of venues, from Cornell University to Rikers Island to STooPS in Bed-Stuy. He has been published in African Voices, 12th Street, the graphic novel Gunplay, the Penmanship Book anthology 30/30 Vol. 2, The Ferguson Moment, and YRB Magazine. Through his former publishing company, Andre Maurice Press/Indelible Books, he edited and released Blackout Arts Collective’s One Mic: A Lyrics on Lockdown Anthology and Peuo Tuy’s Khmer Girl. Tim was a Riggio Fellow at The New School, and is a fellow at The Watering Hole. He is the author of Musaic: 40 Days, 40 Nights and the forthcoming ethnographic book of poetry titled Water + Blood. Timothy is the Visioning Partner (VP) for Institutional Culture at PURPOSE Productions, teaches Kuumba/Integrated Arts at Ember Charter Schools, and is the co-founder of the Rebel Waters publishing and performance collaborative. He is from Uniondale (Long Island), and lives in Bed-Stuy.

Timothy Prolific Veit Jones a poet, educator, and organizer whose creative work operates in the continuum of the Black Arts Movement, using a multi-disciplinary approach rooted in Hip-Hop culture as an African Diasporic folkloric praxis. He has performed his poetry at a diverse variety of venues, from Cornell University to Rikers Island to STooPS in Bed-Stuy. He has been published in African Voices, 12th Street, the graphic novel Gunplay, the Penmanship Book anthology 30/30 Vol. 2, The Ferguson Moment, and YRB Magazine. Through his former publishing company, Andre Maurice Press/Indelible Books, he edited and released Blackout Arts Collective’s One Mic: A Lyrics on Lockdown Anthology and Peuo Tuy’s Khmer Girl. Tim was a Riggio Fellow at The New School, and is a fellow at The Watering Hole. He is the author of Musaic: 40 Days, 40 Nights and the forthcoming ethnographic book of poetry titled Water + Blood. Timothy is the Visioning Partner (VP) for Institutional Culture at PURPOSE Productions, teaches Kuumba/Integrated Arts at Ember Charter Schools, and is the co-founder of the Rebel Waters publishing and performance collaborative. He is from Uniondale (Long Island), and lives in Bed-Stuy.

Bridget Kiley is a writer and editor based in NYC by way of Vermont. She is a graduate of The New School MFA program in creative nonfiction. Her other work can be found on Fjords Review, The Culture Trip, The New School Blog, and more. Follow her on Twitter

Bridget Kiley is a writer and editor based in NYC by way of Vermont. She is a graduate of The New School MFA program in creative nonfiction. Her other work can be found on Fjords Review, The Culture Trip, The New School Blog, and more. Follow her on Twitter

Leah Iannone received her MFA from The New School’s Creative Writing Program. She currently works as a director of academic planning. Her work has appeared in Newsweek, 12th Street, The Best American Poetry Blog, Alimentum, Redheaded Stepchild, PAX Americana, Barrow Street, Psychic Meatloaf, and The Inquisitive Eater.

Leah Iannone received her MFA from The New School’s Creative Writing Program. She currently works as a director of academic planning. Her work has appeared in Newsweek, 12th Street, The Best American Poetry Blog, Alimentum, Redheaded Stepchild, PAX Americana, Barrow Street, Psychic Meatloaf, and The Inquisitive Eater.

Liz von Klemperer is a Brooklyn based writer and succulent fosterer. Her reviews have appeared in Electric Literature, The Rumpus, Lambda Literary, and beyond. Find more at lizvk.com.

Liz von Klemperer is a Brooklyn based writer and succulent fosterer. Her reviews have appeared in Electric Literature, The Rumpus, Lambda Literary, and beyond. Find more at lizvk.com.

Sarah Renee Beach received an MFA in Poetry from The New School where she was a reader for LIT. Follow her on twitter

Sarah Renee Beach received an MFA in Poetry from The New School where she was a reader for LIT. Follow her on twitter