By Fabio Parasecoli, Associate professor and coordinator of food studies, The New School.

For a few days, Bogotá turned into the South American capital of food design. The second annual meeting of the Red Latinoamericana de Food Design (the Latin American network of food design) took place at the Industrial Taylor, a state-of-the-art food business facility, from October 20th to the 24th, under the auspices of the Universidad Nacional and the Universidad de los Andes. The opportunity allowed scholars and professionals from countries as diverse as Mexico, Colombia, Uruguay, Argentina, and Brazil to gather and discuss the present and future of their field.

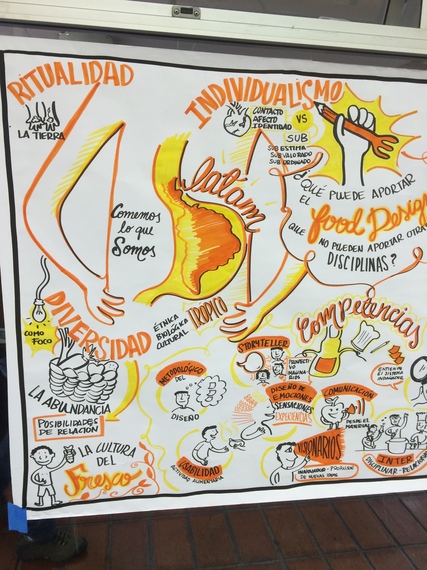

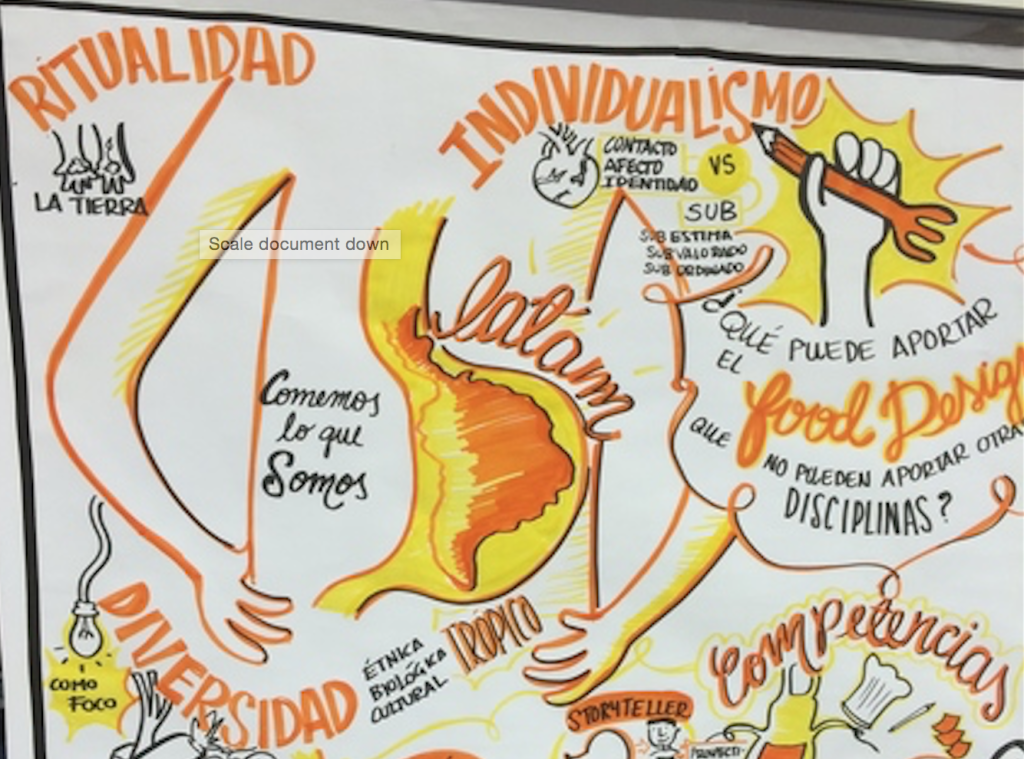

One of the main goals of the meeting, which was structured in a two-day seminar about pedagogy and a live-streamed series of public talks and debates, was to identify the characteristics of food design in Latin America in terms of themes, approaches, and stakes. Many participants were experts in industrial, product, and packaging design, while others focused on the impact of design in the kitchen and on all kinds of creativity processes connected to food. I will discuss the conversations about how and why to teach food design in an upcoming post. For now, I will focus on what emerged as very urgent topics: To what extent is food design relevant in Latin America, with all its dazzling variety of cultures, populations, and complicated histories? What does it mean to be a food designer in that region? What unique peculiarities shape food design, its practice, and its theoretical exploration in Brazil, Mexico, or Colombia?

The discussion was spirited, emotional, and at times anarchical, allowing all the participants to contribute their point of view. One of the elements that surfaced was the influence of natural, human, and political diversity on the work of food designers. Colombia and Brazil, for example, boast the most impressive biodiversity on Earth, and both have large native populations that maintain traditional knowledge of plants, animals, and culinary techniques that are only partially known outside their communities. Reference was made to the culture of “fresco”, all that is fresh and ready to be gathered and enjoyed. This staggering abundance clashes with issues of malnutrition, discrimination, and oppression, while highlighting opportunities for building new kinds of relationships around food and its rituals.

The scars left by centuries of colonialism and the struggles for independence, followed by decades where projects of national construction were highjacked by violence and political turmoil, have left a heritage that participants variously indicated as “lack of self esteem”, “subordination,” and “doubts about one’s value.” At any moment, this painful baggage risks hindering cultural and social advancement. However, the citizens of South American countries seem to have recourse to an inordinate amount of vitality and creativity, which tends to express itself in forms of extreme individualism and suspicion of politics. At the same time, solidarity and a shared sense of community often counteract these tendencies toward fragmentation. Everybody admitted to the fact that Latin America is a place of blatant contradictions, which nevertheless can constitute powerful engines for transformation.

These promises and ambiguities cannot but deeply shape the work of any designer, and in particular food designers. They are called not only to have people reflect on their relationship to food and its consumption, but also to introduce change to make food production and distribution systems more equitable, efficient, and sustainable, balancing technological innovation with community needs and cultural priorities. It is a very tall order, but the enthusiasm was palpable, especially among young up-and-coming designers, both still in school and already working. Latin America has a good chance of becoming a powerhouse in food design, in radically different ways from what we see in North America and Europe.

Comments are closed.