from Huffington Post

by Fabio Parasecoli

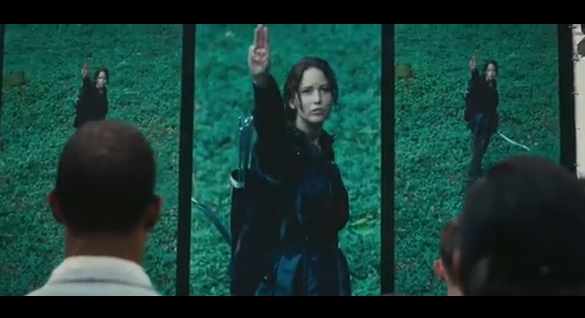

The media, and fans all over the world, are abuzz with excitement about The Hunger Games, the movie based on Suzanne Collins’ novel, the first within a trilogy with the same name. No need for a spoiler alert: It is the story of a young woman, Katniss Everdeen, who has grown up struggling to provide food for herself and her family in a future, war-torn and battered United States. The events unfold in a nightmarish future in which a tyrannical Capital has imposed its dominion over the rest of the country. Katniss is constantly faced with scarcity of food: The provisions allotted by the Capital are far from sufficient, and many families opt to buy rations of food in exchange to increase their chances to get picked to participate in the sadistic fight-to-the-death Hunger Games, sponsored by the Capital. The competition takes place in an artificial arena dotted with forests and meadows, lakes, streams, and hills, and only one contestant is allowed to come out alive. Katniss finds herself forced to fight for survival, hunting, scavenging, gathering roots and berries, destroying her opponents’ food reserves and, yes, killing.

As any powerful literary dystopia, the book is a reflection not on the future, but on our present. Good science fiction, after all, reminds us that the world we inhabit could have been different, and could still be different. It manages to bring us to temporarily suspend our disbelief, creating worlds that are credible enough to grant us a sense of uncomfortable familiarity. To achieve these effects, sci-fi has often employed food and eating, forcing us to reflect on their relevance for the stability of political and social structures. In the post-disaster America that Katniss inhabits, food is a source of power, the oil that allows the administrative machine to function. Individuals have limited choices: All is decided somewhere else. That is, unless citizens decide to break the rules: Katniss poaches for game in places where she’s not supposed to roam, strategically uses provisions to secure her victory in the arena, and even manages to use food to force her will on the omnipotent authorities.

Katniss’ epic adventures remind us of another great dystopian novel, Octavia Butler’s The Parable of the Sower, which I discuss in my book, Bite Me: Food in Popular Culture. Also in Butler’s novel, society collapses on itself because of greed and social unrest. America breaks down into independent gated communities under constant siege from those less fortunate, trying to get their share of wealth and, of course, food. The story is narrated by Lauren Olamina, a young woman who, like the other families in the compound where she lives, tries to make up for the lack of food by growing fruit and vegetables. It is a difficult task for suburbanites, used to buying products from supermarkets; they need to learn from scratch what can be grown in orchards or backyards, and the fruit of their labor is under constant threat from thieves and hungry marauders. With the political body crumbling down, extreme consumerism and the free market show their ugly side, hitting the weakest portions of society while causing scarcity of food and, later, hunger. Food is the only hope for survival and seeds are the promise of future crops. When Lauren’s community is finally invaded, the young girl is as equally affected by the sight of the destroyed crops as by the dead people. She starts traveling, facing the dangers of a land without rules and principles, where all that counts is survival and, consequently, securing the next meal. In Butler’s dim future, the social fabric is frayed, one against another.

In The Hunger Games, Katniss makes her mark in a world where the downtrodden devise tactics to survive in a land controlled by others. We are reminded that when we enter a supermarket, or decide instead to go to a farmers’ market, or join a Community Sustained Project, we enjoy the illusion that we are making choices for ourselves, expressing our own taste and personality. In reality, all available options are pre-determined and pre-packaged by production constraints, political choices, and structural dynamics. In a consumer society where alternative food networks and associations have been built on the premise that we can change the food system one meal at the time and that eating is an agricultural act, Katniss’ adventures remind us that, after all, we are poachers in somebody else’s territory. We cannot always win by fighting in the limited arena we are familiar with; we need to figure out ways to change the whole system outside the arena.

1 Comment

Hunger Games- related food for thought from someone whose diet more closely tracks that of Haymitch than Katniss:

http://charleneoldham.com/2012/03/22/the-hunger-games-supersized/