by Kathryn Tomajan

I find the magazine shoved into my mailbox, and the first thing I notice is the image on the back cover: a gorgeous, perfect bowl of ramen. While studying food culture in Italy, I received a gift subscription to Lucky Peach magazine, the latest project from celebrity chef and New York restauranteur David Chang. I’ve been in Italy for three months and my craving for spicy Asian food is off the charts. Looking at the photo is torturous.

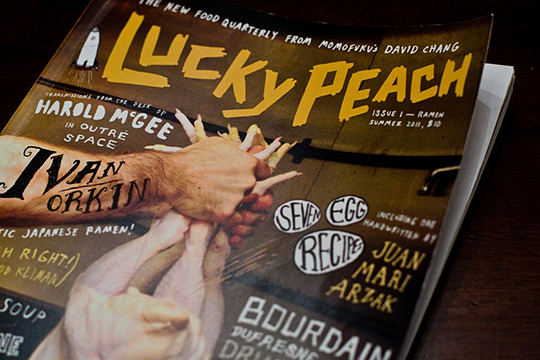

I pass it around to some of my classmates –not unlike sex-deprived teenage boys might pass around a single copy of Hustler– and we all groan at the sight of noodles, nori and runny egg yolk. But the lust-inducing recipes and raw nudity on the cover (ok, maybe naked chickens don’t count) is where the porn comparisons end. It is a food magazine, but not like one you’ve seen before. This one’s from the cool kids, the bad boy of the culinary world, indie publishing darling McSweeney’s and star contributors like Anthony Bourdain, Harold McGee and Ruth Reichl.

At worst, Lucky Peach is a piece of pop culture created to stroke the egos of its narcissistic creators and encourage the god-like worship of chefs. At best, it’s a high-caliber literary work from creative food professionals doing cool things with their friends. Either way you look at it, the magazine is created in the image of its makers –unruly, testosterone-driven, egotistical, inventive and obsessive. And ultimately it’s the makers, not the food, on display in Lucky Peach.

In the era of dying print publications, Lucky Peach is a 175-page publication without a single ad. (Well, actually there are two ads: one for the Lucky Peach iPad app that is still in development, and one for a McSweeney’s cookbook.) Each quarterly issue will have a theme and the first is spot on with the hippest food trend: ramen.

Lucky Peach isn’t for your average food media audience who dog-ear recipes while making grocery lists. The magazine is written in an ultra-casual tone with a more than healthy dose of profanity, slang and restaurant jargon. Its target is hard-core foodies –the kind that go to underground supper clubs, already know that ramen is the new cupcake, and hate the term foodie. At $10 a pop, it’s pricey. Readers get a physically superior magazine with heavy matte paper and exceptional design. Readers also get a glimpse into an exclusive culinary clique.

The opening article is a travelogue of Chang and fellow editor Peter Meehan’s ramen research trip to Japan. The 16-page spread documents the drunken ramen binge interspersed with noodle-praising expletives, the idol worship of Toyko’s master ramen chefs and two accounts of Chang vomiting from overindulgence.

In one of only two pieces by women, Ruth Reichl reports on her instant ramen taste test. In a maternal tone, Reichl insists on tossing the ramen packet. “Throw out the packaged soup mix. Trust me… This is not something you want to eat.” Yet turn the page and naughty chef Chang uses that disgusting seasoning packet in a series of instant ramen recipes including potato chip dip and a riff on the Italian classic cacio e pepe.

This use of a lowbrow ingredient is not for the sake of irony. In another article, the ingredient-driven cuisine popularized by Alice Waters –who is not a formally trained chef– is lambasted in a rambling conversation on mediocrity between Chang, Bourdain and fellow New York chef Wylie Dufresne:

Wylie: Ingredient-driven food, what the fuck does that mean?

Anthony: Okay, it means taking three or four pretty good ingredients or very good ingredients or superb ingredients and doing as little as possible-

Wylie: It’s called cooking… That farm to table bullshit… Come on. There’s just too much of it.

Anthony: Farm to table is saying right up front that it is —to use the dreaded phrase— ingredient-driven rather than chef-creativity-driven or technique-driven. It’s saying that the most important thing is where it comes from, how it was grown, who grew it, and not what you do with it. It’s basically patting yourself on the back for being there.

Wylie: But that’s not cooking. We’re talking about cooking. We are cooks. We should have a responsibility to cook. The fact that we’re talking about ingredients rather than what people are doing with the ingredients is a mistake. Do something to it. That’s showing that you have skill.

Dufresne’s diatribe on farm-to-table cuisine justifies his existence. His conclusion that ingredients are secondary to the golden touch of a skilled cook secures he and his buddies’ position as the Creators in the food universe.

The recipes in Lucky Peach echo that attitude. Heavy on technique, they require a high level of kitchen skills and are probably not for the average home cook. For example, in the introduction to one recipe Chang writes:

This recipe is not for a final dish, or something I’d put on a menu, or something that’s been fully optimized for home cooking. What it is is a blueprint for making a tonkotsu-ish broth in a short period of time—it’s more about the principle than the technique. In this case, we use a pressure cooker to extract a ton of flavor out of the bones quickly, but pressure-cooking the stock for too long also clarifies it. So this is a hybrid method, cooked partially under pressure.

Readers are privy to the ramen broth recipe from Chang’s Michelin-starred restaurant Momofuku, a guide to fresh alkaline noodles, and approximately 20 ways to cook an egg with a full-spread chart to illustrate yolk texture.

We also find more classic food writing such as a regional guide to ramen in Japan, a review of “the best potato chips in the world” and an insightful article on authenticity. And there’s some unusual elements for a food magazine –a work of fiction by Japanese novelist Jun’ichirō Tanizaki, illustrations by award-winning cartoonist Tony Millionaire, and full-page renderings of now-legendary ramen chefs reproduced from letterpress prints– quality art and literature by anyone’s standards. Even if we never attempt a single recipe printed in Lucky Peach, we must assume they’re works of art since they’re housed in the same gallery.

No doubt Lucky Peach is fuel for the food and food celebrity obsessed. In the first issue, ramen is fetishized but it’s also analyzed, deconstructed and re-imagined. It elevates food to art, chefs to artists, and cooking to a creative process. It doesn’t make the food or its creators more accessible to us, but maybe that’s the point. Not everyone can cook, but lucky for us there are some chefs in this world that can.

Kathryn Tomajan is studying food culture at the University of Gastronomic Sciences in Pollenzo, Italy. She is also a co-founder of Eat Retreat, a creative workshop for leaders in the food community.

2 Comments

GREAT article!

Pingback: Thank You For A Fabulous 2012! | The Inquisitive Eater