One of the most ancient scriptures in Hinduism, the Brahmanda Purana, is named after an egg. It was all there was, in the beginning: the Brahmanda, the egg where Brahma, the creator, and Brahman, the ultimate cause and effect of the universe, first swirled around together before the shell broke and the contents burst forth to make the world. (While anda in Sanskrit has been translated many ways, including “seed,” “womb,” and “universe,” it still means “egg” in Hindi, Urdu, and Nepali.)

This isn’t the only cosmogony built around the concept now known as the “cosmic egg.” In the Hellenistic world, followers of the cryptic Orphic religion believed that Phanes (the ur-deity and creator of life) was born from a silver egg. The Polynesian creator, Ta’aroa, spent the beginning of time in an egg—until he got bored and broke out, ground up the shell to create rocks, sand, and soil, and rent his own body to create everything else. The original peoples of Finland and Estonia believed a goldeneye duck laid an egg in the sea, and when it cracked, our world was made. According to the Kalevala, Finland’s national epic: From the white part come the moonbeams / From the yellow part the sunshine.

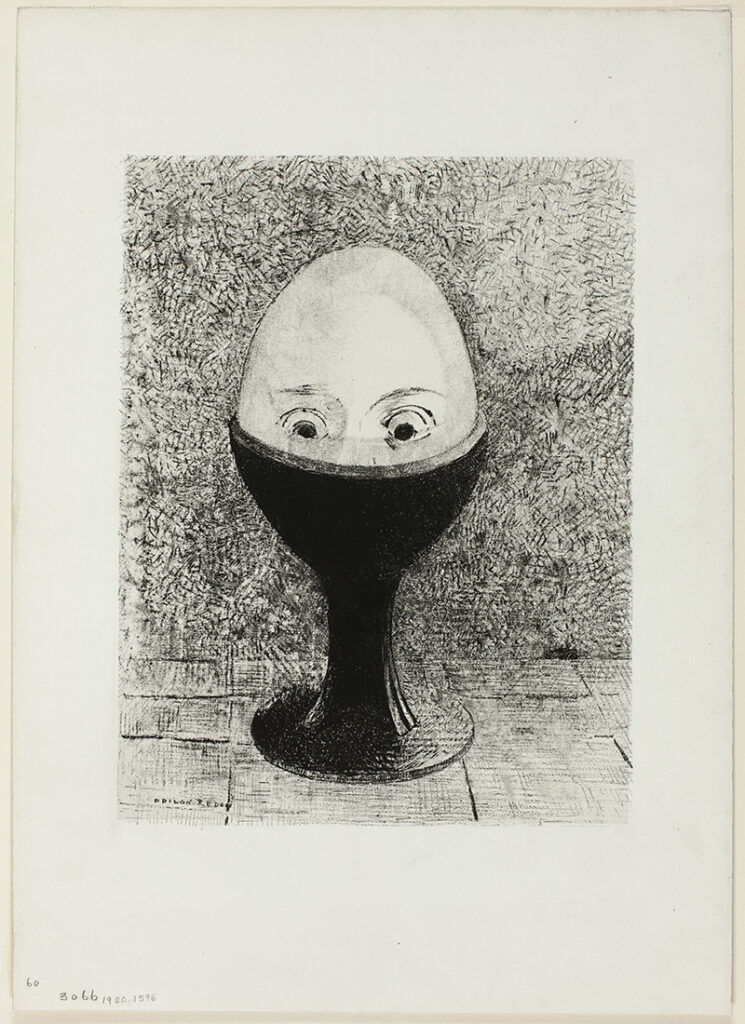

Why an egg? There’s the obvious answer: things are born from eggs. An egg contains everything a growing creature needs, an impossible, miniature, life-creating machine. But an egg is also unknowable. (M.F.K. Fisher once wrote: “Probably one of the most private things in the world is an egg until it is broken.”) We cannot see what goes on inside, can hardly decipher how what was once just fluid becomes feathers or scales. We famously cannot know whether a farm-fresh egg contains a golden yolk, or on a lucky day, two—or on an unlucky day, a half-formed chick suddenly looking back at you from the pan.

But behind its forbidding exterior, the egg does something else that’s nearly impossible: it contains duality in harmony, white and yolk an easy parallel for earth and sky, temporal and sacred, sun and moon, masculine and feminine, all touching and even blending if you give it a little shake. Though humans seem determined to find dualities and dichotomies in our existence, the egg shows us two things can be true at once. Whole worlds are contained within.

One food that M.F.K. Fisher described as being made with “equal parts of hunger and happiness” was a fried egg sandwich in the style of her Aunt Gwen, who would make them for her and her sister to fuel their long walks in the hills of Orange County. “Oh, deep sensuous delight!” Fisher writes, remembering “biting voluptuously into our tough, soggy, indigestible and luscious suppers.”

Nearly every cuisine on earth makes use of eggs, whether they come from chickens, ducks, quails, or emus. They’re the foundation of some of the world’s great comfort foods, struggle meals, and drunk snacks: Scotch eggs, egg curry, okonomiyaki, bacon-egg-and-cheese on a roll. There is nothing fancy about a bird egg: anyone who’s had to stretch a dollar knows the protein to price ratio is squarely in our favor. And yet, Fisher remembers, “We flourished on them, both physically and in our tenacious spirits.”

There is another kind of egg, though, one that has the luxurious reputation that comes with being (in the U.S. at least) very expensive. Fish eggs do not come in a shell; instead, they must be laid in water to maintain the protein membrane protecting the unctuous oil within. They are known as an aphrodisiac—sex made edible. But there is also something forbidden in how easily we can rupture the membrane under our teeth to release the amniotic brine inside. Maybe we relish becoming a destroyer of these very small worlds. Or maybe we know deep down that we are taking in life itself.

I will never forget the first time I ate fish roe: I can still conjure the midmorning October light, the restaurant on the Helsinki harbor with its fine crystal and large model ship at the center of the dining room, sails yellowing and rigging delicately strung. My family generally avoided things that were too beautiful or too expensive, which were frivolous at best, dangerous at worst. So I felt a nervous excitement as I scooped up the trout eggs, mother-of-pearl spoon awkward in my hand, and raised them to my mouth.

As I swirled the oily, briny throng around with my tongue, I halfway left my body and touched, for a moment, what it was like in the great before, when all of this was just an egg. And I realized that two things can be true at once—that unnecessary things could be necessary indeed.

M.F.K. Fisher once wrote to women: “Permit your disciplined inner self to relax, and think of caviar, and thick cream, and fat little pullets trotting through an oak grove rich with truffles, ‘musky, fiery, savory, mysterious.’” An egg can be elemental, but it can also be abundance. It can be hard or soft, ascetic or indulgent, unremarkable or sexy or impermeable or delicate or, in Fisher’s own words, both “indigestible and luscious.” Our world contains multitudes.

Humans have long understood the egg as a symbol of new life or life renewed: the roasted egg on the Seder table at Passover; painted eggs on the haft-sin table at Nowruz; Chinese tea eggs at Lunar New Year; plastic eggs at Easter, a Pagan rite of spring at its core, rolling around my childhood backyard. All have their own meanings, but their spelling is the same. Eggs were once forbidden to eat during Lent, and then eaten to break the fast; during this season, the observant still forgo some worldly nourishment to remember how a person can be fed spiritually—and to remember how sweet new life can be.

None of us really know how life began or how the universe came to be. But we think we have a pretty good guess, scientifically speaking. In the 1910s, an astronomer from Indiana named Vesto Slipher used spectroscopy to demonstrate that the universe was expanding outward, slowly but surely. Working backward, scientists agreed that things must have been expanding outward from somewhere. It followed that at some point, likely just over 13.8 billion years ago, nothing was moving at all. Everything—all matter, all time, all of it—existed in a singularity, essentially a very hot, very dense ball. Then, one day, it Big Banged.

The person who first formally proposed this idea was a Belgian named Georges Henri Joseph Édouard Lemaître. He was a Catholic priest—but one who wanted to use modern cosmology to better understand Creation. Lemaître spent his whole life trying to refine his ideas about the birth of the universe. His name for the singularity, that very hot, very dense place from which we all came? The Cosmic Egg.

Reader, I wish for you a year of eggs: Eggs fresh from the chicken coop at a farmhouse somewhere with no cell service. Scrambled eggs in the morning with someone new. A delicate souffle, pulled from the oven at just the right time, and the thrill of waiting to see whether it will fall. Brasserie béarnaise and homemade mayonnaise, onsen eggs with yolks that flow like molasses. Spaghetti carbonara and shaved bottarga. Deviled eggs passed around a cocktail party, hand after hand after human hand touching the tray. A small tin of caviar that you buy just for yourself and save until you really need it.

Let this be a year of Kinder eggs and malted milk eggs, yoni eggs, Easter eggs waiting to be found. An egg inside a human somewhere that will bring a new life into the world; the eggs of the thrush that guards her nest in a lonely elm in Prospect Park, watching me protectively as I walk past. The carved eggs my mother bought in Bethlehem at Christmas, 40 years ago, which scented my childhood bedroom with sweet olivewood.

This year, we can try to walk on eggshells a little bit less—risk getting egg on our face a little bit more. We can nurture good eggs and nest eggs, and occasionally put all our eggs in one basket, but not count our chickens before they hatch. Remember, you can’t make an omelet without breaking some eggs. May we all, even broken and cracked, become less private, more alive. We can try to imagine a world that is new again. And maybe we can settle that old debate for good: there’s no question, the egg came first.

A version of this piece first appeared in The Pandemic Post no. 5.

Hannah Walhout is a Brooklyn-based writer and an editor at The Inquisitive Eater: New School Food. Her writing has appeared in Electric Literature, Catapult, Off Assignment, and many other print and digital publications. Find more at hannahwalhout.com.

Comments are closed.