By Fabio Parasecoli

from Huffington Post

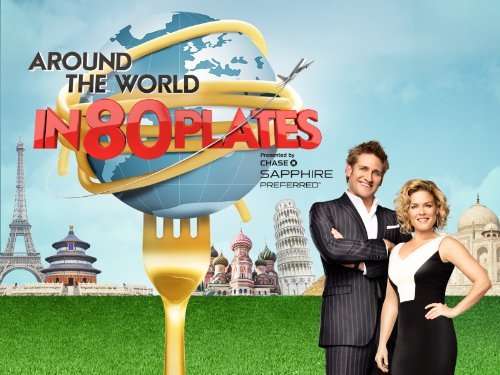

Quenelles in Lyon, tagine in Marrakesh, tortellini in Bologna: it sounds like a dream itinerary for food lovers. Moving from place to place to taste the best that the local cuisine has to offer has strong appeal. It is also the premise of a new reality show, Around The World in 80 Plates, which began airing in May on Bravo.

A group of young chefs is almost literally parachuted into different cities every week with the task of getting to know the native culinary tradition and mastering it enough to pull off a dinner for locals. Since it’s a reality show, chefs first have to complete assignments to get an “extraordinary ingredient” that is supposed to give them an advantage on their rivals: the possibility of using potatoes to cook pub food in London, the help of an Arab-speaking guide when shopping in the Marrakesh souk, or just time to make labor-intensive tortellini. The completion of the tasks usually includes rushing through markets at a neck-breaking pace looking for stuff, lots of breathlessness, and healthy amounts of catty one-liners.

Revealing the recent lack of originality in reality TV, the show combines two popular food TV genres: the travelogue and the chef competition. The first category features hits like Anthony Bourdain’s No Reservations and Andrew Zimmern’s Bizarre Food, where a host (often male) explores the culinary marvels of an unfamiliar place, displaying either his expertise or his fearlessness in trying stuff that most viewers would find unpalatable.

The genre has expanded to include less exotic fare like Guy Fieri’s Diners, Drive-ins and Dives, where the object of interest is the comfort that can be found in what some could consider the low end of the American culinary spectrum, and Man v. Food, where Adam Richman participates in eating challenges all over the U.S.A.

The other genre, the chef competition, exploded with the Japanese extravaganza of Iron Chefs, and developed into Top Chef, Master Chef, Gordon Ramsay’s Hell’s Kitchen and the short-lived Chopping Block with Marco Pierre White, among many others. By straddling the two genres, Around The World in 80 Plates manages to achieve an acceptable modicum of entertainment value, as viewers get to vicariously explore far-away places while enjoying the drama of the rivalry among the contestants.

The show offers great examples of what can be called “culinary tourism,” which in the words of folklorist Lucy Long refers to “intentional, exploratory participation in the foodways of an other.” Viewers are offered digestible portions of cosmopolitanism and culinary knowledge, two essential components for any self-respecting food lover (or “foodie,” a word that, just like “hipster,” appears to offend those it is used to define).

However, as chefs frantically devour their way through exotic locales, they involuntarily embody subtle colonial attitudes: the culinary treasures of the place they are exploring are there for the grubbing and for the enjoyment of the viewers. The fact that the contestants include individuals of different ethnic background feels like a conscious attempt to dampen any accusation of Eurocentrism. A contestant whose skills and training focused on Thai cuisine was soon eliminated as the other chefs felt that her expertise was too limited, as having a French- or Western-based culinary skills is a surefire recipe for success when trying to cook Moroccan food…

As a matter of fact, the show works on the assumption that professional experience in American restaurants gives the participants enough competence to quickly absorb knowledge about strange ingredients and unknown cooking techniques. At times the chefs come across as arrogant, like when the “secret ingredient” is an elderly lady who can teach them how to make the Tuscan soup ribollita; when they realize that she does not speak English, they do not even ask her to make the soup to learn from her actions.

The way the chefs are evaluated is also dubious. The “locals” that the show trumpets as the real judges of the chefs’ work are often food critics, well-known restaurateurs and their patrons. And the authenticity they seem to embrace comes across at times as vaguely elitist, like in the London episode that presents gastropubs, a relatively recent addition to the local scene, as British authentic cuisine.

The most questionable message that transpires from the show that it is enough to get acquainted with a few ingredients and to cook a few recipes to boast command over a culinary tradition. I am sure many chefs would have their doubts about this approach. But it is exhilarating to assume that a few mouthfuls can make you a culinary expert, and that’s the fantasy the show is selling.

Comments are closed.