A combination of a campfire-toasted marshmallow, chocolate, and Graham crackers, the s’more tastes like scary stories, sticky fingers, and summer vacation. But it should come as no surprise that this summertime standard isn’t exactly a light dessert. One s’more is around 200 calories—but it packs up to 20 grams of sugar. That’s the equivalent of eating nearly five teaspoons of raw sugar.

What is surprising, though, is this: all the ingredients that go into a s’more were once considered health foods—and some have even been sold as medicines relatively recently.

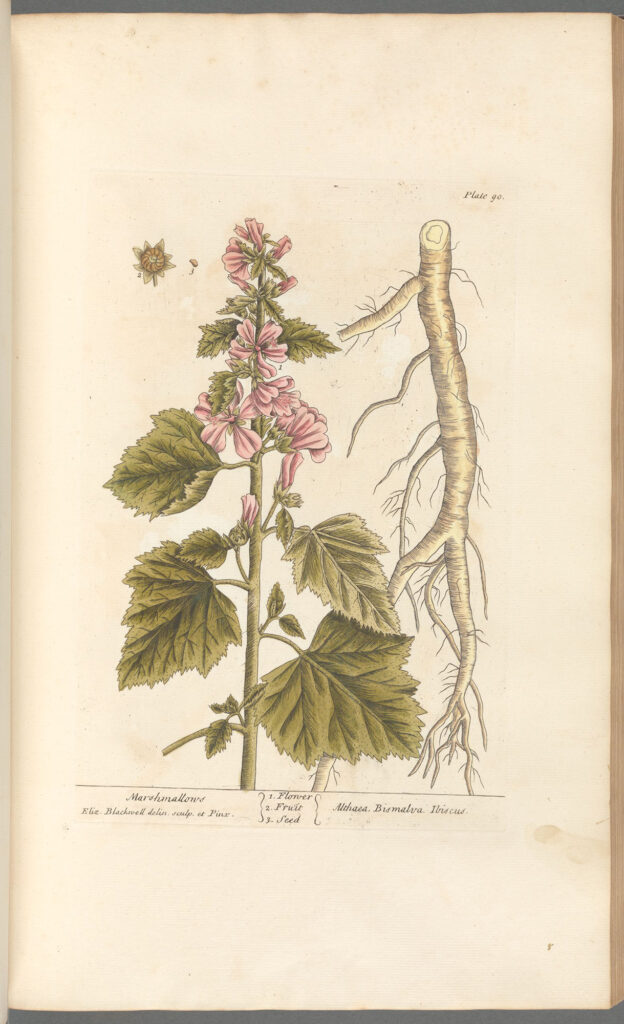

Marsh-mallow

It is hard to imagine a processed puff of sweetness having roots throughout history, and roots in the earth.

The marsh-mallow plant, Althaea officinalis, is native to Europe, Asia, and Africa, but has been introduced widely, including in the United States and Canada. Fresh leaves are edible and were prized, among others, by the Ancient Romans—who cooked its leaves with garum (a fermented fish sauce), but its roots were also a famine food.

Throughout much of history, it was arguably better known as a medicine, typically a cough suppressant.

The plant, specifically its root, comes recommended by some of the earliest, best-known sources in Western medicine. Hippocrates recommended mallow in his work On Ulcers, written around 400 BCE. Dioscorides discussed the medicinal plant in his famous Materia Medica (written in the first century BCE), and just a few years later, Pliny the Elder expounded on it at length in book 20 of his Natural History. He reported several uses, some quite similar to benefits often described today “[mallow] leaves dried and boiled down in milk cure very quickly the most racking cough” but others were more unexpected (“a leaf placed on a scorpion paralyzes it”). Perhaps the most wonderful: a claim that whoever swallows half a cyathus (approximately ~1.5 tablespoons) of the [root] juice daily will be immune to all diseases.

Once you sort through the hyperbolic reports that Pliny passes on, you get more bits of truth: “It is remarkable that water to which this root has been added thickens in the open air and congeals.” The mucilaginous properties of marshmallow root—it basically turns to an oozy mucus upon contact with water—would eventually lead to its culinary star turn.

Marsh-mallow’s reputation as a healing plant was echoed for centuries.

It is mentioned in herbals and other lavishly illustrated natural history books from the 17th century, and herbals and gardening books in the 18th. By the 19th-century in the US, the plant was still in demand enough for druggists and pharmacists to advertise it alongside morphine and cocaine. Marsh-mallow even appeared in the first iteration of the venerable Merck Manual, Merck’s 1899 Manual of Materia Medica.

The marsh-mallow’s oozy goodness eventually caught the eyes of chefs, who discovered that its mucus had a tendency to “fluff up” when aerated—somewhat similar to egg white turning into meringue. As the plant’s healing reputation began to fade with the birth of pharmacology, it became popular as a confection—going from a cough medicine to a treat sold at drugstores and soda fountains in relatively short order.

It didn’t take long for the candy’s name to become misleading. Just as root beer is no longer made from the sassafras root, confectioners quickly found cheaper, and better-tasting ingredients (the actual plant root had something of an acquired taste). Over time, the primary ingredient in marshmallows changed, first from mallow root, then gum Arabic, and followed not long after, and to this day, by gelatin. Along the way, a host of innovations occurred—from the development of marshmallow molds to contemporary marshmallow extrusion technology.

Marshmallows today do not contain any part of a marsh-mallow plant. Though some people still make them the old-fashioned way, it’s a lot cheaper and (less slimy) to use sugar, gelatin, and cornstarch.

Chocolate

Long before the invention of the chocolate bar, chocolate was a medicine, a sometime-currency, a status symbol, and a sacred substance.

Its source plant would likely go unrecognized by many who enjoy it. The large, orange, ovular pods of the Theobroma cacao tree contain the bean-like cacao seeds that, when fermented and dried, can be processed into a constellation of products, including chocolate, cocoa powder, cocoa butter, and more.

Cacao is native to South America’s Amazon basin and was introduced to Central America by ancient civilizations It has been cultivated in these regions for millennia: traces of theobromine, a chemical compound found in cocoa, have been found in artifacts in a site in Ecuador dating back 5,300 years. References to cacao are common in the art and writing of the later Olmecs, Mayans and Aztecs.

For several thousand years running—cocoa, the main ingredient in chocolate—was used in a spicy, invigorating drink known as Chikolatl. This original “hot chocolate” was spicy and frothy.

In the 16th century, the plant’s importance, and especially its perceived value, didn’t go unnoticed by the invading Spanish. They established the Encomienda system in the regions they seized, forcing Indigenous populations to offer tribute in the form of cacao beans. Cacao (and by extension, chocolate) eventually became a luxury good, first in Spain and then across Europe, produced by the oppressed and enjoyed by their wealthy oppressors. In this respect, things haven’t changed. Cacao is now produced mainly in Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire, impoverished countries that consume very little of the end products. Multinational corporations, meanwhile, make billions each year. The actual cacao production process, too, is grueling: it involves machetes, toxic herbicides, hot days, and heavy loads. And the workers? At best, they are in penury; at worst, they are enslaved. Many are children, often migrants fleeing instability elsewhere in the region.

From Cacao to Milk Chocolate

The allure of cacao, and by extension, chocolate, in Europe was medicinal as much as culinary, and the unfamiliar plant was often described in hyperbolic medical terms. In Chocolate: or, An Indian Drinke, published in 1652, Antonio Colmenero de Ledesma (translator: James Wadsworth), claimed it cured the “Plague of the Guts,” what we’d now call dysentery.

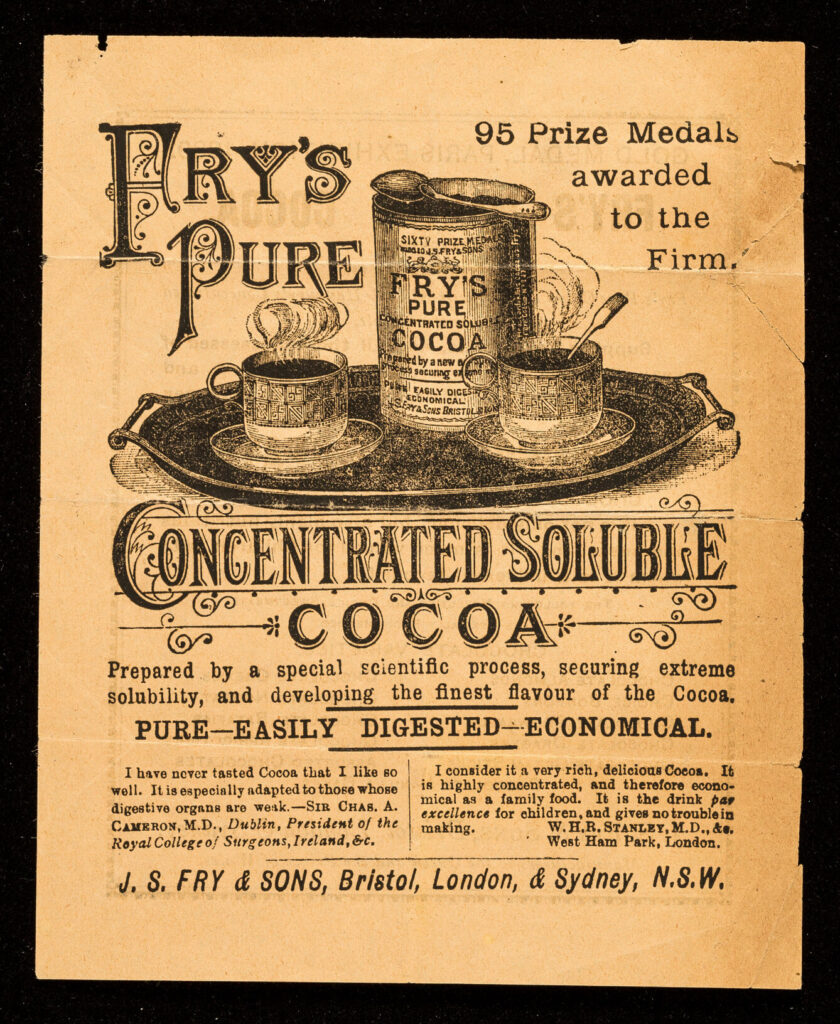

In Europe, chocolate wasn’t immediately a hit with the masses, however. Almost exclusively served as a drink, it was usually enjoyed by the well-to-do, at least until the mid-19th century. Cocoa, served warm with milk and sweetened, became a mainstay of the Royal Navy. Thousands of pounds of chocolate were even issued to the ill-fated Erebus and Terror of John Franklin’s Lost Expedition.

While chocolate was ever-popular in hot chocolate, and used as an ingredient in Victorian desserts, such as puddings and tarts, it really came into its own until it was readily available in a solid form. That didn’t happen until the invention of the cocoa press in 1828, which made producing cocoa powder much simpler. The familiar candy bar followed soon thereafter; it was first produced in 1847.

The arrival of chocolate’s sweet, solid form coincided with upward social mobility in Europe by the middle of the 19th century, and it became what one scholar called a “small luxury” for the working class.

Chocolate pervades culture today, especially in the U.S., which is home to some of the best chocolatiers on the planet, major chocolate manufacturers like Hershey’s and Mars, and chocolate and cocoa in about every form imaginable. And in certain quarters, chocolate—especially dark chocolate—is once again being hawked as a health food. (Never mind that heavy metal contamination in dark chocolate is a real—and recent concern.)

Perhaps in part because consumers (and manufacturers) want chocolate to be good for us, chocolate has been studied in more than a little detail as a medicinal and dietary compound. In Clinical Nutrition, the journal of the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism, a 2018 umbrella review analyzed 240 articles studying chocolate’s effects on health outcomes. The article’s conclusion was no reason to rush to the supermarket: “There is weak evidence to suggest that chocolate consumption may be associated with favorable health outcomes.”

Still, the idea of chocolate as health food is unlikely to go away. It may not improve anyone’s health, but it does help someone’s bottom line.

Graham Cracker

Of the s’more’s three parts, the Graham cracker is by far the youngest component, and maybe the one with the strangest story.

Graham crackers bear the surname of Sylvester Graham. Born in Connecticut in 1794, Graham was a minister—like his father, who died when Graham was just two—as well as a doctor. He bounced between homes as a child, and at one time spent time doing chores in a tavern. It was there, seeing the results of booze consumption, that his worldview crystallized.

Graham became one of the rare advocates for both a meatless diet and temperance in the pre-Civil War US. Through a series of well-publicized lectures, which were soon widely distributed in print, Graham became relatively well known and developed a devoted following that verged on cult-like. His message is pretty familiar today; he was what we’d call an advocate of clean eating. He posited that pure, unadulterated foods were, by definition, healthier, and could even prevent disease. On the other hand, diets rife with meat, alcohol, coffee, or “adulterated” foods could lead to physical, moral, and even sociocultural decay.

Despite his radical 19th-century health influencing, Graham is best known for his thoughts on sex. Graham warned young men about the dangers of male masturbation, which, he cautioned, “rendered this life a pilgrimage of pain” and had inevitable digestive, cardiovascular, hepatic, and mental consequences. But intriguingly, Graham’s views of sexuality and food overlap. In both cases, he was fixated on purity and the absence of stimulation.

Graham had especially strong takes on bread and flour. He taught that God himself specified which foods were best-suited for each lifeform, and that bread, if prepared as intended, was among the best for humans. But in Graham’s era, bakeries were baking on a far larger scale than before—and to do so most economically, they employed the chemistry of the time to cut corners, producing, according to Graham, “light and white bread out of extremely poor flour” made edible because “they have also been able to disguise their adulterations.” For Graham, bread was best when it was as unprocessed as possible and made from coarsely ground wheat.

The earliest Graham bread (or biscuits) were intended to be both as bland and as nutritious as possible. An early recipe is about as basic as you can get: coarsely ground whole-meal wheat flour, milk-warm water, a bit of salt, molasses, baking soda, and yeast. Today, his name is forever appended to a stimulating, sugary snack he would likely have hated. And those Graham crackers? Almost invariably ultra-processed, and made of highly altered and augmented flour. Precisely what Graham feared most.

Graham died relatively young, at 57. The Grand River Times, a Michigan newspaper, didn’t miss an opportunity for one last dig “that vegetable diet, in his case, does not appear to have been peculiarly beneficial.” Still, Graham’s influence persists. Many of the things we consider healthy—whole grains, fresh air, an occasional cold shower or bath—have some connection to Graham. And while Graham’s connection to crackers is orders of magnitude more familiar than the man, his influence didn’t die with him. Some of his proteges are now household names, including the progenitors of the Kellogg and Post cereal brands. And of course, this sex-hating, Presbyterian vegetarian invented the vehicle for the chief delicacy of summer.

History, like life, is weird. You might as well have another s’more.

Brett Ortler is a naturalist, an author, and an editor. His work appears widely, including in Slate, Salon, Fatherly, and many other outlets. He lives in Minnesota. For more, visit www.brettortler.com

Comments are closed.