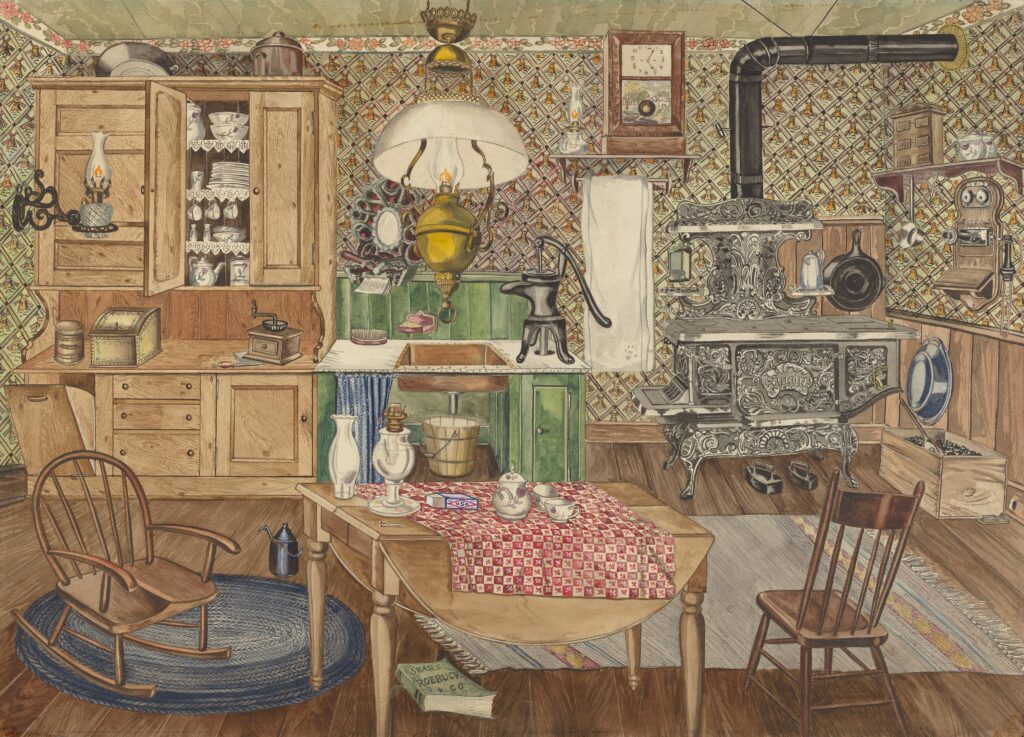

The galley, the work triangle, double ovens, islands, open plans. It was the advent of the Franklin stove in 1740 that created the room we think of now as the kitchen, internal to the family home; kitchen layouts and features have changed with advancements in technology, the economy and class, family makeup. What used to be relegated to the outdoors or the back of the house, smoky and invisible to daily life, is now fodder for glossy magazines. Entire shows on cable dedicated to redecorating, remodeling, and renovating. The kitchen is the selling feature.

Though who does the work of cooking and cleaning in that kitchen has mostly remained the same.

I got the mother I’d always wanted when I was thirteen. The man who’s been my dad since I was four years old married a woman who welcomed me fully into her life. Before the wedding we looked through magazines and laughed about poufy princess dresses and supersized bouquets; she let me help pick out fabric for the bridesmaids dresses and set up the table with the guest book and a fancy, feathered pen. After the wedding, I became her assistant cook as well as dance partner in the kitchen. It was usually just the two of us in the kitchen— planning meals, trying out recipes, laughing at our Julia Child impressions and the songs we made up about cooking. She taught me the basics: how to press garlic, chop onions without crying; how to knead dough and separate an egg; the proper way to melt chocolate so it doesn’t burn. Things she had to learn herself when she was thirteen and took on the responsibility of cooking for her family after her mother got sick. I pictured her at my age, still needing a chair to reach the cabinet over the fridge, as she described the many ways that she had molded Jell-O in those early years of cooking. “I thought I was so fancy,” she said.

Macaroni and cheese was one of the first dishes she taught me to make. It was important to know the right way to make it from scratch, she said — she was called out for serving boxed mac and cheese once, at a dinner party. Boxed was the only kind she’d known growing up, she said, but now she knew better. Macaroni and cheese had to be baked — and the only thing that should come out of a box were the noodles themselves. “We’re worth it,” she said. “Even if we’re just cooking for ourselves.” She showed me how to grate large quantities of cheese — always at least two kinds — in the food processor. Then she talked me through making the roux, explained the importance of keeping the whisk in constant motion. “Tiny circles with your wrist,” she said. She stood near in case I needed help, but let me try on my own, because “that’s how you learn.”

The kitchen at my parents’ old house was a lopsided rectangle. It had three entrances, only one of which had a door that could be closed. It was also the only way to get to the basement or the backyard. A bit of a thoroughfare. The walls were a cheery yellow and the floor a less happy shade of mustard linoleum. Thick layers of white paint coated the cupboards, sometimes making them difficult to open and close all the way. The stove was new and nice — double ovens and a griddle in the center of the burners — but the dishwasher was so ancient it wasn’t even connected to the water. Instead it was on wheels. When you were ready to run a load of dishes, you had to steer the heavy contraption to the sink and connect the tubes to the faucet. Then, there was no using water in the kitchen until the dishes were done. In the meantime, we used the top of the dishwasher like a counter or cutting board, sometimes moving with it toward the sink while still chopping an onion or measuring out flour.

Every December, my adopted mom explains the steps and the science to me as we make latkes without any sort of recipe. Most of the cooking she learned from her parents isn’t written down. It’s in her body — she just knows it — and that’s how she passes it on. We wash and peel and grate and she tells me how letting the potato sit in its own juices creates the starch that holds the latkes together later, when we put them on the griddle. She scoops her fingers into the bowl and dredges up the sticky goop to show me. “It creates what it needs to make it work.”

Waste is something she cannot stand, whether it be potato water found in the bottom of the roasting pan, or guys in my life who aren’t worth it. “Why waste the tears?” she says, as she puts large pieces of onion into the small food processor instead of chopping them by hand. She means the onions, and the guys. “Why waste your time on someone who makes you cry?” But she has a way to say it that doesn’t make me feel like I’m being judged. I listen. And realize she’s right. “I see you with someone more fun,” she says. I tell her I do, too.

Eventually there were cocktails, too. Sometime toward the end of my undergrad years, once I’d realized that drinking cheap mystery concoctions out of plastic cups wasn’t the only way to feel like an adult.

It started with a simple silver shaker and a shot glass. She laid the bartending book open on the counter and talked me through the steps of making the cosmopolitan I knew from Sex and the City. “It tastes better when you make it yourself,” she said. Citrus vodka from the freezer, ice in the shaker, and the martini glasses with a slight blue tint and tiny circles etched up the sides. I was conservative with the vodka and let the lime juice and orange liqueur spill a little over the lip. The cranberry juice was light enough to keep the liquid pink out of the shaker and create a lilac shade in the glass. “Perfect,” she said when she tasted hers, even though she added a splash of vodka after that first sip.

Mixing cocktails was all about finding the right combination. She let me explore with the liquor cabinet and that shaker. “You have to play around a bit to find what you like,” she said. So I did. I poured and shook and sipped. I perfected the Brandy Alexander, which my parents enjoyed, and came up with a few concoctions of my own that were too sweet for anyone but me. Dessert in a glass. She said I could always make a drink just for me.

No one else in my family had my extreme sweet tooth, so she taught me to bake a more mundane variety of desserts: cheesecakes and pies, vanilla cake and butter-cream frosting. Always from scratch. Key lime pie for her birthday, because she wasn’t into cake. Something with pecans for my dad, who was more about the main course than dessert. I saw the real difference once my little brother was old enough to appreciate a birthday cake all his own. He had a thing for sweets, like me, though his tastes were lighter. Strawberry cake with vanilla frosting. He challenged me to be creative with cake ideas. Real berries, layers, checkerboard cake that turned into squares when you cut it open. He whistled as I slid a slice onto a plate for him. “I thought I stumped you this time for sure,” he said. But I always got it right.

Looking for a house of my own now, I think a lot about the kitchen. The layout. The light. The room for potential. I don’t want an open plan, despite what’s in the magazines and on display everywhere I look. I want a kitchen with walls. Something a bit isolated. Small is okay. Old is fine. Needing some work is something I can work with. But I don’t want a view into the rest of the house. I want a kitchen where I can make a mess. Where I can turn up the music and have fun. Where I can forget the television and the rest of the world exists. I want a kitchen that isn’t trying to be something else.

The kitchen has been the domain of women at least since there’s been a name for the room where all the work gets done. Women’s tasks and women’s space. Even as it changes, so much remains the same. I was taught not to confine myself to what the world wanted or expected of me as a girl and then as a woman. I was taught to be loud and direct and say what was on my mind. I was taught that I could — and should — dream wild and big, without worrying about limits. But those lessons all came in the kitchen.

It was always just the two of us working in the kitchen — the mother I’d always wanted and me. I didn’t feel trapped in there; I felt free. All that time to talk and laugh and sing, no one telling us to be quiet. The time to just be. I learned that I am worthy of good food, so I cook it for myself. And I learned that I don’t have to cook for anybody but me. The kitchen is mine to do with as I please.

Emma Burcart lives in Raleigh, North Carolina, where she teaches first grade. She holds an MFA in creative writing from Antioch University Los Angeles. Her work has been published in Cream City Review, The Normal School, and Catapult Magazine, among others.

Comments are closed.