Growing up, I fantasized about dinner consisting of Chinese takeout eaten straight out of the takeout boxes—just like I saw on TV (specifically, I had my dreams of very Gilmore Girls-esque meals where my family and I would order a week’s worth of Chinese takeout, eat it out of the containers, and live off it for a week).

However, I grew up vegetarian in a small town in Alabama, and there weren’t a lot of vegetarian Chinese takeout options—clearly an obstacle to my master plan. As a kid, I felt like I was missing out on a quintessential dining experience (we would eat Indo-Chinese food when we went to the city, and I absolutely loved it—if you’ve never had it, this is my plug for it). When I got older, I moved to bigger cities and my culinary world seemed to expand. Vegetarianism grew in popularity, and I started trying meat; I could finally live out my Chinese takeout dreams and it met every expectation and hope I had for it.

Photo: Stephanie Drenka.

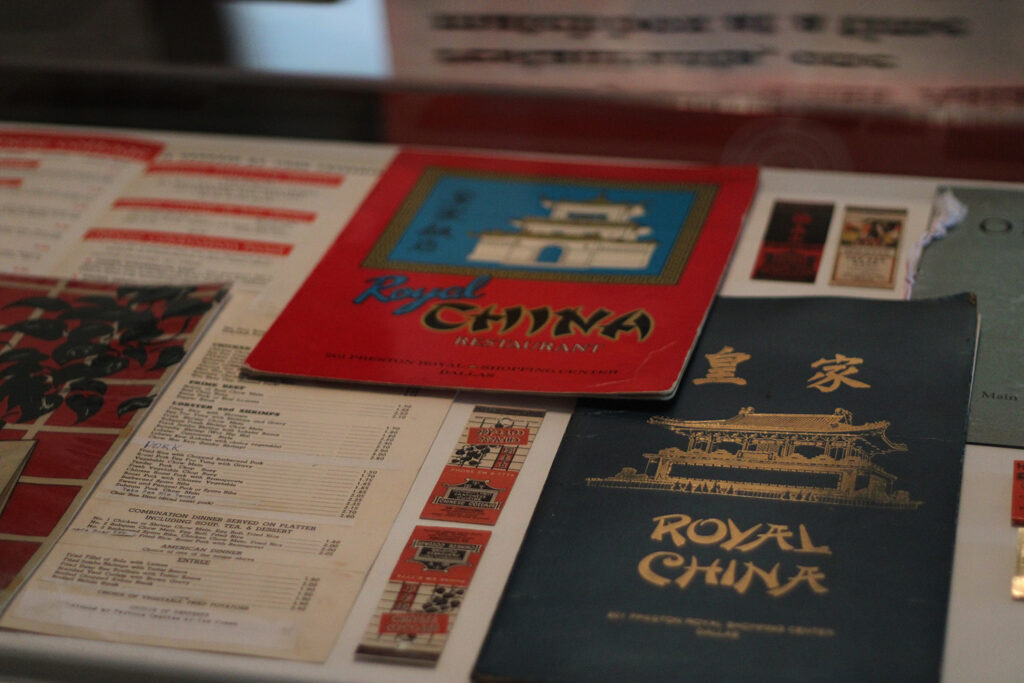

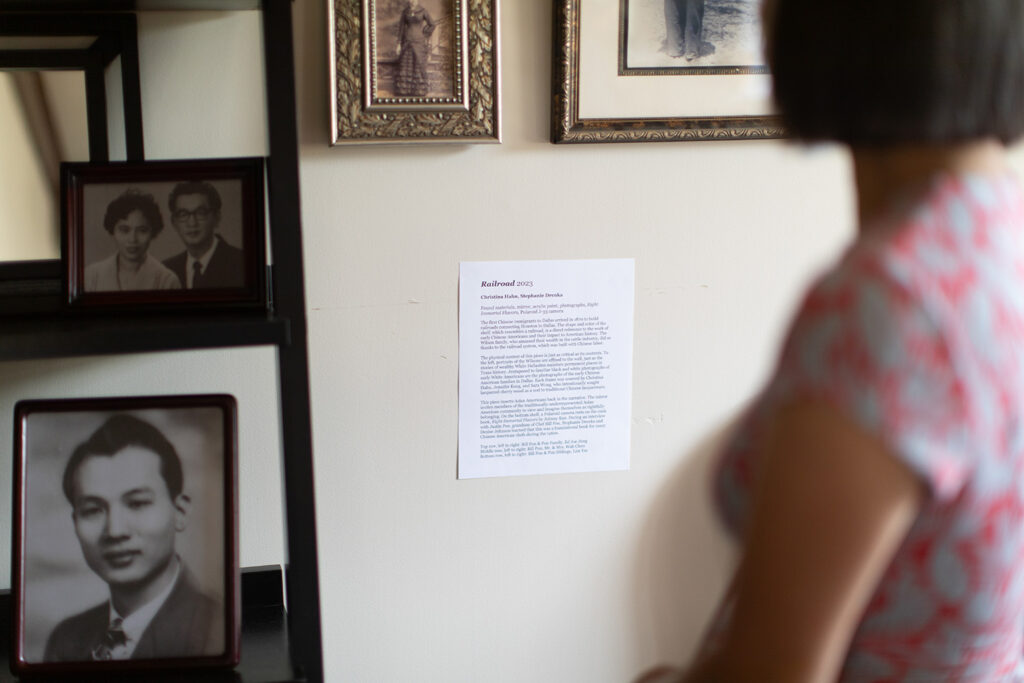

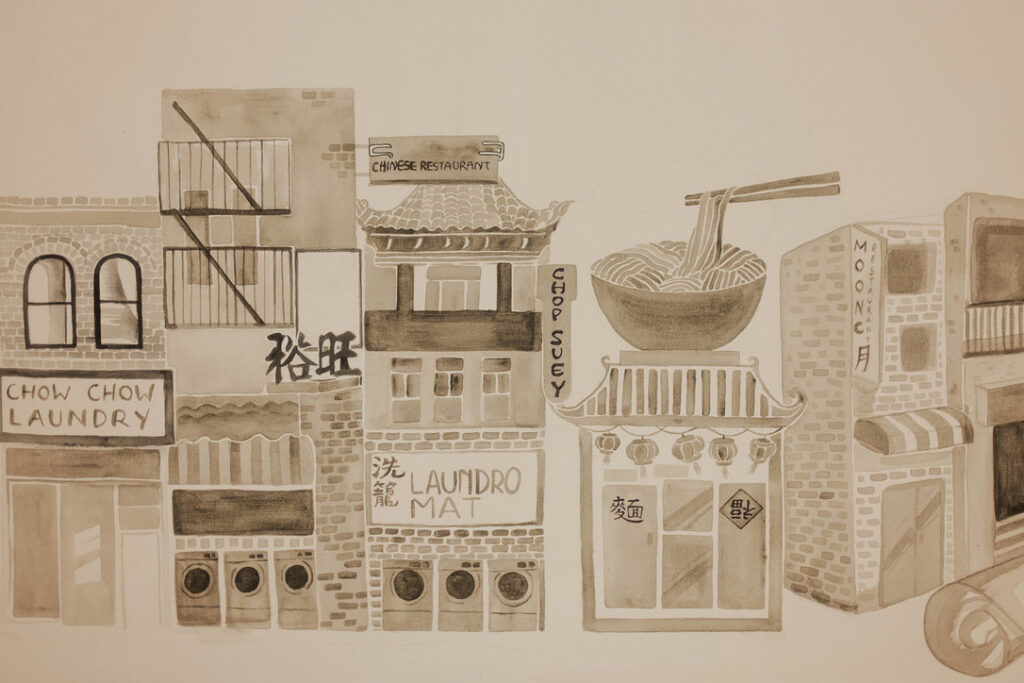

What I didn’t know was the rich history behind Chinese takeout and cuisine. However, Leftover: The Enduring Legacy of Chinese Cuisine in Dallas, a recent exhibition showcasing the city’s Chinese food culture, demanded my attention and my interest was piqued. The exhibit itself was thoughtfully coordinated by creative director Christina Hahn: it featured old menus from the historic Dallas Chinese restaurants (what I would do to pay $1-3 for an entire meal); replicas of restaurants; photos and videos from decades past highlighting the various restaurants and people who created them; and art installations created by high school students from the DFW area, including a mobile constructed of paper fortune cookies. The talent and depth that came through the student pieces was especially striking. It all told a complex but meaningful story as you walked through the rooms–imagining what this time in Dallas looked like through the lens of the Chinese American community in Dallas. Stephanie Drenka (who I had the opportunity to meet and let me just say that she is who I want to be when I grow up) and Denise Johnson started the Asian American Historical Society in Dallas to preserve the amazing history of the Asian American community in Dallas, and this was one of their first public exhibits.

You can feel the effort and pride in the Chinese restaurateur community throughout the exhibit. I came to learn that the history of this community was one that required fight. Around 1872, the first Chinese immigrants arrived in Dallas after working on the railroads. Ten years later, the Chinese Exclusion Act was signed. By then, hate sentiment toward the Chinese community had already set in. Chinese Americans couldn’t get jobs outside the community, and many turned to starting their own businesses and supporting each other. Eventually, many established restaurants as a way to provide their cultural food for the community. As restaurateurs struggled to access ingredients, as many ingredients had to be brought in from San Francisco, the Chinese culinary scene in North Texas continued to innovate; entrepreneur Buck Jung supplied wonton wrappers, fortune cookies, and noodles to the the Dallas Chinese community, and ultimately became a major supplier for the eastern United States, allowing for a more expansive map of Chinese cuisine. This was all a direct reflection of the community’s constant resilience in Dallas.

That’s what showed in the exhibit and the work Drenka and Johnson are doing—resilience. The Dallas Asian American Historical Society hosted a private showing for the families of the restaurateurs who were such an essential part of this history, and according to Drenka, the sense of community that was in the room during the event was palpable. Even during my visit, family members were walking through the exhibit and you could feel the emanating pride.

What to me was a dream based on TV and movies is so much more. It is a community that is resilient, that fought, that innovated—in the face of hatred. It is a community that has left its mark not just on Dallas but on the entire country. It goes beyond the food: it is a rich history that deserves to be highlighted and preserved.

I could sit here and tell you of all the stories, of all the people whose histories make up this exhibit, but that would do a disservice to the curation of art and artifacts at Preservation Dallas’ Wilson House, where these families and community members are telling their own story. Rather, I implore you to read the stories for yourself which are being highlighted by the amazing team at the Asian American Historical Society; or, for those in the DFW area, go to the exhibit before September 22 and feel the magic yourself.

The exhibit program rightfully says on the back: “The legacy is here” and I couldn’t agree more.

“Leftover: The Enduring Legacy of Chinese Cuisine in Dallas” will remain on view at the Wilson House, located at 2922 Swiss Ave, through its closing event on the evening of Friday, September 22nd. For further information, please visit the exhibition page.

Shivani Patel is an attorney by day, baker and lover of all things food by night. She graduated from the University of Georgia with BAs in Linguistics and Public Relations and a JD. She currently lives in Dallas, Texas with her soon-to-be husband, and with this piece, she is fulfilling her dream of being a food writer.

Comments are closed.