“The sun set in the sea; the same odd sun

rose from the sea,

and there was one of it and one of me.”

A long-since rescued Robinson Crusoe speaks these lines—recounting the rituals of his island, after his shipwreck—not in Dafoe’s novel, but in an Elizabeth Bishop poem called, “Crusoe in England.”

In the poem, a world-weary Crusoe finds himself on the other side of his adventures, living in relative comfort and boredom (bordering despondency) on “another island/that doesn’t seem like one.” There, the local museum has asked him to donate the scarce remaining items from his time as a castaway—humble effects, once critical to his survival: “goatskin trousers,” “shriveled shoes” and a knife that “reeked of meaning like a crucifix.” Though he certainly understands that his life and his experiences are a natural source of vicarious excitement and fascination for museum-goers, this survivor unmoored once again by the fact of his survival, cannot help but wonder: “how can anyone want such things?”

This question—which seems at once, to indict the voyeurism that accompanies calamity and to diminish the significance of the heroic and extraordinary details of the personal life, caged in its relics—is at the heart of much of Bishop’s work and process.

Her own life was shaped by frequent disaster; yet, it is rare to find anything akin to autobiography in Bishop’s poems. Her father died when she was only an infant, her mother was permanently committed to an asylum by the time she was five, parentless, she spent the remainder of her childhood (and seemingly her entire life) displaced from any coherent notion of home. However, these grim details never explicitly surface in her poems—it is as though she must have always been asking of the impulse to write about her many sources of anguish: “how can anyone want such things?”

Rather, she devoted her poetic imagination to the deceivingly ordinary and impersonal things of this world—questions about travel, a caught fish, an almanac—deriving from them the profundity of insight and meaning that readers often turn to the lived experiences of memoir and biography to find. For all their characteristic detachment, her poems never register as journalistically or anthropologically removed; alternatively, even her most minor poems seem—by an alchemy belonging only to her—to be infused with vital warmth and uncanny familiarity.

For instance, she gives us Crusoe—a fictional character, infamously mistaken for true, and exported from another writer’s novel—that lives, first in the wreckage of his ship, alone and always dreaming of other islands; then, in the wreckage of his own survival, with only a small handful of items that seem to confirm, with their presence, the totality of all that he has lost; Crusoe, who comments on his own circumstance, saying:

“I often gave way to self-pity.

“Do I deserve this? I suppose I must.

I wouldn’t be here otherwise. Was there

a moment when I actually chose this?

I don’t remember, but there could have been.”

What’s wrong about self-pity, anyway?

With my legs dangling down familiarly

over a crater’s edge, I told myself

“Pity should begin at home.” So the more

pity I felt, the more I felt at home.”

***

By the time I came to my life, my family’s traditions, talismans and rituals had all been thoroughly established. When I was younger, I mistakenly and naïvely assumed that this was true for most people. However, a few years ago, I was having a conversation with a friend who explained that he feels he has inherited nothing—no grandfather’s pocket watch, no religion, no increasingly foreign language, no rites of passage that extend beyond the succession of his surname—and that he is, therefore, always on the lookout for things that he could, one day, “pass down.” I couldn’t help but feel somewhat envious.

My father was a deacon at our local parish. He baptized both my brother and I and administered my first holy communion. While it is common for many families to say grace before meals, prayer in our house was far from typical: we had homemade booklets (not unlike chapbooks) replete with prayers and songs to be read and sung on each and every night of Advent, Wigilia and Christmas; with holy water and incense he blessed our home as my brother and I would compose the initials of the three Magi above our doorframes during Koleda, the feast of the epiphany; and during holy week, pysanky were gingerly painted, lambs were sculpted out of cake and butter, and we spent consecutive days in church—helping him, behind the scenes— that would ultimately culminate in the epic Easter vigil, a uniquely long mass that would begin with my father singing “The Exsultet” to the hordes of gathered faithful from his wheelchair.

Needless to say, the rituals of Catholicism—and more particularly, the many specific ways in which they are intermingled with my father’s Polish heritage and my mother’s Irish heritage—loom large in my memory and imagination. However, we did have secular traditions, too; and many of these involved food.

***

My parents traveled quite a lot in my infancy. Together, they owned a company called Whole Person Tours—a travel agency that specifically served Americans with disabilities and uninhibited ambitions to travel abroad. Though already remarkable in its aim, their decision to provide this service in the 80’s—even before the Americans with Disabilities Act had been signed—is even more so. I love imagining the things that they saw together and allowed others to see. I suspect they had many an incredible meal. Yet, for all of their more exotic adventures, their own honeymoon was spent more humbly in Colonial Williamsburg. It was there that they would come to taste, for the first time: King’s Arms Tavern Peanut Soup.

The 1971 edition of The Williamsburg Cookbook, from which my family would reproduce this recipe, says little about the soup’s origins—only that: “Brazil is the native home of the peanut, the ‘ground nut’ that sailed with Portuguese explorers to Africa;” therefore, my assumption is that our soup is likely a variation on a much more traditional West African soup. In this iteration, its only ingredients are: onion, celery, vegetable stock, heavy cream and peanut butter. It requires that the onions be slowly simmered in butter until they are brown; that the ingredients be stirred vigorously or blended together once the peanut butter is added, and that it be served alongside finely diced peanuts and dried slices of bread called, “sippets.” It does not require much effort or time and the result is both extremely decadent and comforting.

Peanut soup was a regular fixture of our annual Thanksgiving dinner. To this day, it is my favorite part of the meal. This past November, for the first time in my life, I endeavored to be the one to make it. And in short, I was afraid.

I wasn’t so much anxious that I’d fail at making the soup or that I’d burn the sippets. As I mentioned before, it’s really quite an easy dish to prepare and my talented wife—a professional cook and baker—would be alongside me to repair any damage I might cause. Rather, I was terrified that what I made would fail to satisfy the myriad implicit demands we make of our relics. Without explicitly being able to explain to myself why, I felt that this soup—if it was going to be made correctly—had to do more than be made accurately. Instead, it would have to nourish and satisfy my nostalgia; it would have to, in its own brief and limited way, transform my kitchen into my parents’; it would have to be able to teleport my senses from Thanksgiving 2019 to Thanksgiving 1987 and to every subsequent celebration in between—it would have to do all of this and so much more, because it has survived.

I am not a Catholic. My father has been dead for 21 years. My brother and I are estranged. Though I am lucky that my mother would be able to taste the soup that evening, and tell me how it came out, every other seat at my table was occupied by a person different from the ones I seat at the table in my memories of this meal. Peanut soup, for better or for worse, is numbered among the flotsam of my life and in my making of it, I knew I had to honor it as such.

However, I could not help but be reminded of Elizabeth Bishop and Robinson Crusoe. I found myself asking why we continue to make demands of things to which we are already indebted for our survival; things that with us, have too survived? On the one hand, I can understand the impulse to keep such things as a means of providing the self and future generations with a sense of heritage. On the other, I can conceive of how the presence of those things that persist in the wake of so much loss, might prompt a person to desire abandoning these emblems of their painful past; to ask, dismissively: “how can anyone want such things?” Yet, in making the soup, I came to consider how ritualistically watching the sun set and rise from the sea must have immured Crusoe in the history and memory of his wreck; but how, in the risen sun’s persistent “odd”-ness—both its strangeness and its solitude— Crusoe also learned to recognize himself and his place in the universe.

For as long as the sun continues to rise and set on Thanksgiving day, I will continue with some degree of self pity to serve peanut soup at my table; and the more pity I feel, the more I will feel at home.

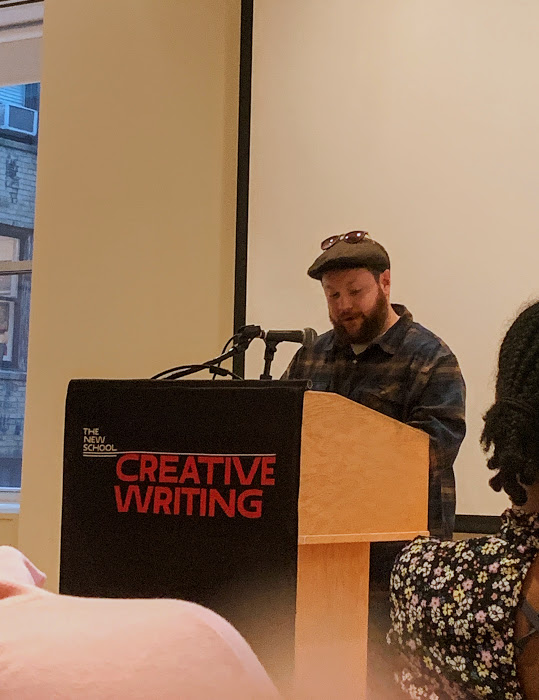

Aleksander Zywicki is a first-year MFA candidate at The New School. He teaches AP English Literature in Bayonne, New Jersey. He lives & writes in Jersey City.

Comments are closed.