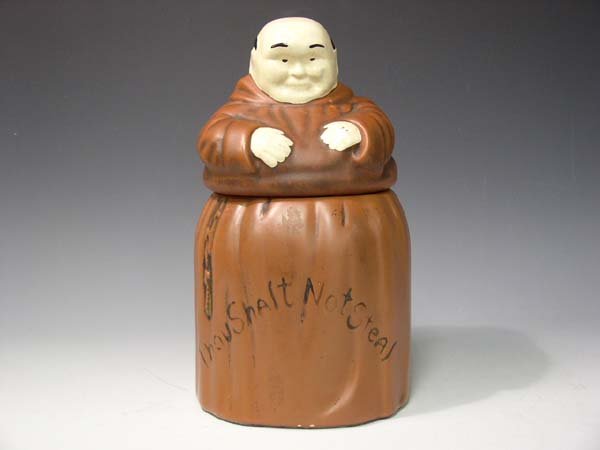

My grandmother made a special stuffing on Thanksgiving: gizzards, stale bread and pearl onions baked to the consistency of pudding. She made it annually in a small kitchen that smelled of cigarettes. A cuckoo clock jutted out from the wall, and each hour the little bird appeared and the chimes rang. My grandmother was stout and loving. The kind of woman who had a cookie jar in the shape of a Franciscan monk, I Shalt Not Steal written across the chalk potbelly. The stuffing was a melting dish, the kind you gulp down, a dish one could be thankful for even after a bad year. Once my brother missed Thanksgiving and my grandmother thought about shipping it to him. I thought of the plastic wrapped Pyrex dish launched on a shipping plane, arriving intact, steaming.

The dish was called Fruit of the Ocean. The fruit was fresh – fish from the sea. It was Italy; the cook was my lover’s uncle, and a grimacing unkind man. He made it for me because those who do not eat meat in his country eat fish. I cannot stomach fish. I chewed the octopus, gnashed it down with my molars, mind suspended in blank animal determination until I was sick with it. Afterwards, I turned yellow as limoncello. That night my lover and I gripped each other in the uncle’s house in a small room with small bed, a small window and outside the large illuminating yellow moon. The happiness of first love, the recognition of your own youth and beauty: it was ours. We were full with it.

My mother would swirl cottage cheese into the Miracle Whip and spread it on white bread. It was delicious with tomatoes: tart and sour and sweet. She made shit on a shingle, wheat toast with chicken gravy and peas. Once she baked a cherry pie, but forgot to pit the cherries, and her omission is at the core of my love. She is not a cook. She is a strong and solitary woman. She was sad after she bore me. She sat in a suburban house in Connecticut with her two young children. The cheap clock ticked loud on the wall. Then it was 5, and she would turn on baseball. Drink two cold cheap beers. I eat like my mother. I am somewhat uninterested in food. At eleven, I eat lunch. I eat plain food and go on with my business.

It was New Years and I was in Texas. My lover was tall, lean, beautiful like a rare bird. His glasses were inch thick, his mouth would slide from downturned rest into the widest, most gleeful smile. I insisted we prepare a large meal for many people. He was obliging. I had recipes; I sent him for ingredients. I was deeply in love but did not know. I was focused on the meal: the guests, the food – something with feta – spanakopita? The Christmas tree was still lit in the living room. Days before we had sat at its base and opened presents like children. This man had a magic, good child in him and two or three beasts. We unfolded the card tables and placed them against a dull wall in the living room. We had no time to clean before the guests arrived; instead, we made our singular love. The kitchen stank of butter. Outside, the desert and cars pulling up. The food was consumed; everyone drank until late, then left. I went to bed in my ignorance. It was the desert at night. It was cold.

The food at my wedding was cheap and we wanted it that way. There were meatballs and sauce; platters of mass produced cheese and meats. There was a lasagna, the edges like hard burnt plastic. The cake was my favorite: a three tier white cake, the bottom two layers were iced cardboard. Only the top was edible, and we ate our cake until it was time to go home. We arrived home, my husband, my best friend, and myself. Jenny and I sat on the fire escape and drank champagne and shared a cigarette. She left; Alex and I fried up two grilled cheeses — sourdough bread, the cheapest cheddar—and opened a few presents. There was laughter and then love and sleep, and it went on.

It was March and snowing. My water had broken as I walked home carrying groceries from the store I hated, that smelled like mildew and dust, old lettuce and boxed Polish desserts. I long for it now – it rests in my memory, odorless. My husband took the G train to Nassau. He raced home. He climbed the four staircases. I was cleaning, I had been cleaning for some time. He put me in the bath, gave me a small glass of red wine and boiled cheap ravioli. He lit candles we’d bought for a hurricane. I ate nothing. I cleaned on my knees in the candlelight. Then we put on a movie. He slept. I did not sleep. I was adrift on a rolling ocean. My husband in sleep is as he is in life: serious, committed to the sleep. Receptive. Enduring. We rode in a cab to the hospital. I saw the dawn, I called my mother. At the hospital I was told to eat nothing. I snuck energy bars between nurses. I drank a terrible orange drink. I waited until the animal labor came. The animal tore me in two and the animal left and I was handed my son. First he couldn’t breathe; then, he could. I was a mother, my self broken into parts. The next day, my son asleep in his plastic bin, we ate food from the drugstore: saltines, a plastic container of pasta salad with canned olives, splashes of green herbs. We sat at the window, our beloved city waking up. We ate silently, regarding the other, terrified and resolute.

Then I was the food. My son drank from me, clung to me like a barnacle on a ship. If I was a ship I did not know it; I did not know what I was. We sat together on the love seat, my husband, my son, and I, a movie playing, my son eating for hours like he would never stop, like our bodies would never be separate. I was brought cold almond milk with a straw, bananas. Our friends brought dish after dish to the apartment, bright visits full of astonishment and love, us blinking our eyes in disorientation. Then the door would shut and we would return to the love seat and resume a film and Sam would eat. His tongue was tied. It was hard for him to eat from me. He did not gain weight. He was nearly 5 pounds. His legs were like insects. He would not stop eating. The milk was watery and white and tasted sweet. He ate. We put on another film. Months passed like this. Then he was made bigger by the milk and one day, after many days, he laughed.

Alison Powell’s first collection, On the Desire to Levitate, won the Hollis Summers Poetry Prize and was published by Ohio University Press in 2014. She has received awards from institutions including the Vermont Studio Center, Millay Colony of the Arts, Fine Arts Work Center of Provincetown, and elsewhere; work has appeared in Boston Review, AGNI, Guernica, Black Warrior Review and elsewhere. She is Assistant Professor of Poetry at Oakland University, and lives in southeast Michigan with her husband and son.These poems are from her second collection in progress, which draws on Millerism, Noah’s Ark, extinction, Christopher Columbus, climate change, and other apocalyptic matters.

Alison Powell’s first collection, On the Desire to Levitate, won the Hollis Summers Poetry Prize and was published by Ohio University Press in 2014. She has received awards from institutions including the Vermont Studio Center, Millay Colony of the Arts, Fine Arts Work Center of Provincetown, and elsewhere; work has appeared in Boston Review, AGNI, Guernica, Black Warrior Review and elsewhere. She is Assistant Professor of Poetry at Oakland University, and lives in southeast Michigan with her husband and son.These poems are from her second collection in progress, which draws on Millerism, Noah’s Ark, extinction, Christopher Columbus, climate change, and other apocalyptic matters.

1 Comment

Memoir, bite by bite.