I have an anxious and highly ambivalent relationship with food. This is informed by a thoroughly demoralizing struggle with digestive disease dating back to early childhood, and in my adult life with an evolving awareness of how political power is derived out of the universal need to eat. I don’t think it’s simplifying things too much to say that food is the terrain of struggle, of our bodies and our lives. So it is with some trepidation that I approach a topic that refracts for me in such a charged and diffuse manner, and with such interrelated complications.

The problem, as it were, begins with the surrender of the power to grow our own food, and the image that crystalizes this for me is that of the cargo cults of the South Pacific forsaking their lineage of independent subsistence in favor of ritualized dependence on some impersonal, heavenly power.

The cargo cult phenomenon emerged among indigenous Melanesian populations during World War II as a result of another phenomenon, that of military supply containers dropping out of the sky to support U.S. troops on the ground. The islanders saw photographic evidence of a bountiful life of leisure in American magazines, witnessed uniformed men laying down airstrips instead of crop fields and invoking cargo-bearing planes with radio transmitters rather than cultivating the land, and translated this into religious iconography:

The basic premise of the cargo cult is that tribal ancestors, the foundation of the islanders’ indigenous religions, are the source of all the material possessions which are now being controlled by the whites. In order to redirect the flow of this cargo back to its rightful recipients, certain rituals must be enacted to mollify the ancestors. These actions have often included ceasing all productive work and destroying crops and pigs to demonstrate sincere belief in the imminent arrival of the cargo. [from Stuart Swezey, “Cargo Cult” introduction, Amok Journal (1995)]

This kind of mystical materialism has obvious parallels with consumerism, but it’s also relevant on a more encompassing scale. I’m thinking specifically of industrial civilization’s occulting process that divests the populace of the knowledge of food production in exchange for subjugation and consumer goods, e.g. instead of gathering water from the sky or ground, or food from the earth, people perform symbolically empty rituals for forty-some-odd hours per week in order to induce water to fall from the faucet and food to spontaneously manifest in grocery aisles.

One could argue this transition away from individual and community ownership of food production is not an incidental result or necessity of societal evolution, but a strategic maneuver that enlarges the range of population control by several orders of magnitude. There’s a quote that’s been attributed to Henry Kissinger that’s probably bullshit but no less true to the world in which we live: “Who controls the food supply controls the people; who controls the energy can control whole continents; who controls money can control the world.”

Let’s set aside energy and money and just focus on food here, going all the way back to the beginning. In its Edenic form, human work is the work of human subsistence, and the technology of our work is water, sunlight, earth, seeds and time. This is the foundational technology of human life and all forms of civilization, and it is this technology that industrial civilization obscures and replaces with the mechanisms of its own survival. What many of us call “work” today is what we do instead of work – a mediating activity that slight-of-handly naturalizes the daily sacrifice of our bodies and time, and allows the intrinsic value of our labor to be siphoned off, at variable speeds and volume, so it can be reallocated in systems that support neither our values nor self-preservation.

Narratives are key to this obscuring or occulting process, whether it’s straight up myths like that of teleological progress and the corresponding superiority of the present over the past, or more embedded lexical maneuvers like the application of the term “laws” to the physical structure of the universe (2nd law of thermodynamics, etc.) as a way of reflecting back and infusing arbitrary human laws with a sense of the natural and immutable.

With regard to the probably fake Kissinger quote above, the second step in controlling the people via food (after erasing personal ownership of its production from cultural messaging) is to drain food of its functional purpose and give it a narrative purpose instead: people eat first of all because it delivers a cultural experience, as evidenced by every single advertisement ever; food as a vehicle of nutrient delivery is a secondary consideration, or value add. This step enables the third step to occur without remorse, which is to drain food of its nutritional value: what is now labeled “food” is often, functionally speaking, garbage or poison. The benefit of this step is twofold: “food” can be produced and distributed more cost-effectively and with greater mechanized efficiency than food (at least within current, petroleum-based world systems), and the compound physiological damage caused by ingestion of “food” products over time systematically converts people into assets that can be squeezed by the health care industry.

I can attest to the efficacy of this strategy first hand. I had my first bowel surgery when I was 18. I’ve had a few more since then. The first was a colectomy in response to repeated hospitalizations for ulcerative colitis, an inflammatory disease of the large intestine. The rest were emergency surgeries for small bowel obstructions caused by an overgrowth of scar tissue from the initial surgery, and then scar tissue from each subsequent surgery, ad infinitum. In between surgeries I developed migraines and fibromyalgia. I received iron infusion therapy and occasional blood transfusions over a period of ten years for severe, chronic anemia. I had a pulmonary embolism at age 33. Presumably, all of this is symptomatic of an underlying autoimmune disorder conditioned by an unfortunate mix of genetic predispositions and environmental inputs. The most significant input? Food, or more precisely, “food.”

At this point (age 37), I try to avoid gluten, dairy, sugar additives, soy, nightshades, genetically modified foods, fluoridated water and anything else that’s been documented or rumored to trigger an inflammatory response in susceptible physiologies, and I eat minimally processed, organically grown food wherever possible. I also follow a fairly aggressive supplement regimen to address the absorption deficiencies of my reconstituted digestive system, and recently underwent an intensive, specialized form of physical therapy designed to soften and loosen the surgical adhesions entangling my insides.

As can be surmised from the above, keeping me alive has been an expensive and labor-intensive process. Like war, chronic illness is a racket.

What happened to me, the consequences of which are still happening, was systemic bodily collapse due in part to a deficiency of real food. The same thing happens to political bodies. There are studies out there that correlate riots and revolts with the price or availability of food, as noted in the following from Scientific American (by way of Chris Martenson’s Peak Prosperity site):

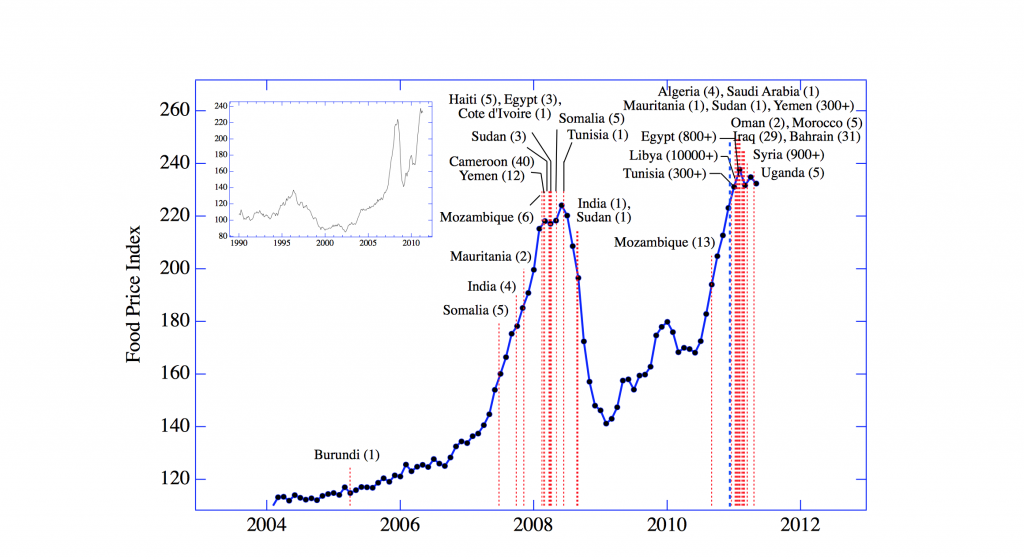

The surging cost of grain throughout the Middle East, along with Tunisian fruit and vegetable vendor Mohammed Bouazizi setting himself on fire on December 17, 2010, are frequently cited as factors contributing to the Arab Spring. Four days prior to Bouazizi’s self immolation, [Dr. Yaneer] Bar-Yam and his NECSI colleagues submitted an analysis that highlighted the risks of rising food prices and anticipated an event like the Arab Spring. Their research included a model built using data from the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization’s Food Price Index, a measure that maps monthly changes in international food costs. The model found the likelihood for rioting increased when the index reached above 210.

On the graph below, the black dots are food prices and the vertical red lines are riots (with death tolls in parentheses); they show the index exceeded 210 during the food crises of both the 2008 and 2011.

For the aspiring Kissingers of the world, the key takeaway is that people will put up with just about anything except starvation. All other degradations, such as oppression, enslavement, and killing their friends, are probably acceptable. This insight already pervades our networks of surveillance and control, as evidenced in this photo from an April 2010 joint exercise by the Anchorage Police and the Alaska Army National Guard, in which sex, booze, hoodies and food are staged in all of their obvious illegality — but it is the unambiguous declaration of hunger in broad daylight (a “FOOD NOW!” sign) that is truly blasphemous and deserving of excessive, armed response:

Those of us with more modest, un-Kissinger aspirations must look elsewhere for models of how to live life on a planet like this. My layperson recommendation is currently permaculture, a life practice grounded in sustainable efficiency and patterned after natural, regenerative systems. Short for “permanent culture” and focused on establishing exactly that, its core tenets are care for the earth, care for the people, and care for the future (or return of surplus, converting profit and waste back into the system). The term was coined in 1976 by Australians Bill Mollison and David Holmgren in their article A Permaculture System for Southern Australian Conditions, and popularized worldwide as an approach to developing sustainable human habitats, with an emphasis on integrated food production. Mollison describes it as “a philosophy of working with, rather than against nature; of protracted and thoughtful observation rather than protracted and thoughtless labor; and of looking at plants and animals in all their functions, rather than treating any area as a single product system.”

Developed in response to the Anthropocene’s history and apparent endgame, permaculture accounts for the big systemic risks we face today, what philosopher Slavoj Žižek calls the four horsemen of the apocalypse: our escalating ecological, technological, economic and socio-political catastrophes. It also addresses what’s implicit in Žižek’s allusion to The Book of Revelation: our collective spiritual crisis. I was exposed to the principles and applications of permaculture this summer at an ecovillage in the temperate rainforests of North Carolina, where I lived off-grid and learned about foraging and forest gardening, rainwater harvesting, dry stack masonry, sheet mulching, humanure and the like. The goal is to minimize energy inputs, foster synergies and produce no waste; waste just means you haven’t optimized your system properly, or as Buckminster Fuller says, “Pollution is nothing but the resources we aren’t harvesting” – a quote affixed to the wall of an outdoor composting toilet at the ecovillage. Handbooks like the Toolbox for Sustainable City Living and in-progress civic projects like The Plant (a former meatpacking facility in Chicago converted into a vertical farm, educational center and food business incubator with on-site energy production) demonstrate the viability of this vision even in urban areas.

I say all this not as an expert (I’m barely an amateur) but as someone who’s had, like most people on this planet, a hard time here. Our globalizing civilization and its cultural narratives are engineered to convince people that acting like self-destructive aliens is our natural mode of being. Our bodies and spirit attest otherwise. Reclamation of the food production cycle, by individuals and local communities, is the most fundamental step we can take toward a rehabilitated present and a future that has a future. Tending and eating from a food garden is at once a political act, a strategy of risk mitigation, and an embodiment of our core functionality. In lieu of something useful like a list of common companion plants for your regional climate, I’ll leave you with a poem:

The human

condition

is what denial

of the human

function

looks like.

The Earth

bends to

the will of the Sun.

Dan Hoy is the author of The Deathbed Editions (Octopus Books, forthcoming 2015), Omegachurch (Solar Luxuriance, 2010), Glory Hole (Mal-O-Mar, 2009) and other collections. He is an ongoing contributor to the multidisciplinary blog Montevidayo, and his personal website is The Pin-Up Stakes.

Dan Hoy is the author of The Deathbed Editions (Octopus Books, forthcoming 2015), Omegachurch (Solar Luxuriance, 2010), Glory Hole (Mal-O-Mar, 2009) and other collections. He is an ongoing contributor to the multidisciplinary blog Montevidayo, and his personal website is The Pin-Up Stakes.

Featured image via Wikimedia Commons.

Comments are closed.