By Fabio Parasecoli, Associate professor and coordinator of food studies, New School – NYC

From the Huffington Post

Rarely, as in recent months, has the European Union been so unpopular among its citizens. In May 2014, the elections for the European Parliament, its legislative body, saw the success of political parties whose admitted goal is to reduce the meddling of the Union in the daily activities of those living across its 28 Member States. In fact, the EU is often perceived as another layer of wasteful, inefficient, and unbending bureaucracy that weighs on the already weak economic recovery of the continent.

Most Europeans have a clear sense of how much the EU regulations have influenced their food system, from safety to trade, from GMO crops to product traceability. Standardization has been a hotly debated issue. The Slow Food movement lobbied very effectively against a blind application of the HACCP (Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points) system, introduced in 1994 to ensure safety in food production. The organization pointed out that not all manufacturers — and especially small, artisanal ones — are well suited to adopt the same criteria as industrial enterprises. On the other hand, Europeans do appreciate interventions in the case of emergencies. The European Food Safety Authority was established as the most appropriate response to guarantee a high level of food safety.

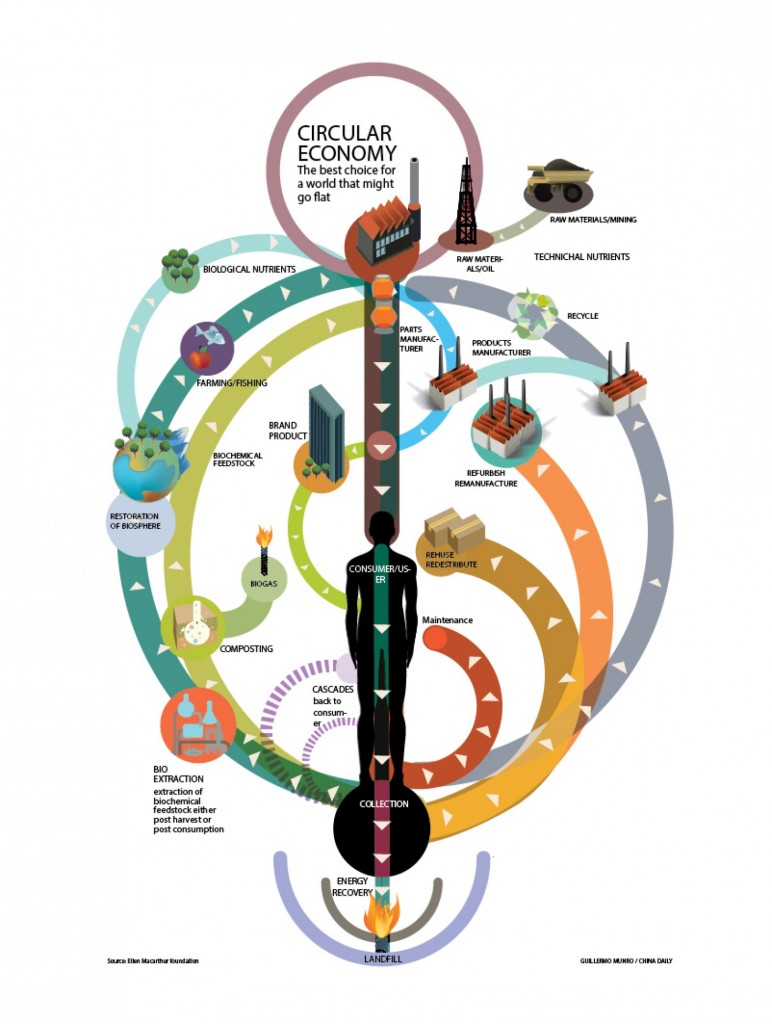

This time, the EU is weighing in on issues of sustainability and waste. On July 2nd, the Commission approved a set of proposals to increase the recycling rate in the Union and facilitate the transition to a “circular economy,” a system where no products go to waste and materials are constantly renewed. In a Q&A memo, the Commission explained: “a circular economy preserves the value added in products for as long as possible and virtually eliminates waste. It retains the resources within the economy when a product has reached the end of its life, so that they remain in productive use and create further value … The circular economy differs from the prevailing linear ‘take-make-consume and dispose’ model, which is based on the assumption that resources are abundant, available and cheap to dispose of.” In this economic model, biological materials should always reenter the biosphere safely, while technological materials should circulate without entering the biosphere at all.

The potential impact of these theories and practices, which systemic design has embraced as its guiding principles, is enormous, including its possible influence on food systems. Some of the Commission’s proposals would have a direct influence on the way food is produced, packaged, distributed, and consumed. By 2030, the Union should reach the goal of recycling 70 percent of municipal waste and 80 per cent of packaging waste (glass, paper, plastic, etc.). From 2025, recyclable and biodegradable waste should not be allowed in landfills, to be eliminated completely within the following five years. A section of the document deals explicitly with food, highlighting record-keeping and traceability as tools to limit hazardous waste, invoking limits on the use of plastic bags, and demanding the restriction of illegal waste shipments.

Furthermore, the Commission proposed that “Member States develop national food-waste prevention strategies and endeavor to ensure that food waste in the manufacturing, retail/distribution, food service/hospitality sectors and households is reduced by at least 30 percent by 2025.” A very tall order which seems to focus mostly on the distribution and consumption side of the food system. The only explicit proposal that would directly affect production is the development of “a policy framework on phosphorus to enhance its recycling, foster innovation, improve market conditions and mainstream its sustainable use in EU legislation on fertilizers, food, water and waste.”

It is unclear to what extent the Commission will be able to bring these propositions to fruition in the present political climate, at a time when Union interventions are often met with suspicion if not outright criticism. The realization of these proposals may be perceived as entailing additional costs to producers and consumers at a time when Europe is recovering from a recession. Moreover, each Member State has a different degree of sensibility towards environmental and food production matters. However, the emergence of circular economic values in the language and perspectives of an important executive body is a feat of relevance in and of itself. It remains to be seen whether the general public, and national governments will embrace these ideas, and what policies will be adopted to make them accessible and understandable

Comments are closed.