by Fabio Parasecoli

from Huffington Post

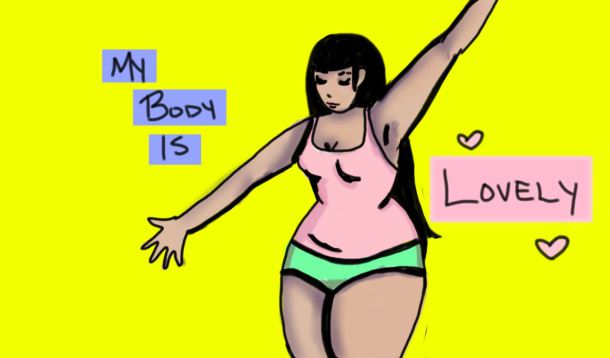

Why, as a society, do we care so much about the way we look? Why are we often uncomfortable with our reflection in the mirror? Too frequently, what we see does not match what the world around us promotes as acceptable or preferable. It is not only a question of clothing, hairstyles, or accessories. Our body itself frequently bothers us to the point where we end up perceiving it as some external burden imposed on our real self, that inner self that does not succeed in shining through the obtrusive flesh. We try our best to feel in control of our outer image. Enjoying total mastery over the body and its appearance is a powerful fantasy that can influence the way we manage ourselves on a daily basis, with health as our primary goal and often with looks as a secondary but not so irrelevant objective.

The image-obsessed media intensifies the relevance of these concerns, with a barrage of shows, news, books, magazines, and, more recently, even podcasts occupying our waking hours. But who decides what body images are appropriate, successful, and positive? How does mainstream culture adopt these images? Or rather, does mainstream culture actually create them? Why do they have such a strong clutch on our emotional wellbeing?

These elements are frequently not of our making. Popular culture has turned into a powerful repository of pictures, opinions, and customs that influence how we look at ourselves, the way we eat, and the whole economic and social system ensuring that we get the food we need on a daily basis. In fact, visual images at times filter our biological requirements (hunger) and psychological needs (desire). Desires, fantasies, and fears coagulate around us and in our bodies, deeply influencing us as individuals and communities. Moreover, images are never innocent or neutral: They always come entangled in a network of ideas and practices that are provided by our family, by the environment, by the culture in which we are born. The image of our body is never just that: In the eyes of the surrounding beholders, and as a consequence in ours, it is the representation of a man or of a woman, of a cute or of a not-so-cute person, of a strong or a weak individual.

In the U.S. cultural context, being overweight is often interpreted as a sign of lack of will and determination and as the external manifestations of emotional shortcomings. This element has had a profound influence on the way public debates about health and obesity — a contested concept in itself — have been framed, on how research on these issues has been conducted, and often on the policy measures adopted to deal with them. The very use of the expression “obesity epidemics” has been questioned. As I discussed in an earlier post, some critics now point to factors that for political, economic and cultural reasons are often underestimated or outright ignored, such as environmental toxins, pharmaceuticals, and overproduction in contemporary food systems. However, the mainstream discourse overall stigmatizes large bodies as the consequence of misguided personal choices, while interpreting them automatically as unhealthy and undesirable.

These are some the themes that will be examined in a public panel at The New School on Fat Studies, a new field that, in the words of scholars Sondra Solovay and Esther Rothblum, “questions the very questions that surround fatness and fat people.” How are notions of shame and disgust constructed and maintained? What power relations hide behind the very idea that people are expected to diet, even when they are healthy? What dynamics of exclusions are generated? Are there institutions, groups, or industries that gain from this state of affairs?

Whether we realize it or not, we learn discipline about food intakes by participating in a cultural system that gives our bodies meaning and makes them acceptable. They become part of practices and social arrangements that range from public health to nutrition, from visual culture to psychotherapy. Much more than can be covered in a panel discussion, but it is a start…

Comments are closed.