by Elin Hawkinson

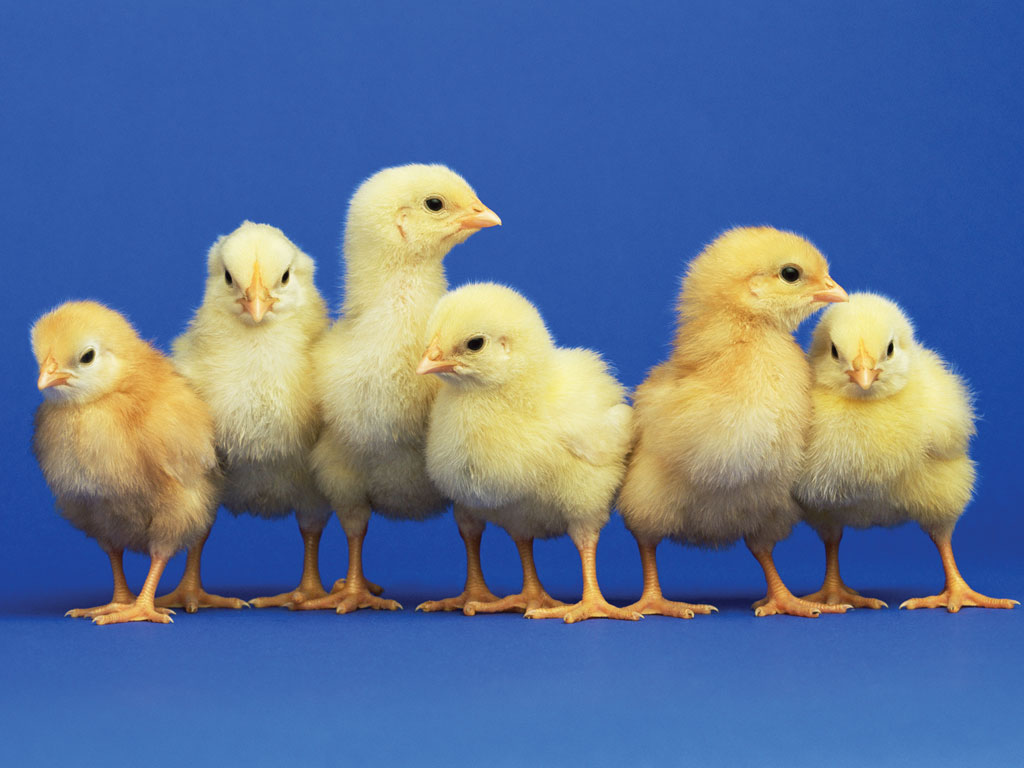

My fiancé ordered for me, and when the waiter brought the tall, metal spike mounted on a square of porcelain, threaded with baby chicks, I leaned over the wooden railing and vomited into the sand.

We were having dinner at a busy café on the very edge of the Mediterranean. The city of Netanya was spread out to the East, the sea and a feverish sunset to the West. My face still burned from the salted heat of the day.

The waiter hurried off for some water. My fiancé handed me his napkin, his forehead creased in a frown.

“What’s the matter? Are you sick?”

I licked my lips.

“Well? What’s wrong?”

The waiter returned with the water and I gulped it down while my fiancé offered apologies. He said something that made the waiter glance at me and laugh; soon they were speaking like old friends. I listened hard for any of the Hebrew words I knew. I didn’t hear them.

“Toh-dah,” I remembered suddenly.

They stopped laughing. I smiled weakly. The waiter addressed one final remark to my fiancé. The words were clipped, guttural, but that was no surprise. Even love sounded harsh in this language.

“What did he say?” I asked, after the waiter had moved off.

My fiancé began yanking at the wing of one of the chicks. It put up little resistance. I listened carefully for the snap of bone but heard only a moist tearing sound. He stuffed the wing in his mouth and chewed.

“Honey? What did the waiter say?”

In the waning light my fiancé’s deep brown irises darkened, swallowing the pupil. They appeared completely black. The alteration unsettled me.

“He said I should tell you not to say thank you so much.”

My fiancé was eating the other wing now. His teeth, unusually white, pierced the crispy skin with ease.

“What about the bones?” I asked.

“You eat them. They’re still soft. Look—” With his thumb and forefinger he dug into the wing, peeling back a strip of flesh. “Cartilage.”

My stomach roiled.

“I can’t eat that.”

He licked the greasy sheen from his fingers and sighed.

“You can. You just don’t want to.”

“I don’t want to eat a baby chick.”

“Don’t be stupid. They’re a delicacy. They’re like nothing you’ve ever tasted before.”

On my first night in Israel my fiancé’s friends threw a party in my honor at the kibbutz pub. My fiancé had seemed so proud, the smile never leaving his face, as we made the grand tour.

“She’s an actress. From New York City.” His friends behaved appropriately impressed. They hugged me. The women admired my dress. We all laughed about how no one could pronounce my name.

Late in the evening they began to reminisce about their days in the army. I found it difficult to make out all of the Hebrew but was content to sip anise-flavored liqueur while nestled in the crook of my fiancé’s arm. When the whole group burst out laughing, I plucked at his sleeve and asked to be let in on the joke.

He told me that the summer he turned eighteen, he and his friend Noa had been tank commanders on an abandoned airfield near the Gaza Strip. One day another young soldier, from Hadera, was driving the tank in the field for practice when he heard a scream and felt an odd bump beneath the wheels.

The young soldier recognized the scream; it was his best friend. Convinced in that moment that he had accidentally run over his best friend and killed him, he pulled out his government-issued rifle and shot himself in the head.

“And the funny thing,” my fiancé continued, “is that his friend wasn’t dead at all. He was fine. The tank driver had just run over his hand.”

I told him I didn’t think the story was funny at all. He stared at me as though he, too, couldn’t remember my name.

The waiter was at our table again, with a bill for my fiancé to sign. It seemed to me he used too much force; I worried the nib of the pen would bore through the thin paper. When he was finished he threw the pen down and excused himself to make a call.

I sat at the table with the remains of the wingless chick, tiny breast torn open. Somewhere inside lay the heart, cooked. The lungs. The gizzard. All the parts that I thought were supposed to disappear when a living creature became a piece of meat.

Elin Hawkinson is a NYC-based actress, editor and freelance writer whose work can be seen in Our Town/Downtown and the 2013 edition of 12th Street. She is a graduate of both The American Musical Dramatic Academy and The New School for Public Engagement.

Comments are closed.