by Maria Zizka

The public statement caused such a ruckus. “We are very much supportive of the family — the Biblical definition of the family unit,” claimed Chick-fil-A CEO Dan Cathy. Big name politicians, spiritual leaders, and sandwich-aficionados alike responded with attack or defense of Cathy’s beliefs. Though the fast food chief had previously generously donated to anti-gay marriage organizations, this public statement planted him conspicuously in breaking news headlines. For publishers, the challenge was deciding which section of the newspaper the scandal fit. Was it a food issue or a political statement? Did it concern economics or religion? The issues were too intertwined.

When Truett Cathy and his brother Ben opened an Atlanta diner called The Dwarf Grill (later renamed The Dwarf House) in 1946, they had no way of knowing that sixty years later, they would manage one of America’s largest family-owned businesses. The Cathy family opened the first Chick-fil-A in 1967, located in Atlanta’s Greenbriar Shopping Center, and then enjoyed a remarkable forty-four consecutive years of annual sales increases and franchise openings. Chick-fil-A proudly claims to be “the second largest quick-service chicken restaurant chain in the United States based on annual system-wide sales.”[1] Today, there are more than sixteen hundred Chick-fil-A restaurants in forty states. System-wide sales in 2011 exceeded $4.1 billion, which is a 13.08 percent increase from 2010.[2]

Impressive, as all Chick-fil-A restaurants are closed on Sundays.

The Cathy family maintains the importance of Sunday as a day of worship. From the very first Chick-fil-A restaurant, Mr. Cathy insisted on Sunday closure, a policy that both longtime and contemporary patrons appreciate.

Sunday worship isn’t the only Chick-fil-A policy that reflects the Cathy family’s conservative Christian beliefs. They also devote a percentage of profits (amounting to millions of dollars) to the community by donating to organizations such as the Pennsylvania Family Institute, a non-profit committed to promoting “traditional family values” and to stigmatizing same-sex marriage. Chick-fil-A donated over $2 million to anti-gay groups in 2010 alone. Additionally, in 1984, Truett Cathy created the WinShape Foundation (with the goal to help “shape winners”[3]). The foundation invests in Christian growth and ministry by supporting a variety of programs, including a summer camp, a long-term foster care program, a scholarship in conjunction with Berry College, and marriage enrichment retreats.

The WinShape Foundation always excluded same-sex couples from its marriage retreats, but the issue was not brought to public attention until this year. After Truett Cathy’s son Dan made his statement in The Baptist Press,[4] Chick-fil-A came under scrutiny, receiving attention from conservatives, liberals, and everyone in between political party lines.

The Supporters

One of first and loudest voices to defend Dan Cathy and Chick-fil-A was former Arkansas governor Mike Huckabee. When gay rights advocates urged a national boycott of Chick-fil-A restaurants, Mr. Huckabee used his television and radio programs to put out a call for Chick-fil-A supporters, even declaring (by unknown authority) August 1st to be Chick-fil-A Appreciation Day. On Facebook, more than 650,000 people signed up to participate. Many posted and “liked” photographs of packed Chick-fil-A restaurants.

Both influential politicians and average Joes actively continued the conversation about Chick-fil-A Appreciation Day on various social media platforms, including Twitter. Representative Michele Bachmann, Republican of Minnesota, tweeted a photo of herself at Chick-fil-A with the following text: “Ran into a hero outside @ChickfilA Thanks for your service, Colonel. http://t.co/CW6M9LWu.” Sarah Palin joined the conversation on Facebook by posting a photo of her visit to a Chick-fil-A in California. Others showed their support for the fried chicken sandwich fast-food chain as well. One woman, expressing her beliefs in freedom, tweeted: “I want to eat at Chick-fil-A because I believe in freedom of speech and religion – regardless of my stance on gay unions. (@divadoll123, 1 August 2012).” Still others explicitly confirmed Chick-fil-A’s religious beliefs and addressed how those beliefs aligned with their own. For example, “My Pastor @BishopPMorton took the Changing A Generation staff to Original Chick-Fil-A for lunch today! http://t.co/YjGloTKN (@GwendolynMorton, 1 August 2012)” and another “The Chick-Fil-A line. Imagine if believers showed up in numbers like these for all of the injustices of the world. http://t.co/yHS8tmO9 (@GeorgeERobinson, 1 August 2012).” It seemed that the entire country was talking about politics and religion through the vehicle of a fast-food restaurant.

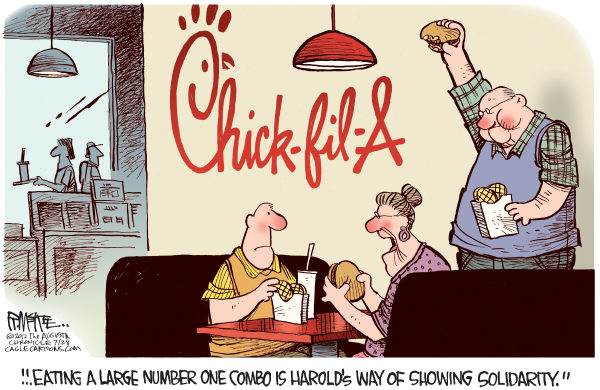

Supporters showed up in hoards, clogging Chick-fil-A drive through lines and creating long lunchtime waits at the quick-service restaurant chain. Statements made in person also revolved around religious conservatism and freedom of speech. Corlis Carter, who ate lunch at a Chick-fil-A in Marietta, Georgia proselytized, “If you are serious about your relationship with Jesus Christ, you just can’t be for same-sex marriage.” Mr. Carter went on to say, “Chick-fil-A has always been a family-oriented business. We’re just showing our support for them.”[5] Another advocate, Neil Greenlee, took it a step further by pledging to eat all three of his daily meals at Chick-fil-A on August 1st. “This is America, and we’re free to speak our minds,”[6] he argued. In support of Chick-fil-A, Americans exercised a new freedom: the freedom to eat where they choose.

The Opposition

Through protests and online platforms, liberals spoke out just as loudly against Chick-fil-A’s actions and the Appreciation Day organized by Mr. Huckabee. Representative Nancy Pelosi, Democrat of California and House Minority Leader, tweeted she was a Kentucky Fried Chicken fan. San Francisco Mayor Ed Lee was less nebulous in his Chick-fil-A disapproval when we tweeted, “Closest #ChickfilA to San Francisco is 40 miles away & I strongly recommend that they not try to come any closer. (@MayorEdLee, 27 July 2012).” One New York University student – Hilary Dworkoski – petitioned for her university to remove its Chick-fil-A franchise from the campus. Boston Mayor Thomas Menino[7] and Chicago Alderman Proco “Joe” Moreno[8] both promised they would try to block Chick-fil-A franchises in their respective cities.

The largest collective protest against Chick-fil-A occurred August 3rd, two days after Mr. Huckabee’s Appreciation Day. Supporters of same-sex marriage staged a “kiss-in.” At Chick-fil-A locations across the nation, couples posed for kissing pictures and held picket signs. Photos of kisses not chicken sandwiches flooded Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

The kiss-in encouraged gay-rights advocates to make statements regarding Chick-fil-A’s actions. Herndon Graddick, president of the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (GLAAD), evoked the concept of freedom of speech in a manner antithetical to the arguments made by Chick-fil-A supporters: “As a private company, Chick-fil-A has every right to alienate as many customers as they want. But consumers and communities have every right to speak up when a company’s president accuses them of ‘inviting God’s wrath’ by treating their L.G.B.T. friends, neighbors and family members with respect.”[9] GLAAD encouraged protesters to donate $6.50, the cost of a meal at Chick-fil-A, to gay and lesbian rights groups.

Some of the most innovative and hilarious responses to the Chick-fil-A scandal came from American cooks. J. Kenji López-Alt, a chef who writes a column called The Food Lab for the New York-based website Serious Eats, attempted to re-create the Chick-fil-A chicken sandwich at home. Included with the recipe, he wrote: “I don’t normally like to mix my food with my politics, but the thought of where my chicken sandwich dollars might be going is enough to leave a bad taste in my mouth, no matter how crispety-crunchety, spicy-sweet and salty that juicy chicken sandwich may be.” He admits how tasty he finds the Chick-fil-A chicken sandwich to be, but how it is not enough to set his moral principles aside for the sake of his taste buds. Another cook, Hilah Johnson, a YouTube Chef and Comedian, offered an alternative to the contentious chicken sandwich: the Chick-fil-Gay. “I love fried chicken sandwiches at Chick-fil-A,” she said in her video clip. “The problem is, I have a lot of gay friends, and I love them, too.” Her recipe contains “less sugar, less salt, and less funding for anti-human-equality organizations.” Even cooks, perhaps the population most easily swayed by desires of the tongue and belly, stood up for their beliefs and for the equality of all people.

The Repercussions

After Mr. Cathy’s initial comments, he later reiterated his stance on the Ken Coleman Show, saying: “I think we are inviting God’s judgment on our nation when we shake our fist at Him and say, ‘We know better than you as to what constitutes a marriage,’ and I pray God’s mercy on our generation that has such a prideful, arrogant attitude to think that we have the audacity to try to redefine what marriage is about.” The company’s positive perception among consumers has fallen sharply, says Ted Marzelli who manages the BrandIndex survey, an index of consumer good popularity.[10]

Though Cathy’s polarizing beliefs might seem to simply alienate liberal consumers, there is another fold of complexity at work here. It would be impossible to discuss the Chick-fil-A incident without addressing the deeply rooted concept of identity linked to Southern cuisine. Of all regions in the United States, the south can claim rights to one of the most intense and complicated social histories, one that is tied intimately with the local specialty dishes and the cultural practices surrounding food. Psyche Williams-Forson documents the importance of chicken to African-American women in the southern United States beginning in the slavery era and continuing to present times in her book, “Building Houses Out of Chicken Legs: Black Women, Food, and Power.” She outlines the intricacies associated with using food as a form of cultural work. Black culture, of course, has been negatively interpreted through racist chicken imagery, parodied by comedians like Chris Rock, and emotionally explored by artists like Kara Walker. Ms. Williams-Forson successfully demonstrates how Black women defy these representations and use chicken to exercise influence in food production and distribution. Concepts of feminism, too, are linked to cooking practices, as today women still perform the majority of food preparation and female identity, therefore, remains coupled with the tasks of the kitchen.

Fried chicken, in particular, is a foodstuff that holds many provocative and nuanced associations. It can be argued that African American slave women introduced fried chicken to the American South. They likely brought the knowledge and tradition from many West African cuisines, which fried poultry in fat, unlike the British who baked the birds. (Food historians also note Ancient Roman “fritters” but they were probably a sweet not savory dish. Still others point to Vietnam’s ga xao as the original fried chicken but most will agree that fried chicken truly became famous in the Southern United States around the slavery era.)[11] Seventeenth and eighteenth century texts largely ignore fried chicken recipes, even though the practice of frying chicken was well established by then, because many of those texts only documented the history and culture of white Americans. As Forson-Williams notes in her book, some slave women prepared and sold fried chicken to passengers on trains traveling through the south. In this way, these women were able to earn small amounts of money and also nourish their communities. Raising chickens happened to be one of the practices allowed by slaves on plantations.[12]

John T. Edge writes about the emotional weight and symbolism associated with fried chicken in his book, “Fried Chicken: An American Story.” In it, he traces the rich history of the beloved dish, moving from the windows of train cars stopped on railroad platforms to children’s shoeboxes and picnic baskets. Today, fried chicken is considered an iconic dish, one with a thorny history.

When fried chicken, among other foodstuffs like watermelon, and chitterlings, were utilized to defame Black cultural identity through humiliating blackface minstrelsy during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the regional dish came to be viewed in a pejorative way. And it still exists as a racial stereotype. In fact, just this year, Burger King received harsh criticism for a fried chicken wrap commercial that portrayed negative stereotypes. Fried chicken remains a contentious subject, even given its adoration and ubiquity throughout the United States, especially in the American South.

There is yet another touchy subject in the mix: Southerners tend to feel like the only defeated Americans and are, consequently, both fiercely loyal to southern institutions (like Chick-fil-A) and commonly defensive when put down. During the middle of the last century when Truett Cathy founded Chick-fil-A, it was an era that Marcie Cohen Ferris calls “the coming of age of a new South”[13] when Southern states industrialized and became part of modern America. While industrial progress pushed Southerners forward, many clung to their Southern identity, helping maintain a certain fondness and celebration for Southern foods such as fried chicken.

Dan Cathy’s public statement crossed political, cultural, and social lines, just as the Cathy family’s biblically-based management practices of Chick-fil-A, namely the large-sum donations to anti-human equality organizations, affect immediate supporters, all Chick-fil-A patrons, and even the greater American public. These donations counteract the efforts of gay-rights advocates in the United States, if not directly hurt same-sex couples, because channeling money from Chick-fil-A profits — dollars and cents spent by citizens spanning gender, ethnic, and socio-economic differences — fund organizations like the Pennsylvania Family Institute in working to prevent human equality and hinder marriage rights. The Cathy family has every right to any creed they choose but, when they force said creed upon their customers, their issue becomes our issue. How we decide to respond aligns us with politicians, religious leaders, and even YouTube chefs. The Chick-fil-A fried chicken sandwich seems to stand suddenly on the battlefield in the gay-marriage cultural war when, in fact, all our foods have always functioned as cultural weapons—as both tools of destruction and construction.

[1] Chick-fil-A website: “S. Truett Cathy.” 3 September 2012.

[3] Chick-fil A website: “WinShape Foundation.” 3 September 2012.

[4] Blume, K Allan. “‘Guilty as Charged’, Cathy Says of Chick-fil-A’s Stand on Biblical and Family Values” Baptist Press: July 16, 2012.

[5] Severson, Kim and Robbie Brown. “A Day for Chicken Sandwiches as Proxy for a Cultural Debate” New York Times: August 1, 2012.

[7] “Mayor’s Letter to Chick-fil-A” The Boston Herald: 20 July 2012.

[8] Dardick, Hal.“Alderman to Chick-fil-A: No Deal” Chicago Tribune: 25 July 2012

[9] Preston, Jennifer, Robbie Brown, and Kim Severson. “Gay Couples Head to Chick-fil-A for a Kiss-In Protest” New York Times: 3 August 2012.

[10] Severson, Kim and Robbie Brown. “A Day for Chicken Sandwiches as Proxy for a Cultural Debate” New York Times: August 1, 2012.

[11] Mariani, John F. “The Encyclopedia of American Food and Drink.” (Lebhar-Friedman. New York: 1999,) p. 305-6.

[12] Forson-Williams, Psyche. “Building Houses Out of Chicken Legs: Black Women, Food, and Power.” (Univ. of North Carolina Press: 2006.)

[13] Severson, Kim. “A fast food Loyalty rooted in Southern Identity.” New York Times: 2 August 2012.

Maria Zizka is a Berkeley-born food writer and cook, currently working with chef Suzanne Goin in Los Angeles. She is pursuing a Master’s degree in Food Culture and Communications at L’Università degli Studi di Scienze Gastronomiche in Italy. At home, she brews beer with her Dad and tends a little garden.