We can learn something – actually quite a lot – about our culture by looking at how we imagine the future of food. Are we all going to starve, as Malthus prophesied back in the eighteenth century? Or will we find ways to feed the growing humankind? And what kind of resilience will we embrace? Will it be based on science and technology, or will it rather rediscover the ways of our ancestors? As Warren Belasco indicated in his masterly Meals to Come: A History of the Future of Food, these scenarios are far from objective and neutral. They are rather the expression of ideologies and political negotiations that are solidly rooted in our present and our evaluation of the societies in which we live.

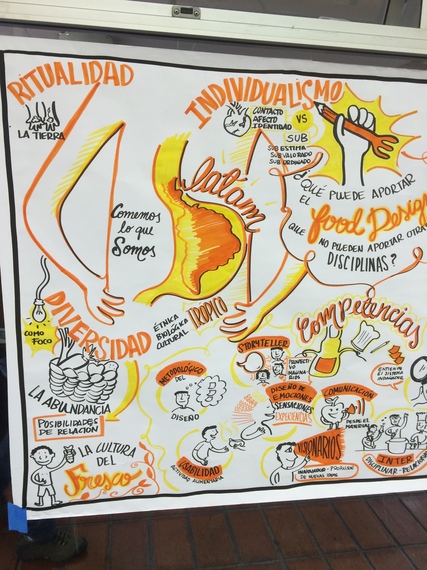

As I have already discussed in this space, a relatively new voice has joined this conversation: food design. Design as a discipline is very much focused on the innovation we can introduce in our daily lives. As designer Todd Johnston observed, “A design marks out a vision for what can be; the act of designing is to move with intent to close the gap between existing conditions and that vision.” Back in 1999, design theorist Tony Fry famously considered design as a weapon against defuturing, that is “the condition of undermining viable human futures through our contemporary modes of habitation.”

As food becomes increasingly central in how we imagine ourselves and the world, it is inevitable that design expands its sphere of interest and practical applications to food. Food design, as the founding document of Food Design North America states, “includes any action that can improve our relationship with food individually or collectively. These actions can relate to the design of food products, materials, practices, environments, systems, processes and experiences.” The relevance of the reflection about what’s coming is highlighted in a Kickstarter campaign that is raising funds for MOLD: The First Print Magazine About the Future of Food.

Food Design, the book written by design critic Ed van Hinte on and in collaboration with Katja Gruijters, is a stimulating addition to this conversation. Its subtitle, “Exploring the Future of Food,” excludes nostalgia and luddist perspectives from being considered as effective tools to make our food system better. Technology is not considered an enemy, but rather a possible collaborator, even when it is not necessarily at the center of Gruijters’s work.

The volume follows a well-proven approach: an issue in food systems is identified and discussed, and then Gruijers’s projects dealing with it – directly or indirectly – are presented, illustrated by photographs of events and objects. Among the topics, we read about seaweeds, flowers and insects as underused sources of nutrition, proteins from plants, the need for surplus reduction in Western food production, obesity and health. While the narrative structure is quite effective in introducing many hot topics, the authors do not claim to have any final solution. They are actually quite self-reflective about it, musing: “Another weakness in some of our prophecies is that they themselves can cause changes. They can enhance conditions or hamper them.” Debating the future is, in fact, highly political.

Changing the way people eat, their preferences and their outlook is not supposed to be easy. Food design is not about coming up with quick fixes. Van Hinte and Gruijters underline that “it is important for designers and food providers to be aware that their work is never a one shot deal, certainly not when it comes to ecological interventions. Balance is not a fixed state.” However, looking for viable solutions does not necessarily mean renouncing pleasure. “The new field of food design is emerging as a way to shed light on the development of food values in terms of nutrition, enjoyment, and seductiveness to all the senses.”

Food waste inevitably looms large in the pages of the book. It has emerged as one of the most glaring problems in post-industrial societies, becoming increasingly unacceptable in terms of food justice, environmental impact, and long-term sustainability. For that reason, at The New School we decided to partner with the Institute of Culinary Education to organize Zero Waste Food, a two-day conference that will take place on April 28 and 29 in New York City. Aspiring to bridge the separation between theory and practice, the conference will connect academics with practitioners, designers, chefs, and the business sector through panels and hands-on application. We are particularly looking forward to the keynote address by Massimo Bottura, whose restaurant Osteria Francescana in Modena, Italy, reached the no. 1 position on The World’s 50 Best Restaurants list and whose non-profit Food for Soul aims to empower communities to fight food waste through social inclusion.