by Jennifer Baily

Food writing has exploded over the last few decades, with more and more acceptability of it as a career and genre. This is of course positive to those who are interested, yet in some cases due to high exposure on the internet and television reality shows, there are no lines between professional and hobbyist.

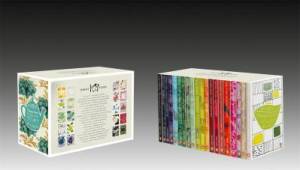

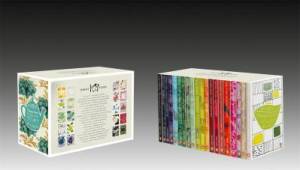

The Penguin Great Food series is a recent collection of twenty authors throughout the last 400 years. Each edition is a selection of writings from each author’s major works over their careers, and in some cases a collection of their essays. The editions are available individually, or as part of a beautifully boxed set which are worth the investment for the interested reader. Each book is gorgeously covered in artwork based on patterns of pottery or china, in theme with its contents by artist Coralie Bickford-Smith, and it appears she read each one to find its core. Each edition is embossed with raised images and calligraphy by artist Steven Raw. This attention to detail and beauty make them hard to resist, especially for a reader such as myself, trying to rebel against e-readers and internet publications. They are items to be kept, collected and cherished.

To me, this collection slyly reminds us that this kind of writing is not new, and is most certainly not a fad influenced by television shows, Michelin stars or one’s ability to photograph each meal. The series is a vast historical food writing collection including domestic manuals, essay collections, recipe collections and food memoir. Authors vary between the well known to the slightly obscure, yet it is clear to see how each author was chosen for their knowledge of a cuisine, their passion for food, for cooking or for a combination of all. They appear to have been chosen for their impact on culinary history at large, and for their influence over those who would come to follow them, whether it is in food writing, or as culinary leaders in the kitchen.

The well-known; Elizabeth David’s collection A Taste of the Sun, in which David heralds the delights of the Mediterranean including a glorious section named ‘Useful Advice’ firmly explaining how to set up a kitchen. MFK Fisher’s culinary essays and prose in Love in a Dish are choice cuts of her intimate reflections on life and food and how they are intertwined. The excerpts from Alexandre Dumas’s Grand Dictionnaire de Cuisine in From Absinth to Zest is of course beautifully written, but also an astute culinary dictionary that weaves in his memories and eccentricities perfectly. 19th century essayist Charles Lamb is here, as is Calvin Trillian, the acclaimed New Yorker journalist.

And others, though not as well known to me, offer astute insights into what was a far greater impact on food writing and culinary history than seen at first glance. Dr A.W. Chase, a physician whose self-published books became household bibles in the 1850’s and who was a great influence to Elizabeth David; Colonel Wyvern, who on returning from serving in the British Army in India opened a cooking school in Britain and encouraged the nation to merge British and Indian cuisines and use of spices.

The series as a whole is an amazing meditation on the history of food over numerous continents and generations. Hannah Glasse’s 1747 writings are directed towards teaching servants skills of the kitchen in a casual and fuss-free way, followed by the precision by which Isabella Beeton in the 1860’s attempted to clarify the particulars of running a household to the mistress of the house. We then see Claudia Roden’s revolutionary Middle Eastern musings from the 1960’s alongside the formidable Alice Waters, whose contributions to food culture in the 2000’s cannot be denied. In some cases, these authors were writers first and food lovers second. In other cases they were chefs or homemakers, turning into accidental literary masters. But in all cases the writers were able to take the simple act of eating or sharing food with others and make it a meaningful and passionate experience.

The series as a whole is an amazing meditation on the history of food over numerous continents and generations. Hannah Glasse’s 1747 writings are directed towards teaching servants skills of the kitchen in a casual and fuss-free way, followed by the precision by which Isabella Beeton in the 1860’s attempted to clarify the particulars of running a household to the mistress of the house. We then see Claudia Roden’s revolutionary Middle Eastern musings from the 1960’s alongside the formidable Alice Waters, whose contributions to food culture in the 2000’s cannot be denied. In some cases, these authors were writers first and food lovers second. In other cases they were chefs or homemakers, turning into accidental literary masters. But in all cases the writers were able to take the simple act of eating or sharing food with others and make it a meaningful and passionate experience.

It seems to me the most interesting part of this collection and their authors is the different lifestyles and lives they lead, whether it be a chef and confidant for Gertrude Stein such as Alice B. Toklas, or Isabella Beeton; a new housewife aiming to help others in the setting up and running of a household; or more exotically a great Victorian chef at the front of the Crimean War trying to feed British Troup’s with a little more panache, as in the case of Alexis Soyer.

Brillat-Savarin, a man who took writing about food to a deeper and almost philosophical level, most certainly was correct in his well known notion from The Pleasures of the Table; ‘Tell me what you eat and I will tell you who you are’. This is certainly reflected in the different social standings of the authors and their very different reflections on eating in this series. But in many ways I find more strength and poignancy in his lesser known belief that ‘The world is nothing without life, and all that lives takes nourishment’, as it reaches deeper into what I feel is reflected in this collection; the vast differences of the subjects are overarched by its commonality. We all must eat. This collection proves that although wars may be fought, cuisines may change and writers may fall in and out of favour, those who write about food may become as timeless as their subject.

The collection boasts essays, recipes, memories, advice and everything in between; the thread that connects them all is food. Yet in some ways the entire collection is not for the general home recipe reader or food channel watcher. This collection requires dedication, love and a sense of humor. By this I mean, the author’s works have been slightly edited but only in choice of work, not in tone. Some of the editions are dense and written in the style of their time- whether it be 1920 or 1720. One must remember the authors were writing at very different times and a bit of light heartedness must be exercised when reading such works as The Well Kept Kitchen, published in 1615 and written by Gervase Markham, whose chapter on ‘The Inward Virtues of Every Housewife’ lists (among other things) that she must be religious, temperate, dress well, know all herbs and cook more ‘from the provision of her own yard than the furniture of the markets’. Or in A Little Dinner Before the Play, the collection of recipes and advice from Agnes Jekyll from the 1920s, ‘No one likes to be fat; it is unbecoming, fatiguing and impairs efficiency.’

To me, this is not a negative of the collection, as I love to have a little insight into the intricacies of daily life that are different to my own, but at times I found some writers harder to read than others. For example, Samuel Pepys’ diary The Joys of Excess on its own would have irritated me, as it is diary entries simply from a man who loved to drink so his head ‘aked’, but as part of the collection added to its character. This is purely a warning and not a negative; for some editions, the insight is into lives led in very different times. In many cases the food is a backdrop for the historical, the anthropological and in many ways, biographical.

The recipes then of course can be hard to follow with unknown ingredients and techniques, such as Hannah Glasses’ recipe for turtle. This is to be expected, as they were created decades, even centuries, ago but this again is not a complaint simply a caution. In some cases many of the recipes are easy to understand and timeless; Isabella Beeton’s Christmas Cake or Bubble and Squeak though created in 1860 appear clear, confidant and worth a try.

My only criticism is that each volume is in most cases a selection of writings by each author from a greater work or from their entire career. To me, there is little description as to why particular pieces were chosen, or why some more famous pieces from an author where not. Each has a succinct Penguin-style cover blurb and author biography but for me, as it is such an epic collection combining the familiar and the obscure, I would have liked a little more information as to the reason for the choices or regarding the author.

As a box set, with a price again not for the light food buff, but for the serious connoisseur, a little more information again as part of or extra to the purchasing of the box. It seems to me this would be purchased by someone who is yearning for all there is to know about food history and writing, and this in some ways can fall short. The reality is, I am sure, that the editing floor contains many of the tidbits I would like. Correlating, editing and publishing an anthology such as this is no small task.

This is a historical collection like no other. I cannot think of another topic in which this could occur- writers whose work spans continents, generations and social standing, all in one place with each voice as strong as the next.

Jennifer Baily is a lover of food and writing and combining the two whenever possible.

Foods We Hate, I didn’t quite realize the range in picky eating. I had often referred to myself as a picky eater, the kind of person that only likes good food. Of course I qualified the word good by saying things like healthy, local, organic, or even just tasty. In Stephanie Lucianovic’s book she attempts to determine why kids, and “finicky eating” adults, decide not to eat foods based on looks, taste or feel. Why do we have strong aversions to certain foods and, while we’re at it, what is succotash?

Foods We Hate, I didn’t quite realize the range in picky eating. I had often referred to myself as a picky eater, the kind of person that only likes good food. Of course I qualified the word good by saying things like healthy, local, organic, or even just tasty. In Stephanie Lucianovic’s book she attempts to determine why kids, and “finicky eating” adults, decide not to eat foods based on looks, taste or feel. Why do we have strong aversions to certain foods and, while we’re at it, what is succotash?