1

Let me tell you something: climbing a mountain builds character. On top of that, I believe that every young person should climb at least one mountain around puberty. It will teach all sorts of important skills [e.g., to increase spatial awareness, to maneuver tricky physical spaces, to hone a healthy fear of death, to increase an appreciation of trail mix and Good Old Raisins and Peanuts (GORP), and of course, to accurately sharpen the rage against whatever authority in their young lives made them climb that fucking mountain in the first place.

Better yet, if you are a young person, climb a fucking mountain with a parent, relative, or mentor! That way you’ll be able to take note of this older person’s mortality lay bare—perhaps, as in my case, for the first time since the moment of my own birth. While I don’t remember experiencing my own birth, it certainly happened because there are photos and stories and well, I’m here. Hearing my dear mother curse in disbelief that we had ever stepped foot on Mount Monadnock in New Hampshire with my CCD group from Holy Name Church in West Roxbury, Massachusetts was life changing. It was informative to witness her struggle up and around weird boulder formations and to see her slide down the face of the mountain on her tush as she encouraged me to do the same by example.

First of all, our parents are supposed to be models of behavior. If she could do it, I had to at least try. My mother has not the patience of Job. Instead, she has the impatience of a comedian who truly loves to complain by cracking jokes and giggling and talking shit about the priest who led us there. When confronted with her own mortality, she transforms from a nice devout Catholic woman into an observational comedian: think lovechild of George Carlin and Joan Rivers. Sigmund Freud once wrote that all jokes are about either sex or death. Well, these jokes were all death. It was almost as if by joking about dying and dangers, my mom was preventing us (me and whoever else would listen) from giving up. This was ever more helpful to me than Father Sughrue and his giant walking stick. We get it, you’re supposed to be the shepherd, and we’re the sheep! A little on the nose?

2

Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau adored Mount Monadnock. They couldn’t get enough. Emerson loved it so much he wrote the poem “Monadnoc,” and some consider it his most famous poem. Galway Kinnell wrote “Flower Herding on Mount Monadnock,” which you can find in full here. In this poem, Kinnell’s speaker laughs at himself and considers his own death. If death is the great equalizer, then a mountain is death’s doorstep with all its dangerous charms.

1

I can support it no longer.

Laughing ruefully at myself

For all I claim to have suffered

I get up. Damned nightmarer!

It is New Hampshire out here,

It is nearly the dawn.

I, too, stood on its peak, which was absent vegetation or trees due to two fires set many years ago. The first fire was set by settlers in 1800 in order to make room for pastures for farming. Twenty years later, settlers set it on fire again because of wolves. But this second fire turned into a devastating one. Things went out of control. This fire lasted weeks and spread up the peak, taking off the soil and removing the chance of anyone farming on it for a long, long while. However, because the mountaintop is without trees, the view is just stunning.

Galway Kinnell may have also believed that he was going to die on Monadnock when he wrote this:

3

The last memory I have

Is of a flower that cannot be touched,

Through the bloom of which, all day,

Fly crazed, missing bees.

And saw his own death in his reflection:

6

I kneel at a pool,

I look through my face

At the bacteria I think

I see crawling through the moss.

My face sees me,

The water stirs, the face,

Looking preoccupied,

Gets knocked from its bones.

7

I weighed eleven pounds

At birth, having stayed on

Two extra weeks in the womb.

Tempted by room and fresh air

I came out big as a policeman

Blue-faced, with narrow red eyes.

It was eight days before the doctor

Would scare my mother with me.

We both climbed the same mountain. And there he goes, talking about the moment of his birth (see the first and second paragraphs of this piece), and his own mother. I see you there, Galway Kinnell.

3

On this peak, Father Sughrue said a quick mass, gave us communion and a vanilla “inspirational” sermon about overcoming obstacles. He wanted the very fact that we had made it to the top of the mountain to serve as a metaphor for achievements and our relationship with Jesus Christ. Something about Jesus being with us on that peak. For a moment on the top of the mountain, I felt slightly intoxicated with a sort of victory—I was a rat to Sughrue’s Pied Piper: I was on the top of a mountain!!!!!!!!! This high wore off quickly after my mother deadpanned that the communion, this body of Christ we consumed/ate, would also be our Last Supper as we likely would never make it to the bottom of the mountain to the group’s bus or to safety. She vividly described our dad and little sister blissfully unaware of our present peril while they enjoyed the warm creature comforts of our home in Roslindale. Maybe Jesus was back home with them too: we couldn’t see him on that peak.

Saying the thing that was true lightened the atmosphere. In that moment, to state that we felt in a little bit of danger was funny and necessary because that was the truth. We needed to hold on to something. The ground was not secure or even, but laughing was stabilizing for us. Of course we made it down the mountain. We made it home, but the world was much bigger and more hilarious than it was when I had awoken that morning.

4

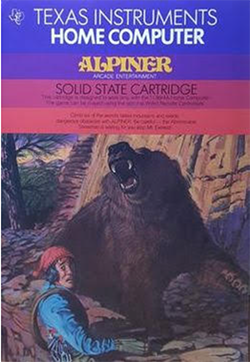

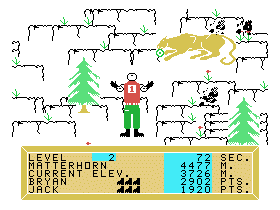

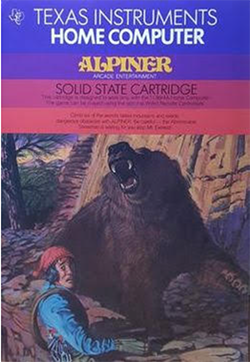

As a child I played a Texas Instruments Home Computer video game called Alpiner.

When I set out to write this, I wanted to argue that I had prepared myself to climb Mount Monadnock through my mastery of this old video game. But that would be massively fallacious reasoning. Playing Alpiner prepared me for only one thing: playing more video games. Climbing the mountain, however, prepared me for life, nuance, and even responsibility. It also, as I think is clear, gave me a new appreciation of my mother, whose humor radiated when fussing over her mortal coil.

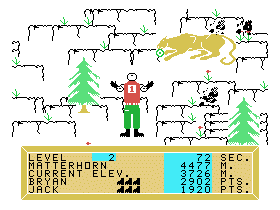

After selecting the option to play Alpiner alone, I slowly selected the three letters in my first name (A, M, Y) by toggling a joystick and pressing an orange button. Then I set a course up a mountain. A digital version of the classical piece Peer Gynt by Edvard Grieg played as I climbed. I viewed my avatar from behind: third person—as a whole figure who could see his entire surroundings. (The avatar was always male.) Falling rocks were avoided by jamming the joystick hard right or hard left. A bear would appear in the distance and would always remain in the same space so could thereby be avoided quietly and quickly. Same for mountain lions and snakes and trees. The only hazard difficult to avoid were the skunks, which would appear quite suddenly misting a red net of dots toward my “guy.” This net was hard to miss.

A skunking is not fatal, but it always sends you to the bottom of the mountain.

Has a skunk ever sprayed you in your life? No. Me neither.

One night my mom smelled a skunk while driving in the car or during a walk or while we were hanging out in the backyard. She said “I don’t mind the smell. I kind of like it.” I believed her.

The world was, indeed, always much more interesting when something was actually happening. I also thought it was fun to imagine taking a bath in tomato juice, the only cure known to me for a skunking in my limited understanding of the natural world. What if our showers rained red juice? What if the slanted walking condition portrayed in V8 commercials could only end with a red bath? I’ve never been sprayed by a skunk in my waking life, so I still don’t know what it’s like to sink into a cold tomato juice bath.

But I have come to know what it is like to bleed and feel blind rage at the same time, for I am a woman in a body. I shed blood on a monthly basis. For me, a brief, spiritual rage precedes each monthly bleeding. It is not a rage at anything/anyone (i.e., it is not directed at anything or anyone), which makes it ever more terrifying and curious. It is a rage that craves an object, and when it finds no object is shelved. My rage is like a skunk on an abandoned mountaintop looking for climbers. Krista Tippett, host of the On Being podcast, once said in an interview that “anger is often what pain looks like when it shows itself in public.”

To put it another way, a skunk in a video game is what pain looks like.

When I read Homer’s Iliad senior year of high school, I gave intense and curious side-eye to the rage of Achilles. When Achilles’ best friend Patroclus was murdered by a Trojan fighter named Hector, Achilles flew into a rage. He was so angry at Hector that he told him “my rage, my fury would drive me now to hack your flesh away and eat you raw – such agonies you have caused me.” That’s serious brotherly love. This rage consumed him with such a totality that Achilles compared the object of his anger to another object: a meal he would consume in a cannibalistic fury. See, he’s so “consumed” by the death of Patroclus symbolically, he says he might as well eat the guy who he blames for his death in order to bring the whole thing to a sort of completion.

No, Achilles did not eat Hector. He killed him. And after he killed him, he dragged the corpse around attached to the back of his chariot defiantly for many days like tin cans on the back of newlywed couple’s car. Those newlyweds want you to hear their tin cans. Achilles wanted everyone to see Hector’s corpse. Achilles was like a skunk on the mountain in Alpiner in his own way. He aimed his wrath at anyone who messed with his territory (e.g., his best friend).

In Alpiner, the skunking seemed to be a consistent response to the mountaineer’s presence as an intruder on the mountain. Unlike the bears, snakes, mountain lions, and rocks, which exist on their own regardless of the player, the skunk and its scented anus secretions seemed to be aware of my avatar’s presence. If I stayed off the mountain, if I didn’t play the game, if I stayed inside reading a good book, I would be safe from a skunk’s red netted orb of rage.

I just Googled “How to Get Rid of Skunk Smell” and it appears that there are many, many treatments. I’m good at Googling things. Tomato juice isn’t even on the list; in fact, it is said to just cover up the smell and does not actually clean a body of a skunk’s spray, which can cause nausea, vomiting, and short-term blindness in humans. I’ve got nothing in my anus as powerful.

If you really want to get the stink of a skunking off yourself, try mixing hydrogen peroxide with apple cider vinegar and some water and dish soap. Shampoo your whole body with this mixture. Shampoo your whole body like you’re not yourself.

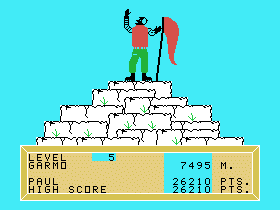

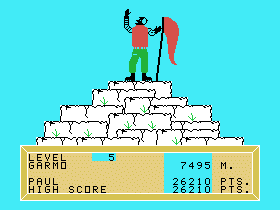

In Alpiner, you progressed the chapters in the game from mountain to mountain the way any professional mountain climber’s career would. You started with the mountains of lowest elevation and you progressed with experience. You started with Mount Hood (11,249 feet), then Matterhorn (14,692 ft), then Mount Kenya (17,057 feet), then Mount McKinley (now called Denali) (20,310 ft), then Mount Garmo (21,637 ft), and finally Mount Everest (29,029 ft). Once you successfully climbed Everest, the game was over. The glitchy digital Peer Gynt “music” crescendoed again in volume: but not to tell you that danger is present, but to concede that triumph was yours. You won! You’re on the top of a mountain!

I could Climb Mount Hood in approximately ten seconds.

I practiced a lot and did indeed climb to the top of this digital Mount Everest. I have no recollection of playing the game after that fine achievement. While it felt pretty good to reach the peak, in doing so my hunger for playing this game was satiated with finality.

Did you know that sometimes when a person actually dies climbing Mount Everest, no one comes to get the body? Did you know there are some corpses up there in the peaks there totally frozen? If the dispatchers can, they talk to you on your walkie talkie until your voice fades, your breath becomes shallow, and you die. Every search party costs something (the time and energy of those looking for the lost, money, resources), and the risk of additional human life is often not worth it. Would you want others to risk this treacherous trip only to also die–just to allow your loved ones to reclaim the frozen husk of your corporeal form? You’re an angel dancing through the gilded gates of heaven strumming tunes on your shiny new harp, what do you care? You’re clinking champagne flutes with Satan in hell, what do you care?

In Alpiner, when you aim your character to the side end of the screen (perhaps to avoid falling rocks), the avatar disappears off screen for a moment, only to appear on the other side of the screen. This kind of thing would never fly in 21st century video games. Yeah, when you disappear, you just appear again nearby. Continuity errors like this remove a suspension of disbelief the game’s creators had, I guess, failed to cultivate.

In Back to the Future Part 2, Marty McFly has to avoid seeing himself during the “Enchantment Under The Sea Dance” while securing the Sports Almanac from Biff because one version of himself is already playing guitar on stage. If the two Martys ever, by chance, saw each other, something horrible would happen. When I look in the mirror, my goal is to not dislike whatever it is that I see, so I can only imagine the horrors of seeing a time traveling version of myself! I would happily slip away stage right with a hat over my face only to reappear stage left with my hat in hand.

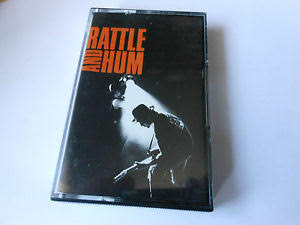

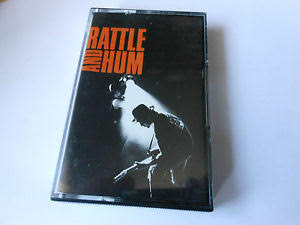

I won my sixth grade Geography Bee at Holy Name School in West Roxbury, Massachusetts by identifying the second highest mountain in the world (it’s K2). This won me a copy of Rattle and Hum by U2 on audio cassette.

I carried Rattle and Hum home proudly. My parents were proud and excited. They loved and love rock and roll. I had never heard of U2 in my life up to that point, but they sure had. We listened to a few tracks together as I recounted my victory, and then I squirreled away the double cassette tape set into my bedroom and played it on my tiny red cassette deck. One song U2 covered called “Helter Skelter” boomed. It was messy. I liked it. I didn’t know that this was a cover of a Beatles song or of Charles Manson’s culty appropriation of the term to explain away the brutality of his violence.

When Paul McCartney wrote the song, the term “helter skelter” in UK slang meant “disorderly haste or confusion.”

When I imagine taking a V8 shower, I think of the film Carrie and the prom scene: all the blood and the bullies. When I think of bullies, I think of Charles Manson convincing his Family to do horrible bullshit. I think of the greatly pregnant dead Sharon Tate and her blood pressed first into fingertips and then into the arcs and lines of blood to form the word Pig written on the door.

Pig.

I refuse to make sense of someone (Charles Manson) using rhetoric (say, like the performative utterance as popularized by J.L. Austin) to make things, horrible things happen.

I read the nonfiction book Helter Skelter by Vincent Bulgosi and Curt Gentry about Charles Manson and the Manson family while commuting on the bus from my parents’ house in Roslindale to Boston University one summer for my summer job. The bus pulled wide high hilly turns in Brookline as my stomach pitted at the violence of Manson’s life. Manson took the phrase “Helter Skelter” from the Beatles song. The house Sharon Tate was murdered in by Manson’s family was situated in a deep ravine called Benedict Canyon. Benedict Canyon was created by rainwater dripping over a tremendously long period of time and runs north to south.

5

I am pretty fearful of new climbing experiences because I am afraid of heights. When I am on the edge of a cliff, or the top floor of a skyscraper, even one rung up a stepladder, or the edge of a subway underpass, the edge of a ravine or canyon, my inside forearms tingle painfully, and I become lightheaded. When invited to rooftop shindigs I stay near a wall, facing as far away from the edge as possible. I avoid looking at the ground below. Otherwise I am haunted by an imaginary seamstress touching and pressing thousands of pins and needles into my forearms: that’s how it feels to be afraid of heights.

As I sat far away from the edge of a naturally formed cliff in Ireland on a trip right after college, my friends who did not have a fear of heights sat right near the edge. It wasn’t one of those famous cliffs that people send postcards about or meaningfully name-check in Irish folk songs. This cliff was just some random not-too-steep locale. When my friends approached the edge, I watched them. Physical pain overcame my body. I was fearful of their deaths and of something horrible happening. Why couldn’t I just sit there and enjoy all the shades of green: a particular beauty I’ve thought of many times since? My brain is hardwired to avoid cliffs; my brain thinks they’re dangerous.

In that moment, I could have used the right joke. Know what I mean? But my mom was nowhere to be found to provide levity. You know, I could have just really used a good joke that reminded me that, sure I was a mortal entity, but that I was also temporarily in the safe harbor of a sunny field overlooking a cliff.

Some moments can be constellated back to different experiences: these are partially traceable and yet unwilling to be precisely held. As an adult you know that no one is fully protected from the meaninglessness and cruelty of the world at large.

But the only image that my brain could conjure while I sat near that cliff was a large adult skunk appearing out of nowhere and just hosing my friends and I down off the cliff and into the wild below with some Carrie-like fury in a skunk’s version of anguish.

This is pretty funny now, but I remember it as only pure terror. And, as I learned playing Alpiner, there is nothing to be done when a skunk hoses you. You just start over.

Amy Lawless is the author of two books of poems including My Dead (Octopus Books). Her third poetry collection Broadax is forthcoming from Octopus Books this summer. A chapbook A Woman Alone is just out from Sixth Finch. With Chris Cheney she is the author of the hybrid book I Cry: The Desire to Be Rejected from Pioneer Works Press’ Groundworks Series (2016). Her poems have recently or are forthcoming in jubilat, Reality Beach, The Volta, Washington Square Review, Best American Poetry 2013, and the Academy of American Poets’ Poem-a-Day: 365 Poems for Every Occasion, and the Brooklyn Poets Anthology (Brooklyn Arts Press). She received a poetry fellowship from the New York Foundation for the Arts in 2011. She lives in Brooklyn.

Amy Lawless is the author of two books of poems including My Dead (Octopus Books). Her third poetry collection Broadax is forthcoming from Octopus Books this summer. A chapbook A Woman Alone is just out from Sixth Finch. With Chris Cheney she is the author of the hybrid book I Cry: The Desire to Be Rejected from Pioneer Works Press’ Groundworks Series (2016). Her poems have recently or are forthcoming in jubilat, Reality Beach, The Volta, Washington Square Review, Best American Poetry 2013, and the Academy of American Poets’ Poem-a-Day: 365 Poems for Every Occasion, and the Brooklyn Poets Anthology (Brooklyn Arts Press). She received a poetry fellowship from the New York Foundation for the Arts in 2011. She lives in Brooklyn.

feature image via Tim_Johns.

Sabrina Hayeem-Ladani is a native New Yorker, poet, and multi-genre performer. Her work weaves poetry, dance, and song to explore themes of love, family, grief, and what it means to human. She has performed across the United States, as well as in Europe. Sabrina’s poems can be seen in various publications such as in the anthology So Much Things To Say: One Hundred Poems of Calabash (Akashic Books), and The Wide Shore, a journal of global women’s poetry. She currently resides in Brooklyn.

Sabrina Hayeem-Ladani is a native New Yorker, poet, and multi-genre performer. Her work weaves poetry, dance, and song to explore themes of love, family, grief, and what it means to human. She has performed across the United States, as well as in Europe. Sabrina’s poems can be seen in various publications such as in the anthology So Much Things To Say: One Hundred Poems of Calabash (Akashic Books), and The Wide Shore, a journal of global women’s poetry. She currently resides in Brooklyn.

Donovan McAbee’s poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Five Points, Tar River Poetry, The Christian Century, and a variety of other journals. He lives in Nashville, Tennessee with his wife and newborn son and works as Associate Professor of Religion and the Arts at Belmont University. You can also find more of Donovan at

Donovan McAbee’s poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Five Points, Tar River Poetry, The Christian Century, and a variety of other journals. He lives in Nashville, Tennessee with his wife and newborn son and works as Associate Professor of Religion and the Arts at Belmont University. You can also find more of Donovan at

Holly Rice is a creative writing MFA candidate at The New School and the Deputy Editor of the Inquisitive Eater. She is the 2015 recipient of the Nova Scotia Talent Trust’s RBC Emerging Artist Award and lives in Williamsburg. Her book reviews can be found in Boog City and on PublishersWeekly.com.

Holly Rice is a creative writing MFA candidate at The New School and the Deputy Editor of the Inquisitive Eater. She is the 2015 recipient of the Nova Scotia Talent Trust’s RBC Emerging Artist Award and lives in Williamsburg. Her book reviews can be found in Boog City and on PublishersWeekly.com.

Jack McKenna is a New School student expecting to graduate with his MFA in Creative Writing in May 2017. Previously he completed his undergraduate at the University of Pittsburgh in 2014, majoring in English Writing and Music Composition. He has read his work frequently at The Salon Series, The KGB Bar, and at student readings. The recent shift to weirdness in his writing is largely the fault of the excellent advice of his thesis advisor, Shelley Jackson. This is his first publication.

Jack McKenna is a New School student expecting to graduate with his MFA in Creative Writing in May 2017. Previously he completed his undergraduate at the University of Pittsburgh in 2014, majoring in English Writing and Music Composition. He has read his work frequently at The Salon Series, The KGB Bar, and at student readings. The recent shift to weirdness in his writing is largely the fault of the excellent advice of his thesis advisor, Shelley Jackson. This is his first publication.

Amy Lawless is the author of two books of poems including My Dead (Octopus Books). Her third poetry collection Broadax is forthcoming from Octopus Books this summer. A chapbook A Woman Alone is just out from Sixth Finch. With Chris Cheney she is the author of the hybrid book I Cry: The Desire to Be Rejected from Pioneer Works Press’ Groundworks Series (2016). Her poems have recently or are forthcoming in jubilat, Reality Beach, The Volta, Washington Square Review, Best American Poetry 2013, and the Academy of American Poets’ Poem-a-Day: 365 Poems for Every Occasion, and the Brooklyn Poets Anthology (Brooklyn Arts Press). She received a poetry fellowship from the New York Foundation for the Arts in 2011. She lives in Brooklyn.

Amy Lawless is the author of two books of poems including My Dead (Octopus Books). Her third poetry collection Broadax is forthcoming from Octopus Books this summer. A chapbook A Woman Alone is just out from Sixth Finch. With Chris Cheney she is the author of the hybrid book I Cry: The Desire to Be Rejected from Pioneer Works Press’ Groundworks Series (2016). Her poems have recently or are forthcoming in jubilat, Reality Beach, The Volta, Washington Square Review, Best American Poetry 2013, and the Academy of American Poets’ Poem-a-Day: 365 Poems for Every Occasion, and the Brooklyn Poets Anthology (Brooklyn Arts Press). She received a poetry fellowship from the New York Foundation for the Arts in 2011. She lives in Brooklyn.