My first blood sausage was in Alsace, in a cellar restaurant, a sort of medieval cave with a warped stone floor and walls. Months later the man I was there with, an American like me, would no longer be my lover.

Blood sausage. Boudin, the French call it. Black pudding, the English say, where it’s thickened with oats for breakfast. A mixture of blood and pig fat encased in the very same pig’s intestine. Ours arrived on a large plastic plate with a dollop of mustard and sauerkraut, not nearly as dark or bloody or sinister as expected.

At the wine bar near my house, in Denver, I’ve witnessed some terrible first and second and third and fourth dates happen, despite its being an otherwise warm and lovely place. Small and shadowy, hardwood floors, with mismatched comfortable sofas and chairs that carve out little alcoves, elegant ferns and mirrors, two low-hanging, theatrical chandeliers (one crystal, the other copper), with music of mostly jazz or standards playing in the background, some watery, vaguely Japanese prints mounted in gilded frames, plus curves of wrought-iron everywhere, it’s a place where the young and aspiring come to have their bright hearts broken.

I’ve been coming recently to write, to drink the house red when it’s on the cheap, and to sample its meat and cheese platter. My waitress, a long-haired blonde in her twenties, bored, no doubt a Marley fan, sets it down beside my empty glass. It’s an ample, if fairly predictable array: a wedge of Roquefort, a local goat, a few pale shavings of something hard, some slices of common salami and speck. There’s a scattering of almonds, a small bowl of olives, and a ‘homemade’ (the menu informs me) baguette, perhaps five to six inches long. I’ve been to this wine bar plenty, eavesdropping on the heartsick as I whittle away at a poem, but this is the first time I’ve ordered what the place calls charcuterie.

I’m keeping a tiny notebook, and this place I give two stars out of five.

Back in November I said to Neal, one morning in bed, One of my goals this year will be to master charcuterie. (We host lots of dinner parties, and Neal falls in love with me again when I announce, with such conviction, odd, spontaneous goals.) You do that, baby, Neal said. And the comment has justified several jaunts to local pubs and restaurants (for research, I say) and also garnered me (for Christmas) two cheese-knife sets, my own slate board (with chalk and a large glass dome), and a set of small, handsome stabbing forks and spoons. Neal, a Jew and mostly vegetarian to boot, knows how to encourage a guy.

Once, in Rome, many years ago – with the American from Alsace – I gorged on the real thing: a smorgasbord of variegated, veined and fatty slices, some slinky and nearly see through, some wine-cured, smoked and deeply red, seductive coins of various size, others pickled, others seemingly perfectly raw with large, glistening pockets of fat, a slab of chilled duck liver terrine, all of which came served on a massive wooden board with elegant swipes of mustard, an earthenware jar of chutney – piquant, a jalapeno-pear – and a generous wedge of (get this) weeping honeycomb. It was pricey, and it had me quivering. It came with a basket of crackers and delicate rounds of toasted rye, but decidedly zero cheese. There are purists – I see them as sad people really – who reserve the term charcuterie to mean a “meats-only” affair: from the French ‘chair’ ‘cuit,’ or cooked flesh. They’re the type of people who get ticked when you holler out answers to Wheel of Fortune.

Google “authentic charcuterie” some night, and you’ll see what I mean: exactly like porn, the pink and crimson fans of meat unfold, busy wisps and entanglements; the gelatinous, angular blocks of pate; the silky ribbons of fatty prosciutto; the long, slender rows of circle cuts of boar or deer or, more dangerously, pheasant and even quail, although pig remains the standard, and here and there, because we remain a civilized human people, an apricot or bit of roasted tomato nestled in.

Growing up in small-town Texas, I often encountered colossal platters of unwavering meats and cheeses, deli slices of turkey and ham rolled up like neat cigars, the orderly cubes of cheddar and Swiss piled up on kale (before we called it kale) in a starburst pattern surrounding a shallow dish of store-bought Ranch. I loved that shit; I really did. My mother was a part-time caterer in the 80’s, which means our house was often supplied with food intended for other people, people wealthier than us, leftovers from their weddings and graduations and funerals. Nothing that fancy really, tubs of chicken or crab salad, pre-cut dinner rolls, cocktail shrimps wallowing in Tupperware containers.

But open the fridge some Saturday morning to find a picked-over cold cut tray? For me and my sisters and brother, chomping away to morning cartoons, such stuff was paradise.

Denver is far, far away from that dusty, distant farming town, and these days, with our worship of celebrity chefs and consumer-centric apps like Yelp, the pressure is on, in a wicked way, for restaurateurs to keep up with our ever-expanding palettes. We have restaurants here masquerading as butcher shops, with names like Cow and Knuckle, and while we don’t pick our actual pig out from a sty for our bacon yet, I can imagine we some day might. We’ve got a competitive marketplace for sausage, too; you can get smoked practically anything now: goose, elk, venison, goat, the usual suspects like trout or buffalo, plus ostrich studded with cranberries, or rattlesnake with flecks of sage. And while pot shops and local breweries have them beat out by a long shot, our exotic cheese shops are right behind. There’s a place near our house (five stars on Yelp) where Neal and I get often procure this outrageously aged Gouda, calcium crystals galore, that simply numbs the tongue.

For a long time, Denver boasted only a single hand-cranked sausage joint. It sells charcuterie, too, of course, and it’s a fairly decent place, with exotic poutines and long wooden tables the likes of which you’d expect to find in a German biergarten. The first time I ate there, one late afternoon, was with another local poet. It was a weeknight happy hour, and the poet and I were on our way to getting very happy. We hardly knew each other. He was famous, and I was not, but a bit of very sweet poetry news had happened to come my way, and the poet had kindly reached out to me on purpose. I’d heard from innumerable people that he was a generous, smart, if imposing man, bald with enthralling, deep blue eyes, and also thoroughly gentle.

The poet was known for his love of meat, particularly barbecue. And his poems about the Civil War, I deeply admired. A white guy, after all!

When our third beers arrived, we were hungry, so decided to split the sausage sampler. It features a blood sausage, and it’s served with an in-house pickle mix and a set of exotic mustards. It’s actually overwhelming and a great deal masculine.

“Have you eaten blood sausage before?” the poet asked.

“Sure,” I said. “Once, in Alsace, though I barely remember it.”

“Close your eyes and think of cinnamon. Think ginger snap more than iron. Don’t think about blood at all. It’ll be softer than you expect.”

He was right.

Blood sausage, served either hot or cold, is as soft as morning sand. You can’t even call what you do with your teeth biting down exactly. It’s more like simply giving in, like sliding into water.

Seven weeks later, the poet, getting dressed one night for a holiday party, would complain of a mild headache to his wife. He would ask his wife for some Advil, and she’d go and fetch him some, and hours later, at the party itself, he would complain to the hosts of an awful dizziness. He would collapse, is how I’ve heard it told, and be dead from a stroke, a blood clot to the brain, en route to the hospital. He was 40.

The art of blood sausage (some call it a science), that is, of preserving meat in its blood, dates back some 6,000 years, and reveals a history of people trying to counter unavoidable loss. In several Asian cultures, it’s a sign of reverence. No part of the slaughtered animal should simply go to waste. In Mongolia, where Genghis Khan made it law that the blood of the killed thing remain preserved, they rely on sheep primarily. In China, it’s known as ‘red tofu,’ and the congealed blood (typically duck) is cut and served in tiny squares, similar to aspic. In Tibet, they use mostly yak, the complex preparation of which approaches the ceremonial.

So, too, with charcuterie more broadly. An intimate, splendid affair.

My current goal to master it has led me not just to many pubs but also toward actual research. The university where I teach owns, quirkily enough, one of the world’s largest collections of cookbooks. There are lots of old books to slog through, bright photos from the 60’s and 70’s when hand-carved radishes and tomatoes decorated your standard meat-cheese tray. The 30’s and 40’s and 50’s seemed obsessed with jellied loaves. And of course there were soft-cheese balls, cream cheese and Blue cheese blended together, sculpted into pineapple shapes and covered in slivered nuts. But there are older hints, too, of salt embargos (a key ingredient, after all), of tribal sausage wars, not to mention religious dietary rules and regulations, the need to keep dairy away from meat, and government restrictions. In the 15th Century, for instance, the French government had to isolate fisheries from butcher shops, and creameries from both, in order to stave off cross-contamination and prevent the foodborne illnesses that were rampant at the time.

Imagine a charcuterie today where the meats didn’t nestle up against the cheeses, where the vinegars didn’t leak a bit into the currant jam.

I’ve been practicing on friends. What I’ve learned is that texture matters – any cheese expert will tell you that – as do color, shape, and size, the balance of sweet to smokiness, the balance of acid to spice, and height. Mason jars of pickled beans and blanched asparagus (which happen to double perfectly, my friend Adrienne told us all, as Bloody Mary spears). Chunks of pecorino floating like icebergs on puddles of honey. A pale gray trout terrine. Wedges of bloomy rinds.

Olives and nuts are a given, of course.

And the homely cherry pepper, which I love.

Cheeses wrapped in chestnut leaves. Just the smoke of them.

Why not grapes? Grapes, the poor, forgotten things.

Manchego and quince paste on rosemary skewers.

Fried chickpeas!

Gherkins. Gherkins.

The triple creams.

This weekend, I want to smoke radishes, I whisper to Neal in bed.

He’s asleep already; he barely stirs.

And the meats?

The meats. My Christ. Don’t get me started.

David J. Daniels is the author of Clean (Four Way Books, 2014) winner of the Four Way Books Intro Prize and finalist for the Kate Tufts Discovery Award and the 2015 Lambda Literary Award for Gay Poetry. He is also the author of two chapbooks, Breakfast in the Suburbs(Seven Kitchens Press, 2012) and Indecency (Seven Kitchens Press, 2013), selected by Elena Georgiou as co-winner of the 2012 Robin Becker Chapbook Prize. David teaches composition in the University Writing Program at the University of Denver.

David J. Daniels is the author of Clean (Four Way Books, 2014) winner of the Four Way Books Intro Prize and finalist for the Kate Tufts Discovery Award and the 2015 Lambda Literary Award for Gay Poetry. He is also the author of two chapbooks, Breakfast in the Suburbs(Seven Kitchens Press, 2012) and Indecency (Seven Kitchens Press, 2013), selected by Elena Georgiou as co-winner of the 2012 Robin Becker Chapbook Prize. David teaches composition in the University Writing Program at the University of Denver.

feature image via Locale.

Leslie’s poetry has been awarded a National Society of Arts and Letters Chapter Career Award, the David E. Albright Memorial Award, and was chosen by D. A. Powell as the recipient of the 2014 Washington Square Poetry Award. Her poems were also finalists for the 2014 49th Parallel Poetry Award and the 2014 New Letters Poetry Award. She received her MFA from Indiana University and is currently a fellow at the Fine Arts Work Center. Above all, she enjoys lemonade in clear cups and jackalopes.

Leslie’s poetry has been awarded a National Society of Arts and Letters Chapter Career Award, the David E. Albright Memorial Award, and was chosen by D. A. Powell as the recipient of the 2014 Washington Square Poetry Award. Her poems were also finalists for the 2014 49th Parallel Poetry Award and the 2014 New Letters Poetry Award. She received her MFA from Indiana University and is currently a fellow at the Fine Arts Work Center. Above all, she enjoys lemonade in clear cups and jackalopes.

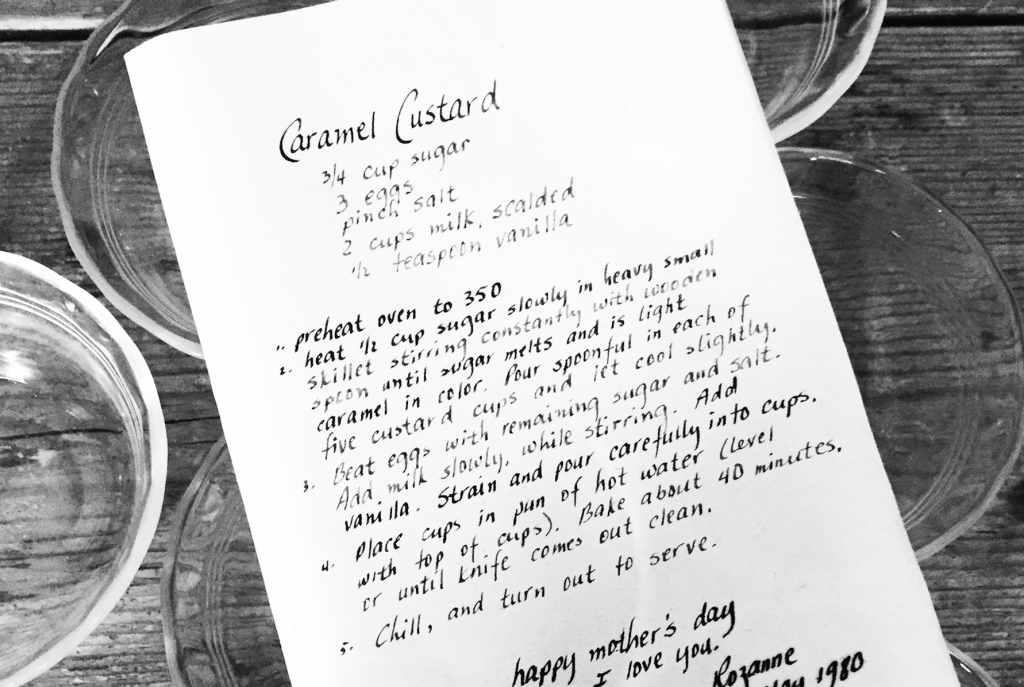

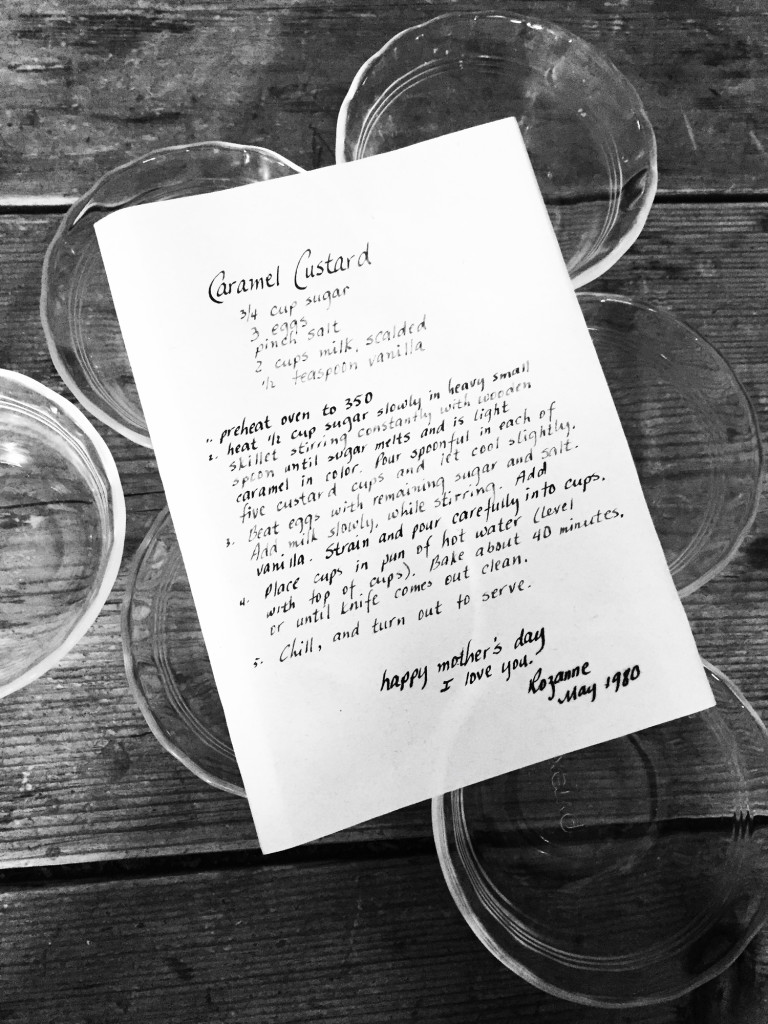

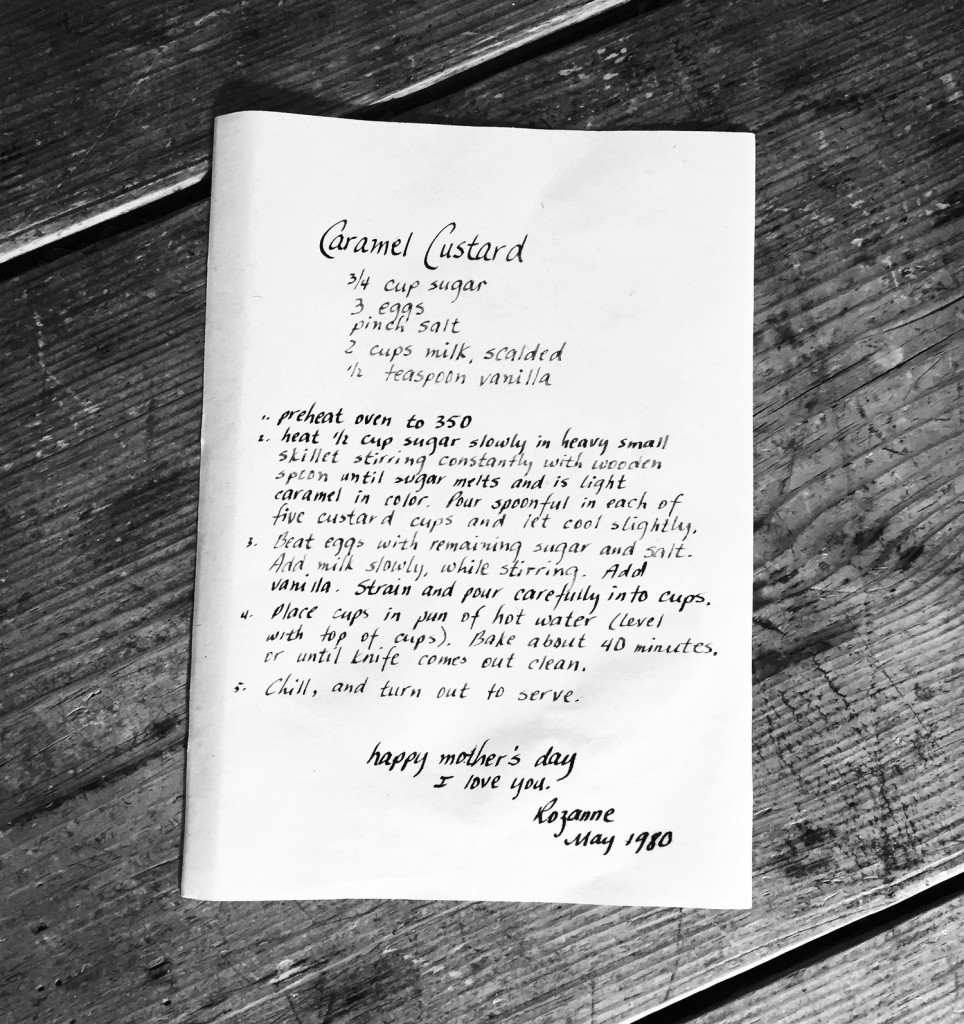

Rozanne Gold is a renowned chef and award-winning food writer. Author of thirteen cookbooks, including the internationally-translated Recipes 1-2-3 series, Rozanne’s writing and recipes have appeared in The New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Gourmet, Oprah, Bon Appetit, FoodArts and More. She is currently a guest columnist for Cooking Light and blogger for the Huffington Post. Considered “the food expert’s expert,” Rozanne has helped create some of the country’s most enduring food trends. Between meals, Rozanne is an end-of-life doula, philanthropist, and poet.

Rozanne Gold is a renowned chef and award-winning food writer. Author of thirteen cookbooks, including the internationally-translated Recipes 1-2-3 series, Rozanne’s writing and recipes have appeared in The New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Gourmet, Oprah, Bon Appetit, FoodArts and More. She is currently a guest columnist for Cooking Light and blogger for the Huffington Post. Considered “the food expert’s expert,” Rozanne has helped create some of the country’s most enduring food trends. Between meals, Rozanne is an end-of-life doula, philanthropist, and poet.

Brett Rawson is a writer and runner based in Brooklyn, New York. He is co-editor of

Brett Rawson is a writer and runner based in Brooklyn, New York. He is co-editor of

David J. Daniels is the author of Clean (Four Way Books, 2014) winner of the Four Way Books Intro Prize and finalist for the Kate Tufts Discovery Award and the 2015 Lambda Literary Award for Gay Poetry. He is also the author of two chapbooks, Breakfast in the Suburbs(Seven Kitchens Press, 2012) and Indecency (Seven Kitchens Press, 2013), selected by Elena Georgiou as co-winner of the 2012 Robin Becker Chapbook Prize. David teaches composition in the University Writing Program at the University of Denver.

David J. Daniels is the author of Clean (Four Way Books, 2014) winner of the Four Way Books Intro Prize and finalist for the Kate Tufts Discovery Award and the 2015 Lambda Literary Award for Gay Poetry. He is also the author of two chapbooks, Breakfast in the Suburbs(Seven Kitchens Press, 2012) and Indecency (Seven Kitchens Press, 2013), selected by Elena Georgiou as co-winner of the 2012 Robin Becker Chapbook Prize. David teaches composition in the University Writing Program at the University of Denver.