By Allison Scola

Cannoli, the symbol of Sicilian sweets, are favored by “townspeople, by the middle class and by nobles, [and] desired by rich and poor alike,” wrote ethnographer Giuseppe Pitré in his Usi e Costumi, Credenze e Pregiudizi del Popolo Siciliano, Vol. 1.[i] Although Pitré focused his research and scholarship on folk traditions in Sicily during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, today, a century after the tens of thousands Sicilians immigrated to the United States, Pitré’s statement still rings true: love for cannoli is undying. Yet Italian cannoli and Italian American cannoli have distinct differences.

It is impossible to determine where cannoli were first made.[ii] However, historically, their origins are attributed to ancient times. In Sicily, pastries are strongly connected to annual rituals. For example, cassata, a ricotta cake presented in the form of a disk—the shape of the sun—is attributed to Easter, a holiday that marks rebirth; i.e., the start of the agricultural planting season when the sun begins to warm the earth again and days are longer. Another example is Minna di Sant’Aita, a small ricotta-cream cake with a candied cherry on top that is presented in the form of a woman’s breasts. Minna di Sant’Aita is meant to commemorate the martyrdom of Saint Agatha whose breasts were amputated in retaliation by her persecutor, a Roman prefect whose advances she shunned. It is traditionally eaten for the feast day of Saint Agatha, celebrated annually in early February in Catania. In this same vein, cannoli used to be the traditional dessert of the carnival season.

Carnevale, as Carnival is known in Italian, is the period before the start of Lent which generally falls at the end of February and the beginning of March. Since Roman times, Carnevale was a period “…of excess, when social order went topsy-turvy, and wild parties, balls, and parades were organized.”[iii] Celebrated by practicing the rites of the Greek god of ecstasy and wine Dionysus (or Bacchus, as he was known in Roman cults), carnival marked the end of the old year and the beginning of the new. In Southern Italy and Sicily during these wild days before Ash Wednesday, masques were worn to hide revelers’ identities allowing them the freedom to do whatever was pleasurable. The celebrations promoted “an orgiastic lack of control”[iv] as well as the consumption of foods in excess before Christian worshipers abandoned animal meat for Lent.

Cannoli, with their fried shells—often made with sweet wine to add a distinct flavor—are symbolic of Carnevale’s carnal and culinary debauchery. As Salvatore Farina supposes in his book Sweet Sensations of Sicily: “Probably, long ago, in the wild days of the Saturnali and the old style Carnival, street sellers prepared cannoli in the noisy and crowded public squares, filling the shell with ricotta and honey cream. This confection that comes in natural portions is ideal for eating outside, just as one does today with an ice cream cone.”[v]

“Outside” because after the solitary cold days of winter, Sicilians were thrilled to engage in their social passeggiata ritual and thankful to welcome warm weather, longer days, and the Earth returning to a fertile state. Just as the Minna di Sant’Aita are symbolic of Saint Agatha’s breasts, the form of cannoli—a hard cylinder with white cream filling oozing out its ends—represents male genitalia: not only symbolizing the orgiastic rites of human worshipers, but also the cultivation and fertilization of the earth for the planting season.

Pitré collected this Sicilian folksong about the cannoli di Carnevale[vi] that is rampant with double entendre.

| Beddi canola di carnilivari, megghiu vuccuni a lu munnu un ci nn’eè su biniditti spisi li dinari, ogni cannolu è scettru di ogni Re; arrivunu li donni a disirtari; lu cannolu è la virga di Moisé cui nun ni mancia si fazza ammazzari, cui li disprezza è un gran curnutu affé |

Lovely Carnival cannoli nothing better in the world money is well spent, every cannolo is a scepter to every King; they drive women to distraction; the cannolo is the rod of Moses who doesn’t eat it should be killed, who disdains it is a great cuckold |

Sicilian cuisine, when referring to savory dishes such as Pasta alla Norma (Pasta with Eggplant and Tomato Sauce) or Pasta cu pisci spata e amenta frisca (Pasta with Swordfish and Mint), is somewhat simple. Recipes are often limited to three main ingredients. In contrast, colonial occupations of many different cultures over three millennia provoked elaborate desserts.[vii] The Greeks introduced wine, and the Romans introduced honey. The Arabs imported cinnamon and introduced jasmine extracts. Sugar arrived during the 14th century and replaced honey as the principal sweetener. In the 16th century, the Spaniards brought chocolate from the New World, and in the 18th century, the French noble class introduced elaborate banquets and refined dining. After the unification of Italy, northern European noble families introduced butter, cream, and new preparation techniques. All the while, over the past two hundred years, nuns adopted and perfected the art of baking pastry in order to generate funds to finance their convents and support the orphans in their care.[viii] Each culinary innovation contributed to the evolution of cannoli, from an ancient fried pastry-shell filled with sheep milk ricotta and honey-cream to a more elaborate and refined culinary delight.

Each city in Sicily has its own concept of how cannoli—the shell, the cream, and its confections—are prepared. When tens of thousands of Sicilians immigrated to the United States from the mid-19th century to the mid 20th century, they brought their fondness for cannoli and their varying recipes with them.

As a result, not surprisingly, the recipes of modern Italians and of Italian Americans vary. The most notable differences

exist in the ingredients exploited and in the preparation and the customs surrounding consumption. As with many Italian versus Italian American recipes for a dish of the same name, the availability of ingredients determines these differences.

Overall, the recipes for the cannoli shells vary in four distinct ways: The type of wine used (or in some cases, wine vinegar), whether or not cocoa is used instead of cinnamon, whether or not shortening is used in place of butter, and whether or not eggs are used. Furthermore, there is a distinction between the shape the baker cuts the dough in preparation for wrapping it on the cylinder: a circle, a diamond, or an oval.

For the cannoli cream, the biggest distinction between the Sicilian and Italian American recipes is the type of cheese: sheep milk ricotta versus cow milk ricotta, and in some cases Italian Americans supplement the ricotta with mascarpone cheese (a cheese hailing from Lombardy, in the north of Italy) and perhaps even whipped cow milk cream. Other distinctions regarding the preparation of the cream include how long the cheese and sugar mixture is left to rest in the sieve before adding any other flavoring, and aside from vanilla, which other ingredients are added. These additional ingredients are often considered “secret,” in order to distinguish one’s recipe from other bakers.

Pietro Buttitta (my second cousin), a retired, Palermo-trained pastry chef who founded and owned Conca d’oro pasticceria in Rome for over thirty years, shared with me his cannoli recipe and his experiences with the culture of cannoli from both his birthplace, Bagheria, Palermo and his adopted home thirty minutes by metro from the center of Rome. Growing up as a young boy, Buttitta worked in his uncle Domenico Cuffaro’s famous Bagherese establishment Bar Aurora, a social hub for adults and teenagers after World War II that he called, “Il salotto di Bagheria (The salon of Bagheria).” At fourteen years old, he started his formal training as a pastry chef in Palermo.

Now in his 70s and retired, Buttitta’s basic cannoli recipe is as follows:

Shell: Flour (1 kilogram), confectioner’s sugar (100 grams), shortening (50 grams), cocoa (15 grams), white or red wine vinegar (100 grams), and water (200 grams).

Mix all ingredients in a bowl adding water to the mixture a little at a time until it becomes a sticky dough. Knead mixture into dough. Leave it to rest in the refrigerator for one hour before rolling it into thin sheets with flour and a rolling pin. Cut the dough into ovals. Wrap the dough ovals around steel cylinders, sealing the dough ends with water. Fry the dough cylinders in peanut oil for 3-4 minutes. Remove, and let cool. (Note: Peanut oil is an American product developed in the late 19th century. It is preferred by many chefs for frying because of its high smoke point.)

Cream: Sheep milk ricotta (1 kilogram), confectioner’s sugar (500 grams), vanilla extract (a pinch), chocolate chips (500 grams).

Mix the ricotta, sugar, and vanilla. Allow it to rest for one hour, then mix again. After an hour, sieve the mixture overnight in the refrigerator using cheese cloth and a fine colander to drain the liquid out of it. Before serving, mix in chocolate pieces.

Preparation: After filling the shells with the cream, decorate the ends with candied orange, and powder with confectioner’s sugar.

Buttitta’s clientele in Rome purchased cannolifor major holidays, on weekends for family dinners, and for festive

occasions all year long. He recalls that even as a young man, once refrigeration existed, cannoli would be eaten all year. (Before refrigeration, consumption of cannoli was limited to spring and early summer when the sheep produced milk and farmers made ricotta, generally (according to my cousin Tanina Buttitta, 69, Buttitta’s sister-in-law, and a native of Bagheria), late February, March, April, and May (therefore, coinciding with the start of Carnevale and leading up to the warmer months of the year)). Pietro explained that cannoli mignon or miniature cannoli are a new phenomenon only established in the last 20 years. Furthermore, he does not condone chocolate dipped shells because it changes the flavor too much. Chocolate dipped shells are also a newer phenomenon.

Giusto Priola is the co-owner and pastry chef at Cacio e Vino restaurant in New York City’s East Village. Priola is from Palermo and is in his 40s. The big distinction between his recipe and Pietro Buttitta’s recipe is that Priola uses Marsala wine versus vinegar in his shell recipe, together with cinnamon and a little espresso. Priola is the only person I encountered who uses espresso. He also uses peanut oil to fry the dough. When I spoke with him, he commented that making the shell is very difficult, and in Sicily, very few pastry shops make them more than once a week because it is so labor intensive. Pietro Buttitta also commented, “Non è facile” (It’s not easy…) to make the shells.

To achieve an authentic Sicilian cannolo, Priola imports sweetened sheep milk ricotta from Le Delizie Antica Pasticerria Siciliana in Aragona, Sicily to make his cream filling. Gennaro Picone, the Lipari, Sicily-born, chef-owner of Gennaro restaurant on Manhattan’s Upper West Side also reported that he too imports sheep milk ricotta from Sicily to achieve the cannoli he serves in his restaurant.

A recipe that I often consult when making cannoli cream is that of Giuliano Bugialli from his book, Foods of Sicily and Sardinia and the Smaller Islands. Different from the recipes above, Bugialli’s shell recipe calls for butter and dry white wine. For the filling, like the other Sicilian-trained chefs, sheep milk ricotta is the primary ingredient; however his recipe does not call for vanilla, but orange extract and jasmine extract. Bugialli’s recipe is the only recipe I encountered that calls for jasmine extract—which may be dubbed his “secret ingredient.” He also recommends, when possible, to include candied pumpkin in the cream.[ix] Pietro Buttitta said that candied pumpkin is an ideal addition to the cream, but extremely difficult to find, even in Sicily.

Still, of the Sicilian chefs, everyone has a different concept of how to decorate the ends of their cannoli: Some bakers add additional chocolate chips, some add only orange rind, and others add pistachio bits and orange rind or orange rind and a maraschino cherry. Each baker has his own execution.

The origins of cannoli in the United States can be traced to the immigrants who came from Campania and Sicily starting in the mid-19th century and who settled in New York, New Orleans, Philadelphia, Boston, Chicago, and Wisconsin, to name a few locales. Ferrara Pasticceria in New York’s Little Italy at the corner of Grand and Mulberry Streets was founded in 1892 and claims to be “America’s Oldest Pasticceria.” The founder, Antonio Ferrara was not a pastry chef, but a businessman from Avellino, Campania who sought to create a gathering place for post-opera patrons. Today, Ferrara’s display case teams with cannoli already filled with cream in the traditional size and shape, about 5 inches long, alongside miniature cannoli, which are about 3 inches long. Both sizes are offered with chocolate-dipped shells.

Ferrara’s cannolirecipe is posted on their website, www.ferraracafe.com. Different from the Sicilian-trained chefs cited above, Ferrara uses red wine and butter in their dough recipe, and their cream filling, according to a woman I spoke to at the café, is made with cow milk impastata ricotta from Calabro’s World of Cheeses based in East Haven, CT.

Impastata ricotta is a drier, more delicate ricotta that is preferred by chefs for making sweet pastries and stuffed pastas such as ravioli and manicotti. In the New York area, Calabro’s is the preferred supplier of impastata ricotta by the chefs with whom I spoke for this article. Calabro’s makes its ricotta from fresh, Vermont cow milk using a 100 year-old artisan cheese making tradition.

Ferrara’s cream recipe is as follows:

3 lbs. ricotta cheese

3/4 cup confectioner’s sugar

1/4 cup crème de cacao or other sweet liqueur

3 tbsps. grated bittersweet chocolate

2 tbsps. finely minced, candied orange peel

1/2 cup chopped pistachio nuts for garnish

Ferrara’s recipe uniquely cites crème de cacao or another kind of sweet liqueur to be employed in the filling.

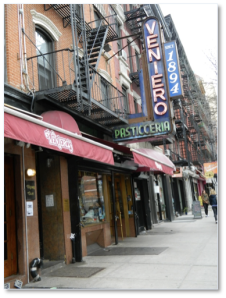

Veniero Pasticceria is located between First and Second Avenues on East 11th Street in New York’s East Village, which one hundred years ago, was a predominantly Sicilian enclave. Veniero was founded in 1894, and throughout its history, has won many awards for its cannoli and other pastries. Like Ferrara, Veniero offers an assortment of regular-sized and miniature cannoli, both

traditional presentation and chocolate covered.

The pastry chef with whom I spoke over the phone uses cow milk ricotta for his cream recipe. Although he was not willing to share much more information with me, when asked, he did say that at Veniero they use nutmeg oil in their filling. This revelation is most interesting because nutmeg oil is particular to New York City cannoli—more specifically, cannoli from Veniero and shops located in Brooklyn. When conducting research regarding cream recipes, I read a series of posts on Chow.com’s Chowhound Home Cooking Board. A discussion titled, “Seeking the Real ‘Brooklyn Style’ Cannoli Recipe,” which went on for nearly a year, finally concluded that, what distinguishes Brooklyn style cannoli created by shops such as Villabate, Alba, and Court Street Pastry, is a combination of nutmeg oil and cinnamon oil, corroborating Veniero’s recipe, and importantly, setting another distinguishing element between cannoli made in Italy and cannoli made in the United States.

In addition to the people I consulted at Ferrara and Veniero, I spoke with a number of Italian Americans about their cannoli recipes and cannoli customs, and all—reminiscent of Pitré’s observations from Sicily in the late 19th century—reacted with great pleasure at the mention of cannoli.

Eleanor Robertozzi is a 75 year-old Italian American of Neapolitan decent who lives in Elizabeth, NJ. Her recipe is as follows:

Shell: Flour (3 cups), sugar (1/4 cup), butter (3 TBSP), cinnamon (1 tsp), white wine (2 TBSP), and water (2 TBSP).

Mix all ingredients in a bowl adding water to the mixture a little at a time until it becomes a sticky dough. Knead into dough. Leave it to rest in the refrigerator for one hour before rolling it into thin sheets with flour and a rolling pin. Cut the dough into circles using a round bowl or dish. Wrap the cut dough around the steel cylinders, sealing its ends with egg white. Fry the dough cylinders in vegetable oil for 3-4 minutes. Remove, and let cool.

Cream: Cow milk ricotta, mascarpone cheese, confectioner’s sugar, vanilla extract, chocolate chips.

Mix the ricotta, mascarpone, sugar, and vanilla. Sieve the mixture overnight in the refrigerator using cheese cloth and a fine colander to drain the liquid out of it. Before serving, mix in chocolate pieces.

Preparation: After filling the shells with the cream, decorate the ends with candied fruit and powder with confectioner’s sugar.

Comments: Eleanor explained that because the cow milk ricotta she purchases at the supermarket is moist (Often mass-produced brands such as Polly-O or Sorrento brands are often the only kinds American home cooks have access to.), she adds mascarpone cheese. She said some other home cooks she knows add whipped cream. (Note: These additional ingredients corroborated my mother’s recollection about cannoli we purchased in Rhode Island where my family lived in the 1980s. My father, who is a first-generation Sicilian American who grew up in Graves End, Brooklyn and fondly recalls cannoli from Cuccio’s Bakery on Avenue X, could never accept cannoli from Providence’s Federal Hill shops. They were not true cannoli according to him. Perhaps because in addition to the absence of the New York style nutmeg oil-cinnamon oil combination, a principle reason was because of the cheese: one baker, who my mother asked, told her that he used mascarpone cheese in his recipe. )

Eleanor, like other Italian Americans I interviewed, including Dr. Joseph V. Scelsa, Founder and President of the Italian American Museum and Giovanna Bellia La Marca, author of Sicilian Feasts (New York: Hippocrene Books, 2004) and teacher of Sicilian cuisine at New York’s Institute of Culinary Education, supported Eleanor Robertozzi’s comments about ricotta—or “regotta,” as Dr. Scelsa wrote in an email—the fresher the ricotta, the better for the recipe.

Bellia La Marca, whose specialty is cassata Siciliana, which requires the same type of ricotta as cannoli, exclusively uses Calabro’s ricotta cheese that she purchases from Calandra Cheese Shop on Arthur Avenue in the Bronx to achieve the results she expects.

Pasticceria Bruno, which has three locations—two in Staten Island and its flagship on LaGuardia Place in New York’s Greenwich Village, is the award winning shop of pastry-chef-owner Biagio Settepani.

Settepani was born outside of Palermo, but as a teenager in 1973 he immigrated with his family to the United States. Now

in his 50s, he initially learned the art of pastry making from his aunt and mother at home. As a young man he served as an apprentice in a Neapolitan bakery in New York, and as an adult he studied at the “best schools specializing in pastry.”[x]

Settepani explained that when he first took over Pasticceria Bruno that he employed a traditional Sicilian cannoli recipe that included sheep milk impastata ricotta. But what he found was that in New York, Americans were not accustomed to the taste of the sheep milk. “It has a pungent flavor that they didn’t like,” he said.

To satisfy his customers, Settepani modified his cream recipe to include cow milk impastata ricotta, which he obtains from Calabro’s World of Cheeses like Ferrara and chef Bellia La Marca. But he did not stop there. “My wife is from Agrigento, Sicily,” he said. “In Agrigento, they have cannoli, but the cream is completely different than what I grew up knowing in Palermo.”

Settepani explained that in the ancient southern Sicilian coastal city, the cream they enjoy in cannoli shells is biancomangiare, a pudding that is made with a combination of milk, cornstarch, sugar and other flavors chosen by the chef such as almond extract or lemon or orange extract. Fascinated by this distinct difference from what he grew up knowing, Settepani experimented. He eventually settled on a cannoli cream recipe that includes a carefully balanced combination of cow milk impastata ricotta and biancomangiare along with more traditional ingredients such as vanilla and just the right amount of cinnamon: a recipe that has won him international accolades, but most importantly, has made is shops in New York City a huge success.

In the Greenwich Village location of Pasticceria Bruno, no completed cannoli were on display in the case, however, there were empty miniature and regular sized shells in plastic storage containers on the shelf behind the counter. True to what most cannoli connoisseurs prefer: at Pasticceria Bruno, they fill the cannoli when they are ordered.

In terms of consumption customs, we are no longer—both in Italy and in the United States—limited to eating cannoli during the cold months of the year or for a few festive occasions. Cannoli are enjoyed all year long thanks to modern refrigeration techniques. The cashier at Bruno said that people eat cannoli all year, and especially on major holidays such as Christmas, New Year’s, and Easter. Furthermore, new Americans from Sicily like Giusto Priola of Cacio e Vino, and Gennaro Picone of Gennaro restaurant rely on high-speed transportation to obtain coveted sheep milk impastata ricotta from Sicily.

My cousin Giuseppe D’Asta, the son of two Sicilians who emigrated to Varese during the 1960s, is a 30-year-old software consultant for Oracle. He lives in Varese, Lombardy, and recently wrote the following to me in a Skype message,

“A Varese ci sono due pasticcerie Siciliane, ma al nord, non ho mai mangiato i cannoli perché la ricotta non è buona come in Sicilia… quando ero un bambino (e anche ora) li ho sempre mangiati! Buonissimi! [Faccina] Di solito li mangiamo quando siamo in Sicilia in estate. Non c’è un momento particolare.”

(“In Varese there are two Sicilian pastry shops, but in the north [of Italy], I haven’t ever eaten cannoli because the ricotta isn’t good like in Sicily… When I was a boy (and still now), I always ate them there! So good! [Smiley Face] Usually, we eat them when we are there in the summer. There isn’t a particular occasion.”)

Giuseppe D’Asta, although just a consumer, understands the importance of the ricotta as the central element to a successfully executed cannolo.

In conclusion, one can analyze the different wines used in the dough recipe. Is it dry white wine or sweet Marsala? Or even

port wine, as Bostonian Marguerite DiMano Buonopane author of The North End Italian Cookbook (Old Sybrook: The Globe Pequot Press, 1997) suggests, or Limoncello as Mario Batali adds in his Epicurious video demonstration? Or just simply wine vinegar? Does one add cocoa or espresso to his dough recipe? Furthermore, do you need a particular ingredient like jasmine extract or candied pumpkin to make a spectacular cream? Preference for these ingredients depends on the chef and is not so dependent upon whether he or she is a true blooded Italian or Italian American. What distinctly defines a modern Italian cannolo from an Italian American one is whether or not it employs sheep milk ricotta or cow milk ricotta.

Italians/Sicilians go out of their way to use sheep milk ricotta, while Italian Americans have traditionally used cow milk ricotta, because until recently, there was no other option and, as proven by Biagio Settepani’s experience at Pasticerria Bruno, after over a hundred years of this tradition, Americans expect the flavor created by cow milk ricotta.

Like many recipes of Italian immigrants to the United States, cannoli recipes had to be modified to accommodate the ingredients available. What grew out of that necessity is a different tradition closely linked to its parent at home.

Needless to say, however, is that regardless of the different recipes, the centuries old tradition of cannoli continues, because as the ancient, debaucherous worshipers of Dionysus, and the nobles and the peasants of 19th century Palermo knew, and as Italian immigrants to the United States proved with their persistence—Lovely cannoli, nothing better in the world.

[i] Giuseppe Pitré, Usi e Costume, Credenze e Pregiudizi del Popolo Siciliano, Vol. 1. (Rome: Casa Editore del Libro Italiano, 1885).

[ii] Salvatore Farina, Sweet Sensations of Sicily. (Caltanissetta: Lussografica, 2009), 43.

[iii] Fabio Parasecoli, Food Culture in Italy. (Westport: Greenwood Press, 2004) 173.

[iv] Farina, Sweet Sensations, 39.

[v] Farina, Sweet Sensations, 42.

[vi] Farina, Sweet Sensations, 43.

[vii] Cherida V. Bush, Trans., Treasures of Sicilian Cuisine. (Palermo: PS Advert, 2004), 103.

[viii] Farina, Sweet Sensations, 26.

[ix] Giulinao Bugialli, Foods of Sicily & Sardinia and the Smaller Islands. (New York: Rizzoli, 1996), 271.

[x] Farina, Sweet Sensations, 146.

Allison Scola is Director of Communications at Columbia University School of General Studies and a professional musician with a great passion for Italian, Sicilian, and Italian American culture.

6 Comments

Wow! I will never have a question about cannoli again! Just had one from Modern Pastry in Boston…yummy! Sheep/cow, Ricotta/Marscapone. Ultimately authenticity gives way to taste.

This article was awesome!!! Really enjoyed the historical perspective, and the photos were great!!! Makes me want to get busy baking…and eating!!! Claire Walsh

A thoroughly researched article, down to the last detail. Let the taste-testing begin!

Allison, thanks for sharing your knowledge! This is so interesting.

Pingback: Thank You For A Fabulous 2012! | The Inquisitive Eater

Pingback: Cannoli’s Around Town | Life Between Meals