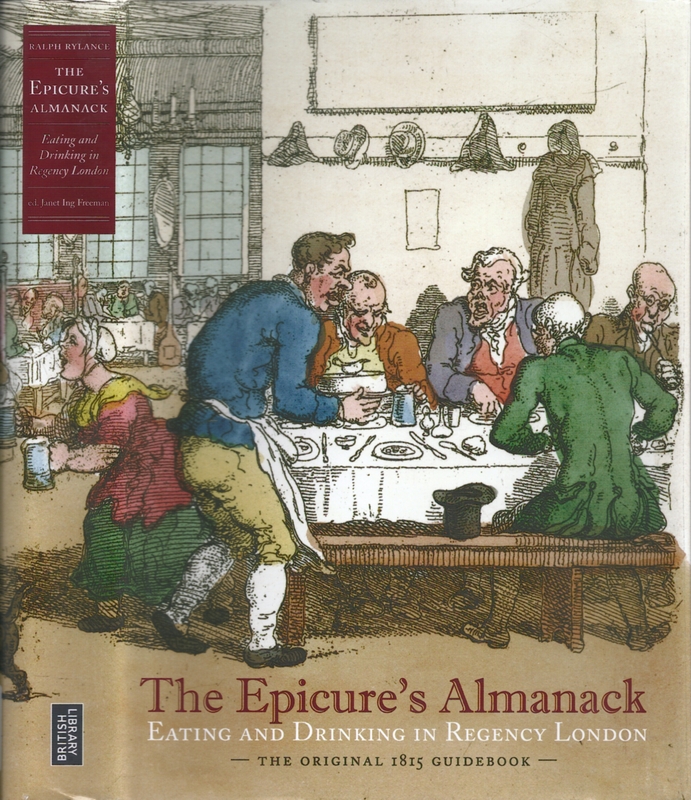

Book Review: The Epicure’s Almanack: Eating and Drinking in Regency London

by Larissa Zimberoff

Your dream, if you’re a book out of print, is that some benevolent author discovers you and brings you back to life.  The Epicure’s Almanack: Eating and Drinking in Regency London is just that book. And Janet Ing Freeman is just that fairy god author. As an example of some of the earliest guidebooks from its time, The Epicure’s Almanack (yelp before it was yelp) was first published in 1815.

The Epicure’s Almanack: Eating and Drinking in Regency London is just that book. And Janet Ing Freeman is just that fairy god author. As an example of some of the earliest guidebooks from its time, The Epicure’s Almanack (yelp before it was yelp) was first published in 1815.

Ralph Rylance, the author of this guidebook, was working as a freelance reader, translator, indexer and editor, when he was contacted by a local publisher who had just produced a popular guidebook, The Picture of London, which aimed at the curiosities in and near London. Rylance was engaged to produce a companion piece to The Picture that focused solely on food, drink and lodging.

It took Rylance almost two years to finish the book and when it finally came out, the publisher spent thirty guineas to advertise its arrival. Despite the financial support, the book was deemed a failure when, after almost two years, it had sold fewer than three hundred copies. The remaining print run was pulped and Rylance went back to freelancing. Flash forward almost two hundred years and you can now read an early example of dining reviews.

And this is where the book might be at its most helpful: to provide a historic snapshot of how society once looked upon dining out. Rylance touches on all the things we still care about: atmosphere, quality of food, and cost, but all in a much lighter tone and in significantly less detail than often seen in current reviews. It lacks the detail we dive into today when we talk about food; the minutiae of the meal we had last night and share with friends on our social network of choice.

The reviews stick mostly to eating houses, taverns and, to a lesser extent, coffee houses, in the environs of London and its outskirts. In this updated version, Janet Ing Freeman maintains the contents of Rylances’ almanack almost untouched. Freeman restricts her role to adding footnotes, providing the new reader with additional history to the contemporary establishments. This guidebook guides no more but what it does do is give us a taste of the culture and language of the early 1800’s.

Reading the descriptions of food is perhaps the most fun of flipping through the pages of this book, exemplified by Crish’s A-la-mode Beef Shop, where “a stranger may venture to stay his stomach without fear of being haunted by the horrible doubt as to whether the animal whose corps he is feasting on was, when alive, an inhabitant of the stall or the stable.” Rylance earnestly tells us of Dolly’s Chop House, in Queen’s Head Passage, where “orders are sometimes executed with commendable promptitude.” And the atmosphere? That’s covered too, like at the Horn Tavern on Godliman Street, where “joyful heirs and sad widows promiscuously meet to take their bodily nourishment.

Towards the end of the book we’re treated to reviews of many local markets as well as an alimentary calendar detailing the best times for food (beef and veal in January), a description of what it should look like (good beef should have a smooth open grain), or perhaps the gloomiest month of the year (November). I’m not quite sure what to do with this book now that I’ve flipped through it, but should I ever want to travel back in time, I’ll know exactly where I want to go first.

Edited by Janet Ing Freeman

Publisher, British Library

Larissa Zimberoff is a freelance writer living in Manhattan. She is currently working towards her MFA at The New School. Her writing has appeared in Salon, Untapped Cities and The Rumpus.