My final moments, I figure, will be just like in ‘Citizen Kane’: from the master bedroom of a decaying mansion stuffed with classical sculpture, I’ll stare longingly into some cheap Perzy snow-globe; as it drops from my limp fingers, a single word will fall from my lips. Only it won’t be ‘Rosebud’ but ‘Rarebit’, and some poor reporter will have to wade through centuries of culinary and linguistic history in order to decipher my meaning.

Welsh Rarebit is not the national dish of Wales – that honour goes to Cawl, a one-pot stew made mostly from leak, lamb, and (strangely enough) potatoes; but Rarebit is the favourite child. In its essential form, it simply consists of melted cheese on a slice of toast – though there are many variations on the theme. And like most British food, Welsh Rarebit is largely flavourless – or, at least its flavours are exceedingly simple. But to criticise it on these grounds is to miss the point entirely: you might as well accuse a painting of being unmusical. British food is not defined by taste, but by texture: the airy/crispy batter of Yorkshire puddings; the chewy/chalky crust on Melton Mowbray porkpies – not to mention the greasy/rubbery/gooey filling within. And Welsh Rarebit is no exception. Its appeal lies in the collision of the crunchiness of a well-toasted piece of bread and the ooziness of melted cheese – the dryness of the one providing the total opposite, and yet the perfect complement, to the semi-liquidity of the other. For which reason, Welsh Rarebit must always be served hot: you cannot make it one day and serve it the next, or else the magic is lost. Why would you anyway, when it takes only minutes to prepare fresh?

My final-moments-fantasy might not be as far-fetched as it sounds. Welsh Rarebit was the favourite meal of William Randolph Hearst – the real-life newspaper mogul on whom Orson Welles based Charles Foster Kane. In The Enchanted Hill Cookbook (1985)– a collection of recipes assembled by the staff of Randolph Castle – Hearst’s son recalled his father’s cooking habits:

lunch would be about 1:30pm, dinner about 8:30 or 9pm, followed by a movie, and if the night would run, as it frequently did, for an hour or so later, the chances were better that even he would be in the kitchen either grabbing a snack of cold meat and cheese for himself, or making a Welsh rarebit for all comers. The latter dish he made with pride and some beer, but whatever the recipe, I know it was a favourite of all those who were fortunate enough to partake of it.

If this seems odd – if the simplicity of Welsh Rarebit feels out of place in the Castle’s lavish dining hall (whose fifty-four foot table, forty upholstered chairs, tapestries, pennants, and guidons, served as the inspiration for Hogwarts’) – let’s not forgot that the napkins there were made of paper, nor that the sauces were served straight from the manufacturers’ bottles. ‘This’, explained Alexander Theroux in Einstein’s Beets (2017),

was not an economizing feature, but rather a sentimental one. Such informalities reminded the very sentimental Hearst of the early days of the 1870s and 1880s when he came out to this very spot with his mother and father where they picnicked in the open. These were detailed memorials and reminders of his youth.

It was this same sentimentality which Welles sought to capture in ‘Citizen Kane’: ‘Rosebud’, it famously transpires, is the name of the snow-sled which Kane played on as a child – that is, before his bank-appointed guardian began grooming him for life as an American oligarch. Kane’s dying breath, then, is a reminder of the homely comforts denied him in this life and longed for in the next. Did the flesh-and-bone Hearst taste that same reminder in Rarebit?

I do, anyway. Because I grew up in Wales, I was raised on the stuff. I ate it with my mother on weekends and I ate it with my grandmother during the school holidays. I ate it in cafes and, on special occasions, restaurants. Most of all I ate it with Mrs Jones, who minded me at her home after school, and whose culinary repertoire included just two dishes: the first was the bacon butty – another British staple, also unfairly maligned as flavourless (again, flavour is not the point: the butty gains its appeal from the interplay between the dry/elastic white bread roll and the greasy/crunchy half-burnt bacon tucked inside); and the second was Welsh rarebit. I don’t live in Wales anymore, and I haven’t seen Mrs Jones in twenty years, but Rarebit is still – perhaps, especially now – my home-away-from-home, the familiarity that I yearn for when everything around me feels foreign and nightmarish. But Welsh Rarebit, I contend, has something about it which makes even non-Welsh feel homesick for it – something which its doppelganger, Cheese on Toast, does not.

The first written reference to ‘Welsh Rarebit’ occurs in Hannah Glasse’s The Art of Cookery (1747), where a version of the dish (with mustard) is listed between ‘Scotch Rarebit’ (without mustard) and ‘English Rarebit’ (with wine). But this is a misleading start: ‘Scotch’ and ‘English’ Rarebit don’t appear in earlier cookbooks, and are doubtless just inventions of Glasse’s own; nor is Welsh Rarebit one of several variations on some Ur-Rarebit – Welsh Rarebit is the Ur-Rarebit. And its actual origins lie in a South-Valley version of Caws Pobi(roasted cheese) – one served on bread, and requiring the cheese to be mixed with milk and eggs prior to roasting (under the heat, the cheese softens, the milk steams, and the eggs harden, simultaneously). At some point, someone had the good sense to omit the milk and eggs. ‘Welsh Rabbit’ was the name which the English gave to the result, and it was first written down in 1725 by the poet John Byrom, who wrote in his diary that year:

– Sunday, April 4th: I did not eat of the cold beef, but of Welsh rabbit and stewed cheese […].

– Tuesday, April 6th: I had a scallop shell and Welsh rabbit. […]

– Saturday, May 15th: We had cold veal, a bottle of mountain, I ate rather too heartily of the veal and a Welsh rabbit.

‘Welsh Rarebit’, in other words, is simply a corruption of ‘Welsh Rabbit’ – probably Glasse’s attempt to clear up the confusion inherent in the fact that the dish doesn’t contain any rabbit. So why ‘Rabbit’ in the first place?

A good answer was yielded by Abram Smyth Palmer’s Folk Etymology: a Dictionary of Verbal Corruptions or Words Perverted in Form or Meaning by False Derivation or Mistaken Analogy (1882):

The phrase [Welsh Rabbit] is one of a numerous class of slang expressions – the mock-heroics of the eating-house – in which some common dish or product for which any place or people has a special reputation is called by the name of some more dainty article of food which it is supposed to supersede or equal. Thus a sheep’s head stewed with onions, a dish much affected by the German sugar bakers in the East End of London, is called a German Duck.

‘Welsh Rabbit’, then – like Severn Capon (sole), Yarmouth Capon (red herring), Poor Man’s Goose (liver and potato stew), Weaver’s Beef (sprats), Cape Cod Turkey (codfish), Albany Beef (sturgeon), or Bombay Duck (bummalo fish) – is simply ironic, a dish named after a delicacy which it patently isn’t. But why ‘Welsh’? How does the inclusion of that awkward designation cause ‘Welsh Rabbit’ to mean something like ‘Not Actual Rabbit’?

I say awkward because the Welsh don’t call themselves ‘Welsh’, nor any cognate of that term – at least, not when they’re speaking Welsh (which they don’t call ‘Welsh’ either); they call themselves Cymro (sg) or Cymru (pl), and their language Cymraeg – words which descend from ‘kömroɣ’, a (reconstructed) term from late proto-Brythonic meaning something like ‘compatriot’ or ‘fellow-countryman’. Conversely, ‘Wales’ and ‘Welsh’ descend from ‘Walhaz’, a (reconstructed) term from proto-Germanic which descends, in turn, from the name of the tribe known to the Romans (from the writings of Julius Caesar) as the Volcae, and to the Greeks (from those of Strabo and Ptolemy) as Οὐόλκαι. But the speakers of proto-Germanic didn’t really care to distinguish among their neighbours in the South, and applied the term indiscriminately to the inhabitants of all Celtic lands which had been assimilated by the Roman Empire. Hence, ‘Welsh’ and its cognates often bear connotations of ‘non-native’ and ‘foreign’, ‘weird’ and ‘strange’. In Swiss-German, for example, ‘Welsche’ is a pejorative used to describe Swiss speakers of Italian and French; in Polish, ‘Włochy’ is a mild slander towards Vlachs and Romanians. Hence, the English term ‘Welsh Rabbit’ might be understood as something approximating ‘Weird Meat’ – a strange beast consumed by a strange people. But what kind of ‘strange’ are we talking about here?

Beside its own recipe for ‘Welsh Rarebit’ (with milk, mustard, and Worcester sauce), the 1950 edition of The Betty Crocker Cookbook cites a law forbidding the Welsh from eating rabbits caught on the estates of the (English) nobility: unable to hunt the real thing, the Welsh simply melted cheese instead. Here, ‘Welsh Rabbit’ might mean something like ‘the Welsh substitute for the game denied them’. But not just any substitute, mind: ‘Welsh’ has long been used by the English to refer, specifically, to pooror inferior versions. In Francis Grose’s A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue (2nd ed. 1788), for example, we find the following entries:

Welch comb: the thumb and four fingers.

Welch fiddle: The itch

Instead of combing their hair, the Welsh just run their hands through their mangy locks; instead of plucking dulcet tones from the violin, the Welsh just scratch their skin; and instead of tucking into a well-stewed rabbit, the Welsh just gnaw on hunks of cheese. On top of this, an old English stereotype holds the Welsh to be a nation of lying schemers; hence, ‘Welsh’ might further connote an inferior substitute which has been fobbed off as the genuine article. But a question remains: why was the phrase applied to a version of Caws Pobi? Surely these landless weirdos weren’t ever cunning enough to get away with serving melted cheese in place of actual rabbit?

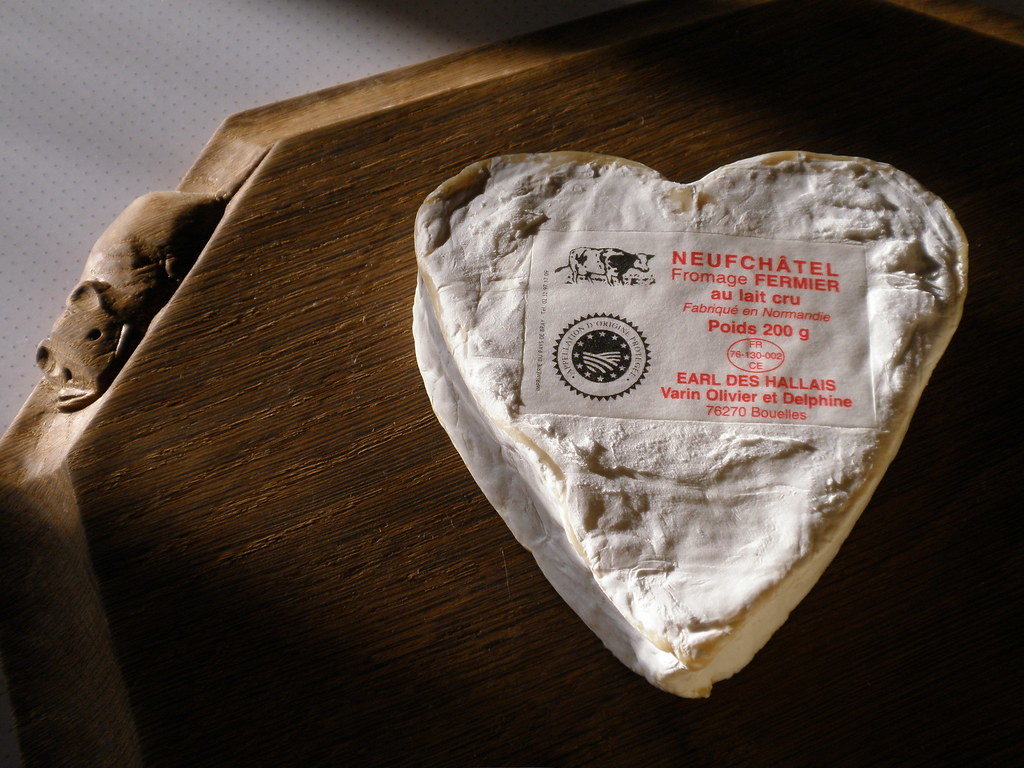

Another old English stereotype holds the Welsh to be excessively fond of cheese. On one hand, this doubtless stems from the fact that Wales, from time immemorial, has been a prolific producer of dairy. But what’s interesting, in this respect, is that traditional Welsh cheeses wouldn’t have been very good in Rarebit. Because of the acidic soils in Wales, the milk from its cattle tends to produce soft varieties, and these don’t melt very well; to make Caws Pobi, early Welsh would have had to trade with their neighbours for harder types like Cheddar. On the other hand, calling a dish of melted cheese ‘Welsh Rabbit’ is a joke at the expense of Welsh poverty: well before it became the mark of the gourmand, cheese was synonymous with a cheap fill. Hence, also in Grose, we find the following:

Welch Rabbit: Bread and cheese toasted…The Welch are said to be so remarkably fond of cheese, that in cases of difficulty their midwives apply a piece of toasted cheese to the janua vita to attract and entice the young Taffy, who on smelling it makes most vigorous efforts to come forth.

‘[J]anua vita’ is Latin for ‘the gates of life’ – a euphemism for the vagina; and ‘Taffy’ is a (still extant) slang term for a Welsh person – either an anglicisation of the name Dafydd, or a reference to the South-Welsh river Afon Taf. Here, cheese is not just a cunning substitute for rabbit; it is one whose cheapness makes it more attractive to the Welsh than actual rabbit. Welles (who once dismissed ‘Kane’as ‘dollar-book Freud’) used to annoy Hearst by publicly joking that ‘Rosebud’ was the tycoon’s nickname for his wife’s ‘janua vita’; for the bargain-crazy ‘Taffy’, Rarebit would exceed whatever comfort might have been found there.

In fact, the stereotype of the Welsh as excessively fond of cheese runs much deeper than Grose. In A C Merrie Tales (1526), we find the following explanation for why there are no Welsh in heaven:

I fynde wrytten amonge olde gestes, howe God mayde Saynt Peter porter of heuen, and that God of hys goodnes, sone after his passyon, suffered many men to come to the kyngdome of Heuen with small deseruynge; at whiche tyme there was in heuen a great company of Welchemen, whyche with their crakynge and babelynge troubled all the other. Wherfore God sayde to saynte Peter, that he was wery of them, and that he wolde fayne haue them out of heuen. To whome saynte Peter sayd: Good Lorde, I warrente you, that shal be done. Wherfore saynt Peter wente out of heuen gates and cryed wyth a loud voyce Cause bobe, that is as moche to saye as rosted chese, whiche thynge the Welchemen herynge, ranne out of Heuen a great pace. And when Saynt Peter sawe them all out, he sodenly wente into Heuen, and locked the dore, and so sparred all the Welchemen out.

For the Welsh, the comforts of Caws Pobi exceed those enclosed not only within the gates of life, but within the gates of paradise. Their fondness is not merely senseless but altogether ungodly.

But madness for cheese is only one of a number tropes via which the Welsh have been depicted as an unreasonable people. Elsewhere in English letters, we find Welsh characters speaking gobbledegook, obsessing over quack-astrology, being prone to inexplicable bouts of violence, and getting caught up in circular dialogues and false logic (that is, when we are not busy with our cunning schemes). Fondness for cheese might well be another item on this list, another instance of the same godless irrationality, but it might also be the source: cheese has long been held by folk wisdom to give its eaters crazy dreams. What’s more, there might be something in this. In 2005, the British Cheese Board conducted a weeklong study in which participants ate 20 grams of cheese half an hour before going to bed each night. Each participant was assigned one of seven types of cheese: Stilton, Cheddar, Red Leicester, Brie, Lancashire, or Cheshire. And of those who ate Red Leicester, 83% recorded pleasant dreams, of which 60% were of fond childhood memories (Cheddar often produced dreams about celebrities, while Cheshire usually produced no dreams). But what if you don’t want ‘pleasant’ dreams? What if you want ‘strange’ or ‘Walhaz’ visions?

Then – according to Literature, at least – you must eat Welsh Rarebit. In Edgar Allan Poe’s ‘Some Words with a Mummy’ (1845), the narrator manages to resuscitate an Egyptian mummy – before engaging it in a conversation about theology, technology, and cough drops; in H.G. Well’s ‘The Man Who Could Work Miracles’ (1898), the protagonist discovers that he is a wizard with unlimited powers – only, he does not inhabit some faraway fantasyland but the familiar streets of suburban London. Both stories begin with characters helping themselves to copious amounts of Welsh Rarebit, and in both stories, Welsh Rarebit functions as a narrative clue, as the sign that everything might have been a dream all along. The understanding here is twofold: first, Welsh Rarebit doesn’t just give us ‘pleasant’ dreams; second, it doesn’t just give us straightforward nightmares either. In a Rarebit dream, Ancient Mummies talk like ordinary people, and regular Londoners turn out to be sorcerers. In a Rarebit dream, things are properly strange – which is to say, strangely normal.

The difference between Welsh Rarebit and Cheese on Toast, then, is one of ontology. The latter can be positively defined, its existence delineated via recourse to the ingredients actually present in the dish: namely, cheese and toast. For this reason, if you add anything to Cheese on Toast it ceases to be Cheese on Toast, and becomes, say, Cheese and Onions on Toast, or Cheese and Bacon on Toast. Welsh Rarebit (like everything in Wales) has a more ghostly existence, is defined by its shadows, by what is absent: on the one hand, actual rabbit; on the other, Fundamental English Values (or at least, the Values which the English consider Fundamental to their self-identity): moderation, discernment, rationality, godliness, and a hard and fast distinction between native and foreign. This is why you can add anything (except, of course, for actual rabbit) to Welsh Rarebit – beer, mustard, Worcester sauce – and still have Welsh Rarebit. It’s also what makes so many non-Welsh feel legitimately homesick for its comforts: the dish itself is an uncanny violation of the prescribed distinctions between homely and foreign, familiar and ‘Walhaz’.

And few have known this better than the great American cartoonist Winsor McCay. On September 10, 1904, McCay began his magnum opus: a comic strip called ‘Dream of the Rarebit Fiend.’ It had no continuity, only a recurring formula: characters would eat Welsh Rarebit before going to bed, and the strip would depict their dreams. Again, these were neither ‘pleasant’ visions, nor straightforward nightmares, but something in between: flying cottages, oversized neighbours, and domestic pests swollen to grotesque proportions. But the most influential of McCay’s visions were his images of giant creatures attacking American metropolises – the precursors to the ‘King Kong’ franchise, and to the entire genre of Japanese monsters known as 怪獣 Kaiju, or ‘Strange Beast’. What made those creatures properly strange? When King Kong ravages a familiar city like New York City, it’s not immediately clear who the monster is. The giant ape from faraway? Or the city which shipped him out in chains and forced him to entertain its elite? In all good Kaiju films, the monster is weirdly familiar, the familiar uncomfortably monstrous. Perhaps it’s a coincidence that their origins lie in ‘Welsh Rabbit’ – the strangest beast of all. Perhaps it’s also a coincidence that McCay was employed – and employed very handsomely – by William Randolph Hearst.

The difference between Welsh Rarebit and Cheese on Toast, then, is one of ontology. The latter can be positively defined, its existence delineated via recourse to the ingredients actually present in the dish: namely, cheese and toast. For this reason, if you add anything to Cheese on Toast it ceases to be Cheese on Toast, and becomes, say, Cheese and Onions on Toast, or Cheese and Bacon on Toast. Welsh Rarebit (like everything in Wales) has a more ghostly existence, is defined by its shadows, by what is absent: on the one hand, actual rabbit; on the other, Fundamental English Values (or at least, the Values which the English consider Fundamental to their self-identity): moderation, discernment, rationality, godliness, and a hard and fast distinction between native and foreign. This is why you can add anything (except, of course, for actual rabbit) to Welsh Rarebit – beer, mustard, Worcester sauce – and still have Welsh Rarebit. It’s also what makes so many non-Welsh feel legitimately homesick for its comforts: the dish itself is an uncanny violation of the prescribed distinctions between homely and foreign, familiar and ‘Walhaz’.

And few have known this better than the great American cartoonist Winsor McCay. On September 10, 1904, McCay began his magnum opus: a comic strip called ‘Dream of the Rarebit Fiend.’ It had no continuity, only a recurring formula: characters would eat Welsh Rarebit before going to bed, and the strip would depict their dreams. Again, these were neither ‘pleasant’ visions, nor straightforward nightmares, but something in between: flying cottages, oversized neighbours, and domestic pests swollen to grotesque proportions. But the most influential of McCay’s visions were his images of giant creatures attacking American metropolises – the precursors to the ‘King Kong’ franchise, and to the entire genre of Japanese monsters known as 怪獣 Kaiju, or ‘Strange Beast’. What made those creatures properly strange? When King Kong ravages a familiar city like New York City, it’s not immediately clear who the monster is. The giant ape from faraway? Or the city which shipped him out in chains and forced him to entertain its elite? In all good Kaiju films, the monster is weirdly familiar, the familiar uncomfortably monstrous. Perhaps it’s a coincidence that their origins lie in ‘Welsh Rabbit’ – the strangest beast of all. Perhaps it’s also a coincidence that McCay was employed – and employed very handsomely – by William Randolph Hearst.

Oscar Mardell was born in London and raised in South Wales. He currently lives in Auckland, New Zealand, where he teaches Classics, brews beer, and practices Aikido. His poetry and essays have appeared in a variety of publications, including War, Literature & the Arts, The Literary London Journal, 3:AM Magazine, DIAGRAM, Terse, and Queen Mob’s Teahouse. He is the author of Rex Tremendae from Greying Ghost and Housing Haunted Housing from Death of Workers Whilst Building Skyscrapers.