by Fabio Parasecoli

1971, the year when Alice Waters opened Chez Panisse in Berkeley, CA, is often cited as a turning point for American cuisine. The young woman, who had lived in France while pursuing her degree in cultural studies, had discovered the pleasure of shopping for fresh, local produce, and a relaxed yet creative way of preparing and serving food. What’s more important, she had found a way to translate those values in an American context.

Yet, something else had been stirring in France, something that would have an equally crucial impact on the development of the culinary arts in the U.S. Just before Waters’ visit in the winter of 1970, some Cialis vs viagra of the most visible and influential innovators in the American food world happened to cross paths in Provence. James Beard, Julia Child and her co-author Simone Beck, M.F.K Fisher, Richard Olney, and culinary book editor Judith Jones found themselves dining together and visiting with each other while discussing their past work and their future projects.

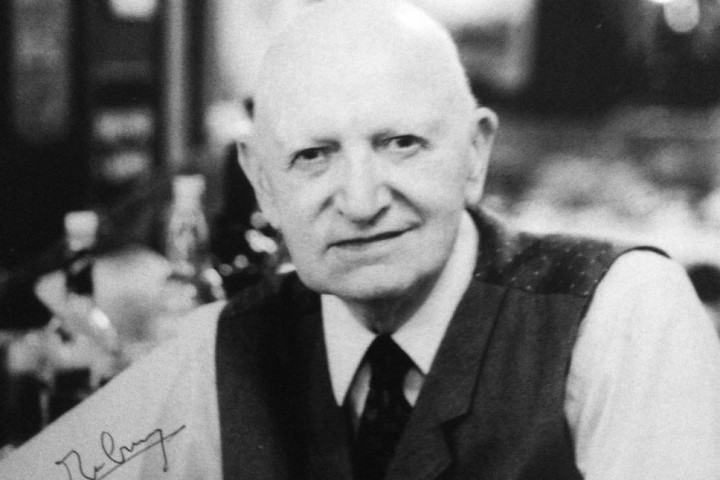

This is the story that Luke Barr, whose great-aunt was M.F.K. Fisher, tells with gusto in his book, Provence, 1970: M.F.K. Fisher, Julia Child, James Beard, and the Reinvention of American Taste. Barr’s narrative follows the movements and gatherings of these iconic figures, revealing their confidences, their tensions, and even some of their less lofty moments. Beard, Child, and Fisher are described in all their humanity, in a tone that avoids the hagiographic quality that is used regularly in celebrating their achievements. Much of the information that Barr includes in the story comes from Fisher’s diary that he found in a storage unit where her family members had stored and forgotten it. The diary chronicles the final weeks of 1970, when Fisher was in Provence with her famous friends and then traveled by herself trying to evaluate France more objectively and to rethink the role that country had played in her imagination up to that point. The diary is an important document, which, when read with Beard’s, Child’s, and Fisher’s already known letters, allow Barr to give readers access to an important slice of American culinary history.

According to Barr, Fisher’s personal reflections and resolutions intriguingly reflect important changes in the attitudes and outlooks of the other culinary giants she interacted with in Provence. James Beard was trying to finish American Cookery, an important book that was meant to assert the value and relevance of American cuisine without any sense of cultural or material subordination to foreign traditions. Julia Child, who had introduced French cuisine to the general public in the U.S. through her writing and TV show, had been able to make everyday cooks feel comfortable with complicated recipes and exotic ingredients. At the same time, she felt it was time reclaim a certain freedom from the strictures of total obedience to the French tradition. She was also fully aware that many elements given for granted among French cooks had to be explained and broken down in layman’s terms for many of her readers this side of the Atlantic.

Barr suggests that Beard and Child’s pragmatic approach put them at odds with Simone Beck, who was proud of the uncompromising “Frenchness” of her food and considered Julia less strict when it came to the requirements of serious cooking, and with Richard Olney, a relative newcomer in the field of culinary writing asserting himself as an unadulterated interpreter of the most authentic French food. Fisher herself realized that France was changing and many of the notions they were fondly attached to might have become anachronistic. At the same time, she had started to realize the changes in the American culinary scenes in terms of production, availability of ingredients, and social relevance of food.

With its focus on the media world, cultural perceptions, and the role of writers and intellectual mediators, Barr’s book helps us add another layer to our understanding of the dynamics that have made American food what it is now in terms of practices and ideas. The author comes back over and over again to some central concepts, as though making sure the readers get his point, but these repetitions aside, the book makes for a nice, relaxing reading, taking us back to a time and a place that still exerts a strong charm on many of us.

This article first appeared on the Huffington Post.

Fabio Parasecoli is an Associate Professor and Coordinator of Food Studies at the School of Undergraduate Studies for The New School for Public Engagement. He also a Senior Editor of The Inquisitive Eater, and regular contributor to The Huffington Post.