I grew up in a family obsessed with the tales and characters of Beatrix Potter. (I’ve conferred with my siblings, who confirm that obsessed is no exaggeration.) Our home, a farmhouse with a robust vegetable garden in the middle of an apple orchard, was conducive to relating to the Lake District landscapes of Potter’s illustrations. But also, my gardener-mother surrounded us with Potter paraphernalia: not just the adorable books—the deceptively fraught tales of Peter Rabbit et al—but also various representations of those characters: posters and figurines, dishware and linens, lamps and piggy banks. My mother’s current adorable pup is named for one of Peter’s sisters, Mopsy.

As a grown-up, I’ve retained a devotion to Potter’s world: Its mixture of tweedy country elegance and latent animal appetite has informed my poems and my wardrobe. Among other aspects, I am fascinated, amused, and troubled by the ways in which its world of decorum overlays the primal drives of its characters, including the urge to eat neighbors they otherwise cordially engage.

Predation among animals takes on a different flavor when those animals dress and behave in varying degrees like people. How Potter modulates this relationship is increasingly interesting to me, and I am eager to pull together some sentences about it .

I am less interested in Peter Rabbit, the character who has become synecdochal for Potter’s entire menagerie, than I am in some other figures. However, it is germane that when we first meet Peter, his mother has put him in a blue windbreaker and warned him not to get eaten by a nearby (human) farmer, a fate that had befallen Peter’s father. That Peter eventually loses his clothes and doesn’t get eaten foretells a curious and unsettling trend in Potter’s tales: when Potter’s animals venture forth in human costume, they run a greater risk of being devoured than if they remain (or eventually revert to being) naked and on all-fours. In other words, their outfits somehow call attention to their edibility, whether by human or animal neighbors.

Some of my favorite of Potter’s books emphasize this state of being scrumptiously attired. Published in 1906, The Tale of Jeremy Fisher begins with Jeremy, a dandy frog, lounging in a burgundy smoking jacket over a floral waistcoat, a cravat tied around his froggy non-neck, tight-fitting hosiery, brindled to match his particular dermatology, ending at the ankle, leaving a small but provocative gap above his pointy, tasseled shoes (which, to add to the watery, slithery ethos of the tale we might call moccasins).

In a certain parlance, to certain viewers, Jeremy looks good enough to eat. And, indeed, he is. He takes a lily pad out punting in order to fish and, in a terrifyingly illustrated moment, his leg dangling into the water in unsuspecting languor, is seized from beneath by a fearsome trout and dragged under. He would have been consumed if it had not been for his unpalatable mackintosh, which he’d put on, along with a pair of galoshes, due to the rainy weather: the trout spits him out, albeit separated from his outfit.

The idea of a posh frog may seem incongruous, even in Potter’s world of well-appointed, anthropomorphized critters, but I think it is indicative of her subtle wit and psychological insight: Jeremy, whose amphibiousness should render rainy-day gear unnecessary, nonetheless wears a rain coat and rain boots. This is characteristic of Potter in several ways. For one thing, her stories are set in the northwest of Victorian England, or at least a facsimile; it may be rustic, but it is still decorous. For another, Potter never lets us forget that who we are is what we put on—taxonomically and sartorially—and that putting on an outfit doesn’t exempt us from our role in the food chain. Quite the contrary, in fact.

Jeremy is far from the only Potter character whose human outfit doesn’t prevent others from trying to eat them—and in fact may make them more appetizing. In her eponymous tale, Jemima Puddle-Duck is perfectly safe while puttering naked in the barnyard with the chickens and horses. It’s only when she heads out into the world, first putting on a shawl and a poke bonnet like any respectable farmwife, that she falls prey to the charms and desires of Mr. Tod, “an elegantly dressed gentleman,”—a fox in all senses of the word. Dress in Potter’s tales frequently serves both to liberate and entrap: in this one, Jemima cannot leave the farm unless properly dressed, yet she naïvely succumbs to the allure of a fastidious predator in a good suit. What makes the tale particularly sadistic, I think, is how Mr. Tod draws out his seduction/abduction/consumption of Jemima. He doesn’t simply gobble her up, but sends her unwittingly back and forth to the farm to gather herbs and vegetables which he ultimately plans to use when he cooks her. (He tells her the ingredients are for an omelet, as if this should be any less distressing for an egg-laying mother-to-be, who left her farm in the first place to find a place to sit peacefully on her eggs until they hatched; the room lent to her by Mr. Tod for that purpose is suspiciously full of feathers.) In this, his treatment of Jemima is torturously and connivingly human, his conduct suggesting a duplicitous aspect of elegance not depicted by Jeremy Fisher, who simply falls prey to a non-personified natural predator.

The Tale of Jemima Puddle-Duck was written in the same period, and set on the same farm, of another of Potter’s books, The Tale of Tom Kitten. I relate to Tom Kitten—or maybe I envy him: He doesn’t care when he’s grown too plump for his nicer clothes, or if he tears them while climbing the rockery (the what?) or galivanting through ferns with his sisters, Mittens and Moppet. As they play, the kittens even run into Jemimah and the other Puddle-Ducks, Rebekah and Drake, and are tickled when Drake puts on Tom’s discarded clothes and parades around like a fancy–pants, exclaiming “It’s a very fine morning!” Somehow, though the kittens themselves were dressed in finery and walking on their hind legs, it is ludicrous to them when farm animals put on their clothing.

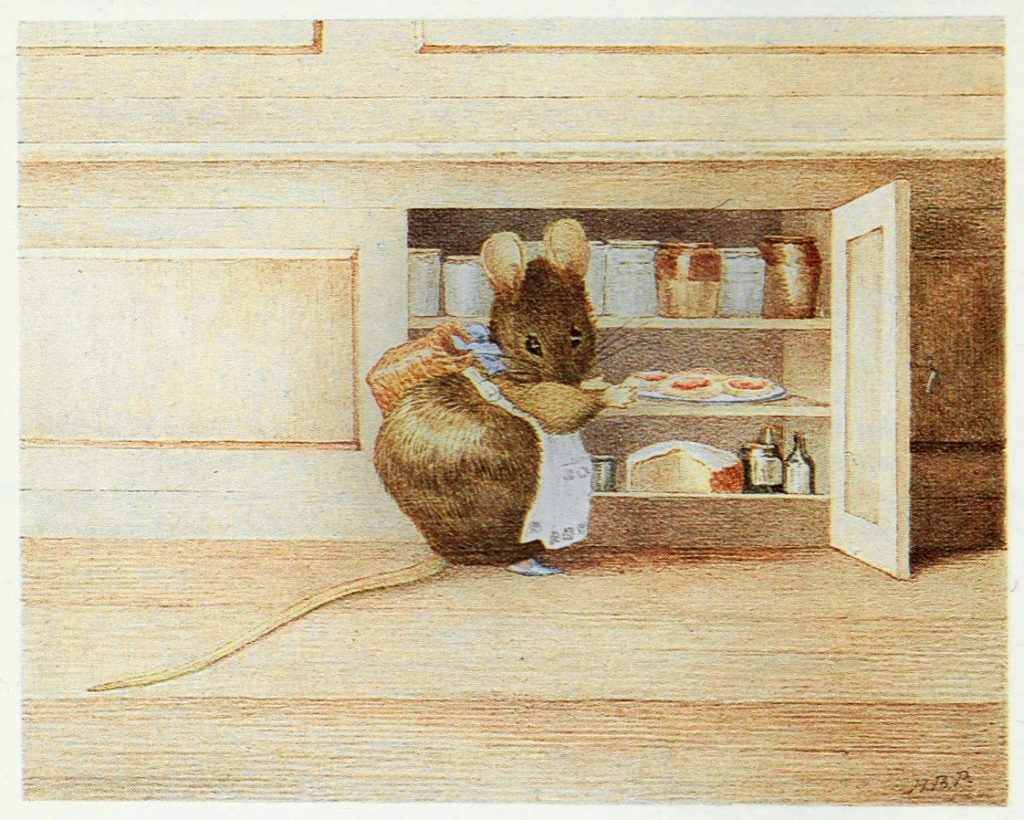

As in the world of Disney, not all animals in Potter’s books are equally anthropomorphized. And, as I mentioned, the more human the characters in Potter’s pantheon are meant to appear, the more edible they often become. Tom Kitten also appears in a sequel, The Roly-Poly Pudding, a terrifying book published in 1908 and retitled The Tale of Samuel Whiskers in 1926. Once again, disobedient Tom resists the efforts of his mother, Tabitha Twitchet, to make him presentable. He escapes up the chimney and finds his way beneath the attic floorboards, where he is captured by two enormous, thuggish, clothed rats: rotund Samuel Whiskers and his wiry wife, Anna Maria. The rats tie up sooty Tom, then smear him in butter and wrap him in dough in order to make a pudding of him. As in Jemima’s case, Tom’s abduction and separation from those who might help him is part of what makes the tale unsettling—but at least in the latter tale it makes sense that a fox would eat a duck, even if their shared human comportment gives it a whiff of cannibalism. But two rats overpowering and breading a young cat in order to bake and consume him seems considerably more perverse to me than even Mr. Tod’s fetishized duck-hunting. (Interestingly, in both tales, it’s domestic dogs—a pack of non-personified young hunting dogs in one case and a collie-carpenter in the other—who save the day, though not without some disheartening collateral damage in Jemima’s case.)

The tales of Jemima Puddle-Duck and Tom Kitten were my favorites of Potter’s books growing up; I was entranced by their creepy domesticity. Now, I have an additional favorite, The Tale of Pigling Bland, a wistful book that I barely knew or understood as a child. Published in 1913, it was one of the last of Potter’s original twenty-three tales to be written, which I think makes sense: similar to the earlier tales, it presents the mortal risk of being eaten if you put on clothes and go out into the world, but the story plays out differently: longer, sterner, and irrevocable (though not without a certain final hopefulness).

Like Peter Rabbit and Tom Kitten, Pigling Bland begins his story naked, safe, and quadrupedal—and at the trough with his many siblings, where they are fed from a pail by their clothed, bonneted, and upright Aunt Pettitoes. Like Peter and Tom, he is soon dressed handsomely and sent out into the world by his aunt…but not to play. Overwhelmed by her piglet charges, Pettitoes instructs the dutiful Pigling Bland to travel by foot to Lancashire to sell himself and his mercurial little brother, Alexander, at market—never to return to the family farm. “Mind your Sunday clothes and remember to blow your nose,” she tells the brothers. “Beware of traps, hen roosts, bacon and eggs; always walk upon your hind legs.”

I have always been distressed by this injunction, which I see as giving very conflicting advice: look respectable and avoid being trapped or eaten, but only so you can then sell yourself at market to someone who will entrap and eventually eat you. In his striped blue waistcoat and plum topcoat, Pigling Bland is like an epicurean menu item: worsted pork wrapped in gabardine. The effect is gruesome and, again, depraved, cannibalistic: What respectable mammal would devour such a respectable mammal? Of course, the underlying Dickensian message of Pigling Bland’s outing is among the most traumatic a child can receive: leave home immediately and never come back (but behave yourself in the process). How he is to ultimately perish is perhaps only narrative gravy.

Pigling Bland is a compliant young pig-man, and the tensions of his tale are more municipal than in other Potter stories. He and Alexander are given indispensable papers, licensing them to travel to market and sell themselves there. If they are caught without papers, they will be returned home by the police, which is in fact what eventually happens to Alexander—a poignant irony: the gluttonous, sticky, messy, distractible little brother cannot follow the rules, and so is escorted back to the comfort and safety of the farm, while his conscientious older brother journeys on toward his demise, alone and terrified. (It occurs to me, as an aside, that conventional disobedience, negligence, or boundary-pushing doesn’t usually have out-of-whack consequences in Potter’s tales, though mean-spiritedness doesn’t go unpunished— cf. The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin).

Lost, cold, and despondent, Pigling Bland takes ill-advised refuge in a hen house, where he is promptly found and abducted by a farmer, who takes him inside and, in a squirmy moment of alimentary dissonance, gives Pigling Bland porridge and a chair by the stove while consulting an almanac to assess whether it was too late in the year to make smoked ribs of him. There are additional, comparably unnerving moments that follow, which I plan to write about in a future, longer version of this essay.

Most of Potter’s tales (like many children’s stories) begin centrifugally, with adventurous and naïve protagonists straying further from home, but never fully leaving its orbit. The Tale of Pigling Bland bucks certain trends: notably, the title character (unlike Peter, Jeremy, Jemimah, and Tom) avoids being eaten and escapes peril with his human outfit intact: he and Pig-wig, a “perfectly lovely” new friend who was also being fattened up in the farmer’s house, escape (though they piggily wait to be fed supper before absconding). Together they cross the county line, a border past which they are seemingly outside the reach of the law and the meat trade. That they are homeless and penniless doesn’t seem a concern; they sing and jig, celebrating their future together. It is as if the county line they traversed marks the border out of Potter’s fabular universe in which dressing for dinner labels certain characters as a potential main course.

Gabriel Fried is the author of two poetry collections, The Children Are Reading and Making the New Lamb Take, and the editor of an anthology, Heart of the Order: Baseball Poems. He teaches in the creative writing program at the University of Missouri and is the longtime poetry editor for Persea Books.

Comments are closed.